Threads of Change

Can fashion change our world for the better?

Each year, bold and beautiful fashion designs are showcased around the world—on runways, online and in print. Great fashion design makes us look better…but can it help us be better? At Washington University in St. Louis, students are not only exploring how fashion changes us, but also how it just might change the world.

From adaptive clothing for people with disabilities to expressions of one’s culture to garments made of recycled textiles, here’s how fashion is threading its way into the future.

Functional fashion for all

In recent years, fashion brands have become more aware of accessibility needs, with companies like ASOS, Tommy Hilfiger, and Target providing options for people with disabilities. But according to an article in Forbes, big retailers and fashion houses don’t always get it right, neglecting the people they purport to serve in the design process.

At WashU, there are a number of initiatives to make the fashion process more inclusive.

In the fall of 2021, the “Made to Model” program, was founded by WashU students with the hopes of producing, designing, and creating adaptive formal wear for St. Louis-area kids with functional disabilities who may otherwise be overlooked.

When I first tried it on, I felt like a princess. It’s really cool that I get to be in a fashion show for the first time.

Ella Schaflluetzel, Made To Model fashion show model

Nine months later, that vision came to life at the Sam Fox School’s 93rd Annual Fashion Design Show on WashU’s campus. The kids took to the runway, modeling their outfits before an appreciative crowd.

This is not the first time WashU students came together to meet the needs of people with disabilities. In 2017, they designed prototype garments for rugby athletes who use wheelchairs.

With the help of faculty from the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, the McKelvey School of Engineering and the School of Medicine’s Program in Occupational Therapy, these students researched, designed and constructed prototype garments specifically tailored to the needs of athletes with disabilities. Modifications included mesh fabrics to improve ventilation and extra-wide pant legs to facilitate dressing.

By making fashion accessible to all, more individuals are able to access and appreciate its unique uses and power of expression. “What they’re doing with trying to install the cooling systems into the fabric can help a lot of people,” says Clayton Braun, a gold medal-winning defender for the St. Louis Spartans wheelchair rugby team. “There’s nothing really specific for us out there. A lot of times, we’re finding things, modifying them and making our own.”

Celebrating culture, making meaning

Clothing also can be used to highlight culture and identity. At fashion shows and cultural celebrations, people show off traditional outfits and find ways to connect with their roots and heritage.

“Almost all of us go through a phase in life where we’re denying our culture,” says Ishana Tata, an undergraduate student who organized the fashion show at WashU’s annual Diwali showcase. But now, wearing an Indian lehenga “gives me confidence, connects me back to my roots, and just makes me feel happy.”

