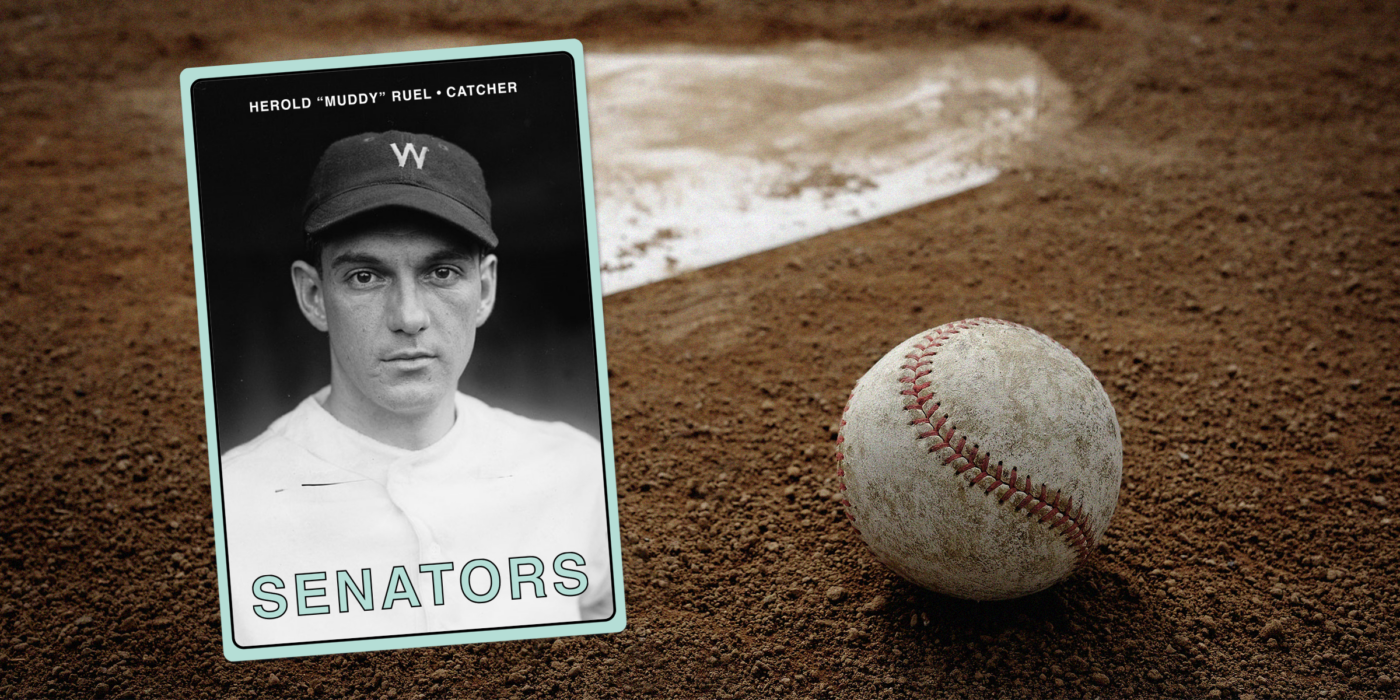

A hundred years ago this month, one of Major League Baseball’s smartest players had to figure out how to get out of a seven-game batting slump with a World Series title on the line. But he had his intellect going for him. The man in the batter’s box at the game’s most pivotal point was also a lawyer who had received his legal training at Washington University.

Here is his story:

On Oct. 10, 1924, in the bottom of the 8th inning of Game 7 of the 1924 World Series, Ruel, the starting catcher for the Washington Senators, came up to bat with his team trailing 3-1 to the New York Giants.

With a man on second base, Ruel, who had been 0-18 in the series, represented the potential tying run. A lot of managers would have opted for a pinch-hitter, looking for a more muscular batter to hit a game-tying homer — not to mention to replace someone in a series-long slump. Ruel was about the worst candidate to tie the game with one swing; he hadn’t homered since 1921. But he was a decent hitter, batting .283 that season. Washington player-manager Bucky Harris was confident “that little Muddy Ruel would come through when most needed,” as he said later.

Indeed, “little Muddy Ruel” — he was listed at 5 feet 9 inches and 150 pounds, although some pegged him at 140 — delivered in a big way, beating out an infield hit and advancing a runner to third base. The next man up walked, and Ruel wound up scoring the tying run on a hit by his manager, Harris, setting the scene for an extra-inning classic at old Griffith Stadium in the nation’s capital.

