Muschamp, et al.

Muschamp, et al.

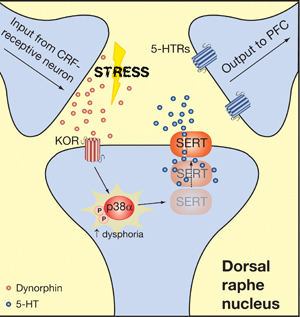

Stress exposure activates kappa-opioid receptors on neurons, which, in turn, activate the p38 protein, limiting available serotonin. Image Copyright Neuron, vol. 71 (3). Used with permission.

Researchers studying mice are getting closer to understanding how stress affects mood and motivation for drugs.

According to the researchers, blocking the stress cascade in brain cells may help reduce the effects of stress, which can include anxiety, depression and the pursuit of addictive drugs.

A research team from St. Louis and Seattle reports in the Aug. 11 issue of the journal Neuron that in mice exposed to stress, a protein called p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) influences the animal’s behavior, contributing to depression-like symptoms and risk for addiction.

The first author is Michael R. Bruchas, PhD, assistant professor of anesthesiology and of anatomy and neurobiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and the senior investigator is Charles Chavkin, PhD, professor of pharmacology at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The researchers demonstrate that p38α MAPK protein is activated by kappa-opioid receptors on neurons to regulate serotonin, a key neurotransmitter that helps regulate mood. When exposed to stress, the brain releases hormones that specifically interact with kappa-opioid receptors on neurons. Those receptors, in turn, activate p38α MAPK, which then interacts with the serotonin transporter in the cells to reduce the amount of available serotonin.

In this study, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the researchers looked at a brain region, called the dorsal raphe nucleus, where many stress-related factors and serotonin converge. They found that after stress exposure, mouse brains activate p38α MAPK, lowering serotonin levels and triggering depression-like behavior as well as drug-seeking behavior in the mice.

Stressed animals withdrew and did not interact with other mice. In animals that had been given cocaine injections while in specific places in their cages, stress made them more likely to physically seek out those locations where they had received the drug.

“We call these responses ‘depression-like’ and ‘addiction-like’ behaviors because we can’t ask mice if they’re addicted or sad,” Bruchas says. “But just as depressed people often withdraw from social interactions, stressed mice do the same thing. We also observed that stressed mice return more often to the place where they received cocaine.”

Next, investigators used a relatively novel genetic technology to disable the p38α MAPK protein only in cells of the brain’s serotonin system. Without the p38α protein, the stress-exposed mice no longer withdrew from social interactions, displayed depression-like behavior or sought drugs.

While working in Chavkin’s laboratory at the University of Washington, Bruchas and his colleagues studied mice exposed to what they call social defeat stress.

“We put a mouse into an enclosure with an ‘aggressor’ mouse,” Bruchas says. “Some mice, like some humans, are more dominant and aggressive. When a non-aggressive mouse is put into a cage with an aggressive animal, that aggression causes stress similar to what we might see in an adult human working for a difficult boss or a teenager who has to deal with a bully at school.”

Just as interacting with a “bully” mouse is similar to dealing with stressful environments, Bruchas and Chavkin say the cascade of events in the brain that contributes to serotonin reduction appears to be similar in both mice and humans.

“When people take antidepressant drugs called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, to relieve depression, the drugs act on a cellular pump called the serotonin transporter, and this results in more serotonin in the brain,” Bruchas says. “We think that the involvement of the p38α protein and kappa-opioid receptors represents an important finding in figuring out how it is that cells regulate depressive and addictive behaviors.”

In his new laboratory at Washington University, Bruchas says he plans to test whether the same p38α MAPK protein is involved when the drug is nicotine or amphetamine.

“It will be important to determine whether this pathway is conserved for drugs of abuse other than cocaine,” he says. “If so it will further highlight the importance of working with chemists to target this pathway for potential therapies.”

Bruchas also plans to look at other brain areas to learn whether similar responses are occurring in response to stress.

Meanwhile, in Seattle, Chavkin’s group continues to examine stress effects on addiction, long-term addiction models and whether humans regulate stress through the same kappa-opioid/p38α pathway.

“Our data demonstrate that p38α is required for local regulatory control of serotonin transport, which ultimately controls behavioral responses, including social avoidance and relapse of drug-seeking,” Chavkin says. “These results are important because they highlight novel therapeutic targets to promote stress resilience.”

Bruchas MR, Schindler AG, Shankar H, Messinger DI, Miyatake M, Land BB, Lemos JC, Hagan C, Neumaier JF, Quintana A, Palmiter RD, Chavkin C. Selective p38α MAPK deletion in seretonergic neurons produces produces stress-resilience in models of depression and addiction. Neuron, vol. 71 (3), Aug. 11, 2011. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.011

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Hope for Depression Research Foundation.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.