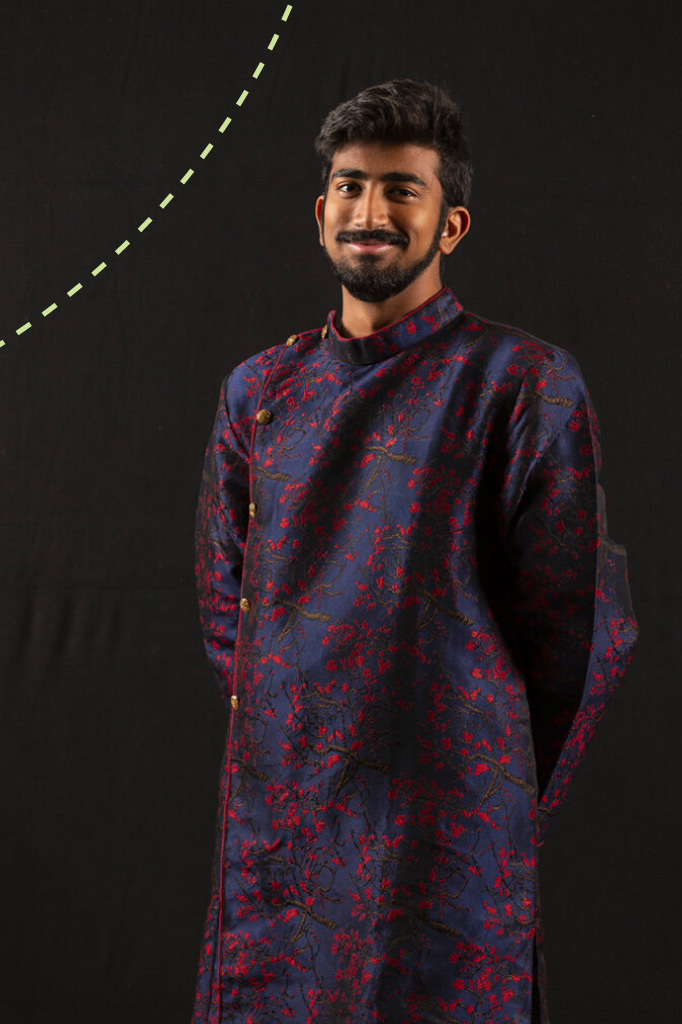

Senior Ishana Tata, the fashion show coordinator, and first-year student Anirudh Jaishankar model their outfits for the Diwali fashion show. Tata is wearing a lehenga with intricate beadwork that she purchased in New Delhi. Jaishankar is wearing a kurta with ornate patterns. Because Diwali coincides with the Hindu New Year, wearing new clothes signifies a new beginning, according to Jaishankar.

The African Student Association at WashU hosts an annual fashion show with dance performances, live music, a flag walk and more. First-year student Lina Abdo wore an off-the-shoulder kemis, a dress typically worn to weddings and parties.

Sophomore Hieran Andeberhan wore a traditional Saho dress from Eritrea. “This dress belongs to a family friend, and I chose it with my mother’s encouragement to be more inclusive and representative of the diverse tribal clothings found in Eritrea,” says Andeberhan.

A student wears a Korean chibok while performing in the Samulnori act at the university’s Lunar New Year Festival showcase in 2022. Samulnori was performed by and for the common people in Ancient Korea, often to celebrate a harvest. The white top and bottom represent clothing worn by farmers, and the colorful ribbons have specific meanings: the blue symbolizes the sky, red symbolizes the ground, and yellow symbolizes humans, or the farmers who occupy the space between the sky and ground.

The environmental impact of fashion

While fashion is a meaningful way for people to express aspects of their identity, choices made within the industry have a big impact on the planet.

An estimated 95 percent of retail clothing is recyclable, but the vast majority ends up in landfills — more than 20 billion pounds annually in the United States alone.

Mary Ruppert-Stroescu, associate professor and fashion design area coordinator in WashU’s Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, is tackling this issue. Ruppert-Stroescu developed — and patented — an integrated process designed to help clothing manufacturers create new apparel from recycled fabric.

“In fashion, sustainability is a buzzword,” she says. “But a real commitment to zero waste? That’s still pretty rare.” Watch the video below to see what Ruppert-Stroescu is doing to change that, and then read more about how she is reimagining a different future for textile production.

Christine Ekenga, a former faculty member in WashU’s Brown School who is now at Emory University, researches fast fashion. “From the growth of water-intensive cotton, to the release of untreated dyes into local water sources, to workers’ low wages and poor working conditions,” says Ekenga, “the environmental and social costs involved in textile manufacturing are widespread.”

How widespread?

A 2018 study by Environmental Health found that 80 billion pieces of clothing are purchased each year, at a cost of $1.2 trillion.

To manufacture 2 pounds of textiles requires 53 gallons of water.

The average American gets rid of 80 pounds of clothing each year and over 65 percent of that ends up in landfills.

During Fashion Revolution’s 2021 Fashion Revolution Week, it emerged that 200 million trees are felled each year to make cellulosic fabrics, 35-40% of those coming from old growth woodlands.

A 2019 report by the United Kingdom’s Environmental Audit Committee found that 15% of all clothing fabric is wasted at the cutting stage of production — before it even has a chance to get into stores.

Each time a piece of clothing is washed and dried, microfilaments are shed that move through sewage systems and end up in waterways. The group Earth.org estimates that a half-million of these contaminants reach the ocean each year.

The future of sustainable fashion

To address the negative impacts of the fashion industry, many have turned to alternate shopping models.

Thrifting, or shopping at thrift stores, second-hand shops, garage sales and flea markets, has gained popularity among younger generations in recent years. According to the 2022 Resale Report published by online thrift store thredUP, the secondhand market in the United States was worth $35 billion in 2021 and is expected to more than double by 2026, reaching $82 billion.

Circular fashion and the closed-loop system are also on the rise. In this approach, clothing is used for as long as possible — then repurposed into something new. Clothing is designed with purpose, longevity, resource efficiency, biodegradability and recyclability in mind. Companies like For Days and Reformation have programs that allow consumers to recycle old clothing for store credit.

