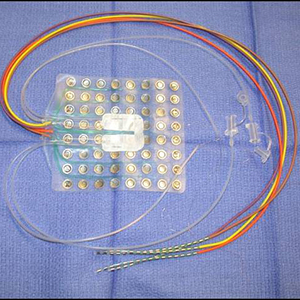

Surgeons at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are testing the ability of this cooling grid to reduce seizures that cannot be controlled through medication or surgery. In a separate study, the surgeons and their collaborators at other universities showed that brain cooling reduced seizures in a rat model of epilepsy.

In the weeks, months and years after a severe head injury, patients often experience epileptic seizures that are difficult to control. A new study in rats suggests that gently cooling the brain after injury may prevent these seizures.

“Traumatic head injury is the leading cause of acquired epilepsy in young adults, and in many cases the seizures can’t be controlled with medication,” says Matthew Smyth, MD, associate professor of neurological surgery and of pediatrics at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “If we can confirm cooling’s effectiveness in human trials, this approach may give us a safe and relatively simple way to prevent epilepsy in these patients.”

Scientists at the University of Washington and the University of Minnesota, and surgeons at Washington University reported their findings in Annals of Neurology.

Cooling the brain to protect it from injury is not a new concept. Cooling slows down the metabolic activity of nerve cells, and scientists think this may make it easier for brain cells to survive the stresses of an injury.

Doctors currently cool infants whose brains may have had inadequate access to blood or oxygen during birth. They also cool some heart attack patients to reduce peripheral brain damage when the heart stops beating.

Smyth and his collaborators have been exploring the possibility of using cooling to prevent seizures or reduce their severity.

“Warmer brain cells seem to be more electrically active, and that may increase the likelihood of abnormal electrical discharges that can coalesce to form a seizure,” Smyth says. “Cooling should have the opposite effect.”

Raimondo D’Ambrosio, PhD, an associate professor of neurosurgery at the University of Washington, has developed a rat model of post-traumatic seizures. The rats develop chronic seizures weeks after a brain injury.

D’Ambrosio, John Miller, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at the University of Washington, and Steven M. Rothman, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Minnesota, tested a headset that cools the brain on the rat model. They were originally studying the headset’s ability to stop seizures when they noticed that cooling seemed to be not only stopping but also preventing seizures.

Scientists redesigned the study to focus on prevention. Under the new protocols, they put headsets on some of the rats that cooled their brains by less than 4 degrees Fahrenheit. Another group of rats wore headsets that did nothing. Scientists who were unaware of which rats they were observing monitored them for seizures during treatment and after the headsets were removed.

Rats that wore the inactive headset had progressively longer and more severe seizures weeks after the injury, but rats whose brains had been cooled only experienced a few very brief seizures as long as four months after injury.

Brain injury also tends to reduce cell activity at the site of the trauma, but the cooling headsets restored the normal activity levels of these cells.

The study is the first to reduce injury-related seizures without drugs, according to Smyth, who is director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery program at St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

“Our results show that the brain changes that cause this type of epilepsy happen in the days and weeks after injury, not at the moment of injury or when the symptoms of epilepsy begin,” says Smyth. “If clinical trials confirm that cooling has similar effects in humans, it could change the way we treat patients with head injuries, and for the first time reduce the chance of developing epilepsy after brain injury.”

The researchers have been testing cooling devices in humans in the operating room, and are planning a multi-institutional trial of an implanted focal brain cooling device to evaluate the efficacy of cooling on established seizures.

This research was

supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute

of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS053928, R.D.; NS042936, S.M.R.;

EB007362, F.D.), CURE (5154001.01, R.D.; 5154001.05, M.D.S.); the U.S.

Army Medical Research and Material Command; and the University of

Washington.

D’Ambrosio R, Eastman CL, Darvas

F, Fender JS, Verley DR, Farin FM, Wilkerson H-W, Temkin NR, Miller JW,

Ojemann J, Rothman SM, Smyth MD. Mild passive focal cooling prevents

epileptic seizures after head injury in rats. Annals of Neurology, DOI:

10.1002/ana.23764.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.