Cats have fascinated and intrigued artists throughout the ages, as evidenced by paintings on the inside of pyramid walls from ancient Egypt, oil masterpieces from the Renaissance period and, of course, today’s cat videos and memes. Over the last several decades, scientists have also turned their gaze to cats, studying Felis catus in much the same way that they study lizards, birds, elephants and other animals.

Biologist Jonathan Losos, the William H. Danforth Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis and director of the Living Earth Collaborative, is teaching a new course at WashU that takes advantage of this interest, encouraging biology majors to get to know one of the most popular pets in America.

“I think one of the appeals to people of having a cat is that it’s your own little piece of the wild,” Losos said. “You’ve got a mini-lion in your house. Cats are not that much changed from their wild ancestors.”

The owners of the 58 million pet cats in the U.S. know exactly what he means.

Losos himself is a cat lover — he currently has four — and he fondly remembers his first pet cat from when he was 5 years old. But he didn’t consider cats scientifically interesting until relatively recently. About 10 years ago, Losos watched a BBC documentary that followed a town’s efforts to study the cats in their community, using modern research tools like GPS collars. At about the same time, Losos read a book by John Bradshaw called “Cat Sense.”

“It clued me in that there is actually lots of interesting research about domestic cats, and that people are studying them in the same ways that I and my colleagues study lizards and other species,” Losos said. “Radio tracking, genome studies, community ecosystem studies: the same sorts of questions and the same tools! And that surprised me.”

WashU seniors in “The Science of Cats” course take what they have learned about evolutionary biology, ecology and behavior and apply it to an organism that they care about. They consider: Where did house cats come from? In what ways, if at all, are house cats domesticated? What impacts do cats have on the environment?

“As an evolutionary biologist, an interesting question is the extent to which we have been able to shape cats through a process of selection — in this case, artificial selection,” Losos said. “Cats show us the power of selection to lead to rapid evolutionary change.”

Most of the domestic cat breeds that we recognize today originated within the last 150 years. But they often don’t seem very different from one another, especially when compared with dog breeds. Many breeds of cat are only different in their “paint jobs” — that is, the color, pattern, length and texture of their coats.

This is changing, though: Enter the munchkin cat, for example, whose stubby legs put it on the same level as a kind of feline dachshund. Or the lykoi or “werewolf cat,” which gets its curious and shaggy appearance as the result of a single genetic mutation, as Losos noted.

“Some are quite distinctive,” Losos said. “The extremely short muzzle of Persian cats or the long tapered one of modern Siamese are unlike any species of feline that has evolved in the family’s 20-million-year history.”

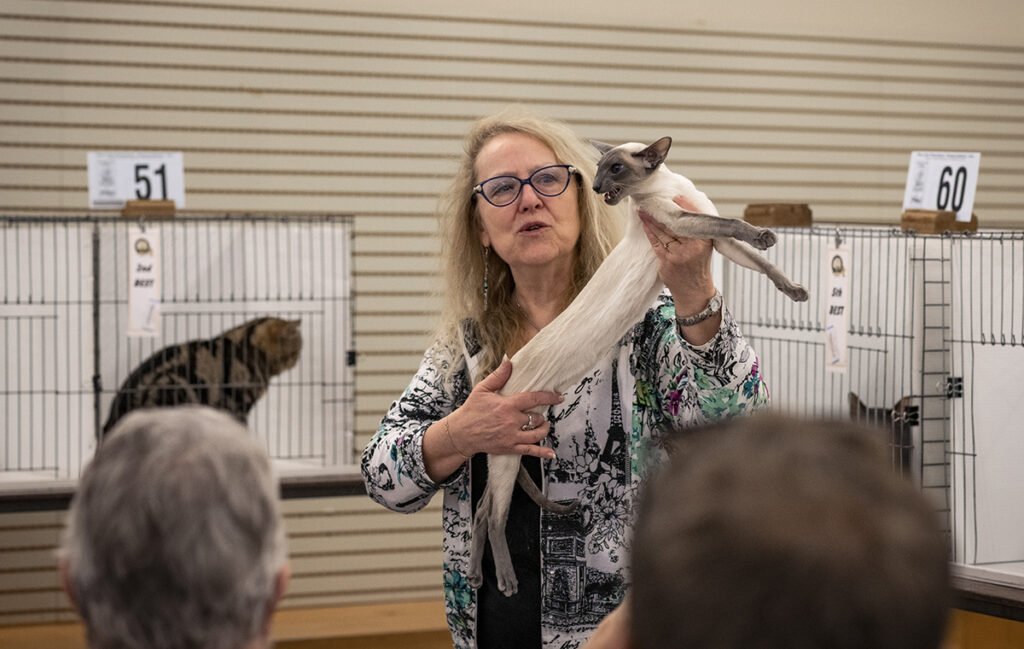

To explore some of this diversity, Losos and his students took a field trip to the Illini Cat Club and Grassroots Cat Fanciers show in Champaign, Ill.

Losos warned students to set aside any expectations they might have about cat shows based on televised dog shows like Westminster.

“You can’t run them around a ring,” Losos said.

“I was shocked by the seriousness of the cat owners and the judges,” said Logan Lacy, a senior biology major who attended the show. “Without knowing what’s going on, it appears like a random well-dressed person is just playing with cats with a feather or a ball on a stick. But in reality, these people are judging them on a very specific set of criteria that each breed is supposed to have, and most of the owners spend hours grooming and taking care of their cats.”

“I thought the cat show was very cool! It was a little smaller than I first expected, but being there really allowed the class to immerse themselves in a huge community of passionate cat people,” said Sam Cohen, another senior biology major.

“Being at the cat show definitely helped in that we were able to see the different breeds of cats and how artificial selection affected them,” Cohen said. “I work in a veterinary clinic and rarely see some of the breeds I saw at that cat show. A lot of them are really rare.”

“The Science of Cats” also does not shy away from more contentious topics related to cats. Students also visit a local no-kill shelter and read papers that document the impacts of feral cats on fragile island ecosystems like those in Australia, where there are no native wild cats.

In addition to leading this new course, Losos has written a book for popular audiences, “The Cat’s Meow: How Cats Evolved from the Savanna to Your Sofa.” In the book, coming out in May from Penguin Random House, Losos describes how the domestic cat has, from its origins in Africa, been transformed in comparatively little time into one of the most successful species on the planet.

That process of domestication itself is a topic of great debate.

“There’s a lot of different definitions,” Losos said. “But one key aspect of domestication is how different an animal is from its wild ancestor.”

Dogs, for example, differ from their ancestors in appearance and behavior. “They do things that wolves do not do,” Losos said. But with cats, it’s not that straightforward.

“There are some differences, but not very many, and they’re not very substantial,” Losos said. “And — as we are all aware — house cats will readily revert to a wild state.”