Saylor, a fashion company founded by WashU alum Jillian Shatken, also allows customers to sell their pre-owned Saylor garments and earn money towards future purchases. The company, which aims to empower women, create eco-friendly designs and serve as a good community partner, offsets 100% of carbon emissions from orders and uses biodegradable, compostable, and/or recycled materials for its hang tags, labels, and packaging.

Even donated clothing can reach the end of its life cycle. When that happens, it may end up in landfills. But WashU students are making decisions that repurpose second-hand fashion. At the “Fashion’s Afterlife: Trends to Trash and Back Again!” event hosted by Fashion Group International St. Louis, WashU undergraduate students Bei Qi, Emily Carlin, and Indigo Amunategui showed off their work.

Indigo Amunategui, a sophomore, used materials from Found by the Pound, a thrift store in Berkeley, Mo., to create a garment that spoke to the future of fashion and sustainability. Amunategui chose T-shirts because “everybody wears them and there are so many of them in landfills across the world.”

“My goal was to create a garment that embraced the ‘foundness’ of the materials,” said Amunategui. “The different colors, the different fabrics, whatever text was on the shirts, holes, tears and even stickers. I had a plan for the dress, but let the material guide me when it came to the final shape and length of the dress.”

A student models Amunategui’s design, made of second-hand T-shirts, at the “Fashion’s Afterlife: Trends to Trash and Back Again!” event. (Courtesy photo)

A student models Qi’s design, made of second-hand scarves, at the “Fashion’s Afterlife: Trends to Trash and Back Again!” event. (Courtesy photo)

Bei Qi, a sophomore, designed a Technicolor Cape from 16 second-hand scarves. “I like the idea that designers can take the same old garment and transform it in a multitude of innovative ways based on different concepts; the endless possibilities are exciting and inviting,” Qi said. “I view fashion as a malleable medium that never dies. It has the wonderful ability to take on new forms and contexts through reinvention and reconstruction of old materials, bringing them into a different world as opposed to completely starting from scratch.”

At WashU, Sharing With a Purpose (SWAP) is a student-run reuse and exchange store grounded in sustainability, justice, self-determination, and cooperation. Says alum Julia Ho, SWAP’s co-founder, “[It’s a place for] people in the community, faculty, workers, and students within and outside WashU to meet their everyday needs, share resources, and show solidarity with one another.”

Students organize clothes at the student-run reuse and exchange store SWAP. (Instagram)

SWAP hosts pop-up shops in locations around campus throughout the year. (Instagram)

More sustainable options begin in the design stages, too.

WashU alum Anastasia White is the founder and creative director of crescent bleu, a sustainable swimwear company. Her vision of sustainability is people-centered. To that end, crescent bleu offers a sustainable lifestyle to the people making the products. White also aims to expand her community involvement. “I make sure that my platform upholds companies and organizations that have like values,” she said. “For example, there are a lot of organizations currently promoting water safety and swim lessons in the Black community. I would love for the brand to be able to materially support those sorts of efforts.”

Similarly, WashU alum Paul Dillinger, Head of Global Product Innovation for Levi Strauss & Co., has advocated for the importance of sustainability in the design process. He designed Wellthread, a line of premium khakis, T-shirts and jackets made with easily-recyclable fibers, energy-conserving dyes, and reinforced components for extra durability. They are exclusively manufactured in factories that support programs to improve workers’ lives by investing in community development projects. Dillinger believes that durability is the most important sustainability feature. Accordingly, as the Louis D. Beaumont Artist-in-Residence in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, he had his students run their items through the washer and dryer to see how they held up with regular wear and tear.

Fashion is more than just the clothes we wear — it is a way to make a tangible impact, either positive or negative, on the world around us. The next time you’re looking at the beautiful designs worn at fashion shows and galas, or even making a decision about your next pair of jeans, consider the ways in which mere cloth and thread impact our future: bringing people together and working toward a more sustainable planet.

Producers: Amanda Young, Ariella Zagorsky

Authors: Leslie McCarthy, Amanda Young, Ariella Zagorsky

Designers: Brandy Rustemeyer, Kayse Larkin, Amanda Young

Animator: Javier Ventura

Videographers: James Byard, Tom Malkowicz

Photographers: Carol Green, Devon Hill, Sid Hastings, Jerry Naunheim Jr., Cameron Thompson, Jiyoon Kang, Whitney Curtis, Max Morse

Contributors: Kristin Grupas, Anne Cleary, Liam Otten, Cassaundra Moore, Kia Holt, Kristen Gau

Editor: Ryan Rhea