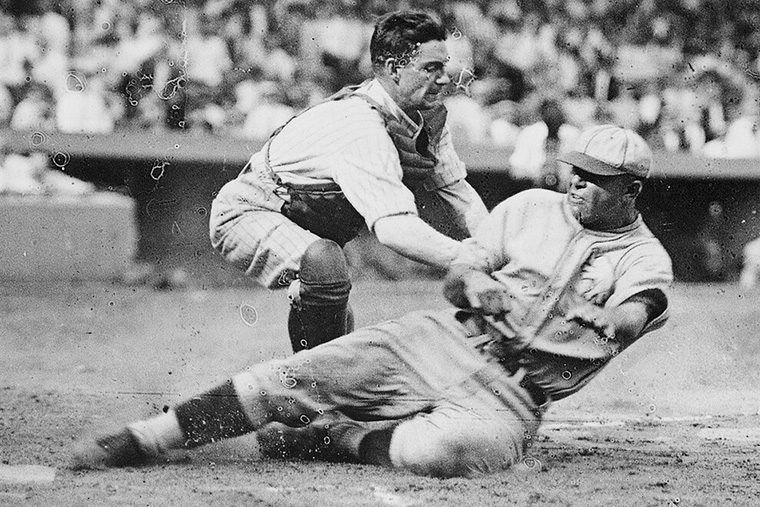

When Ruel came up in the 12th inning with one out, he popped a foul behind home plate, but the baseball gods sided with him again. Catcher Hank Gowdy tripped over his mask, stumbled and muffed the play, giving Ruel another shot. “Like a sinner forgiven,” as he later described his chance for redemption, Ruel drilled a ball down the left-field line for a double. Two batters later, he came flying home on the series-winning hit by Earl McNeely, leading to pandemonium in the old ballpark. (The ensuing madness is captured in this Library of Congress film.)

The championship capped off one of the most improbable storylines in baseball history. The Senators, fourth-place finishers the year before, dethroned the three-time defending American League champion New York Yankees to win the 1924 pennant, before beating the heavily favored Giants in the World Series. It was the first — and last — World Series title for the Senators. Washington wouldn’t win another baseball title for 95 years, when the Washington Nationals beat the Houston Astros in 2019.

An expert on baseball and law

Ruel was born in St. Louis in 1896, learned baseball on the city’s sandlot fields and made his debut with the St. Louis Browns at age 19 in 1915.

He played one year for the Browns before then-General Manager Branch Rickey, himself a lawyer, cut Ruel loose but not before advising him to finish his education. He enrolled at Washington University School of Law in 1917, admitted as a “special student” that allowed him to attend classes during the offseason, which he did for five years while playing with the Yankees and later the Red Sox. Known as the rare intellectual in professional baseball, he took the Missouri Bar exam on Dec. 20, 1922, and was admitted on Jan. 3, 1923. Later, in 1929, Ruel was admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court while still playing baseball.

New York Times baseball columnist Arthur Daley called Ruel “an aristocrat among ball players during an era when there were mighty few aristocrats in their ranks. He dressed with a quiet elegance. He spoke in quiet, scholarly tones and behaved with a quiet propriety … He even was accused of the unthinkable crime of smuggling books of Shakespeare into his room.” Ironically — or perhaps fittingly, depending on your point of view — Ruel is the player who came up with the phrase “tools of ignorance” to describe the catcher’s protective gear.

Ruel was also one of the best defensive catchers of his era, throwing out 45 percent of opposing base-stealing attempts. But he had some good offensive seasons, too, including a career year in 1927 with the Senators, when he hit .308 with a .403 on-base percentage and finished sixth in the MVP vote.

Ruel never did become a practicing lawyer, but he became an expert on baseball law, which led to an appointment as assistant to Major League Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler in 1945 and 1946. Chandler had gotten off on the wrong foot with the owners, in part by advocating pay raises for umpires. As legendary baseball writer Red Smith wrote, “When the club owners discovered they had bought a turkey when they chose Happy Chandler for Commissioner, it was to counselor Ruel that they turned for rescue.”

Ruel ended up playing 19 seasons for eight different teams. Afterward, in addition to his stint in the commissioner’s office, Ruel spent time as a coach for the Chicago White Sox and Cleveland Indians; a manager for one season for the St. Louis Browns; and a general manager for the Detroit Tigers.

Ultimately, the former WashU law student was known in baseball for two things: the Senator’s only World Series title and his intelligence behind the plate, including helping to revive the legendary Walter Johnson’s career. In Ruel’s second season in Washington, which culminated with that ’24 World Series title, Johnson had an MVP season, his best in years at age 36, leading the league in wins (23), ERA (2.72), strikeouts (158) and shutouts (6).

“Muddy was the smartest catcher I ever had,” Johnson said. “He took hold of me when I was through and made a pitcher out of me again.”

Frederic J. Frommer, AB ’89, a writer and sports and politics historian, is the author of several books, including You Gotta Have Heart: Washington Baseball from Walter Johnson to the 2019 World Series Champion Nationals.