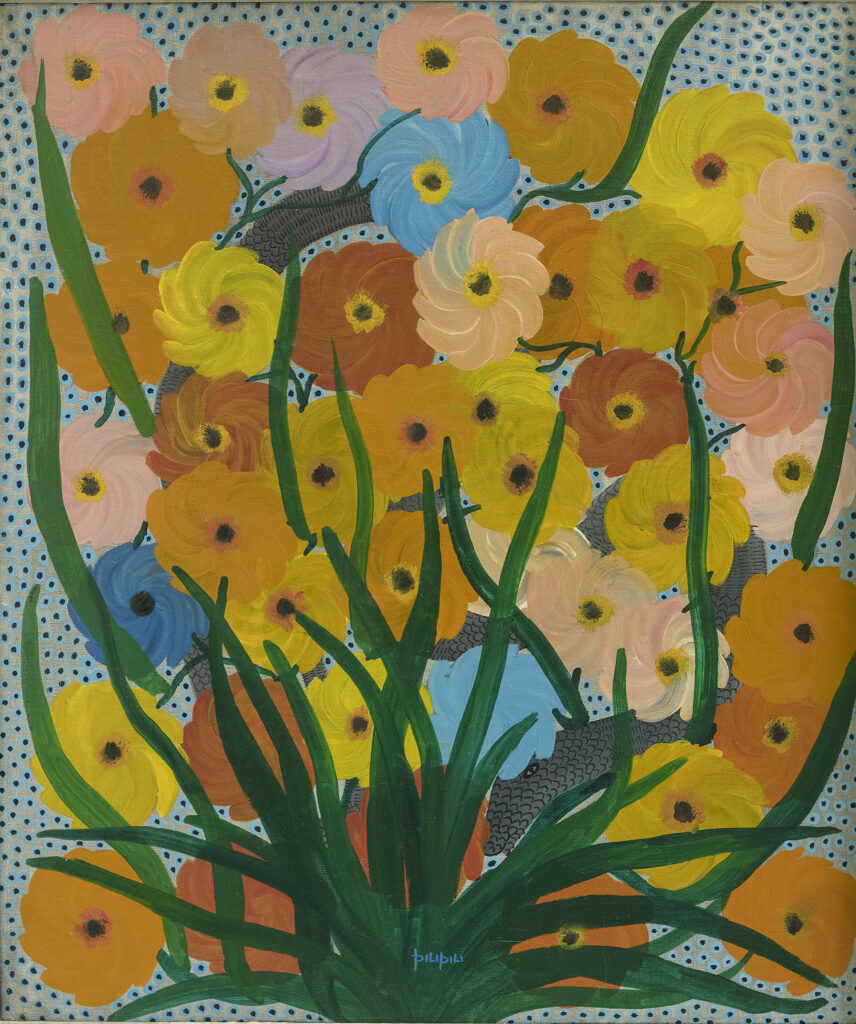

Flowers erupt against a pointillist backdrop. Thin green vines twist and rise through swirling strokes of blue and pink, orange and umber. A gray serpent lurks patiently below. In “Snake Amid Flowers,” Congolese painter Pilipili Mulongoy (1914-2007) reflects the beauty and danger of the natural world as well as the optimism and unease of Africa’s independence period.

This spring, the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University in St. Louis will feature “Snake Amid Flowers” in “African Modernism in America.” Organized by the American Federation of Arts and Fisk University Galleries in Nashville, Tenn., the exhibition is the first traveling survey to explore both the diverse aesthetic strategies employed by African artists in the years after World War II and their complex relationships with American artists, scholars, patrons and cultural organizations.

“ ‘African Modernism in America’ draws out a very specific historical moment,” said Perrin M. Lathrop, assistant curator of African art at the Princeton University Art Museum, who co-curated the exhibition with Nikoo Paydar, former associate curator of the Fisk Galleries, and Jamaal Sheats, curator and director of the Fisk Galleries and associate provost of art and culture.

Between the late 1940s and late 1960s, a series of global shifts, including African decolonization and also the attempted decolonization, through the civil rights movement, of the United States, led artists to engage with a new politics of form, Lathrop explained. That is, artists “deliberately integrated different visual and cultural traditions, synthesizing what they’d learned from their own cultures with what they were seeing out in the world.”

The exhibition and accompanying catalog also reflect a rising scholarly cohort that is bringing new attention to the work of modern and contemporary African and African American artists. “Today, institutions are thinking about representation in much more serious ways,” Lathrop said. “There’s been a generational change.”

Pastoral and radical

Drawn primarily from the Fisk University collections, “African Modernism in America” surveys more than 70 artworks by 50 artists. It opens with an exploration of the Harmon Foundation, an American organization that, in the mid-20th century, was devoted to promoting art of the African diaspora (and which later bequeathed a large portion of its collection to Fisk).

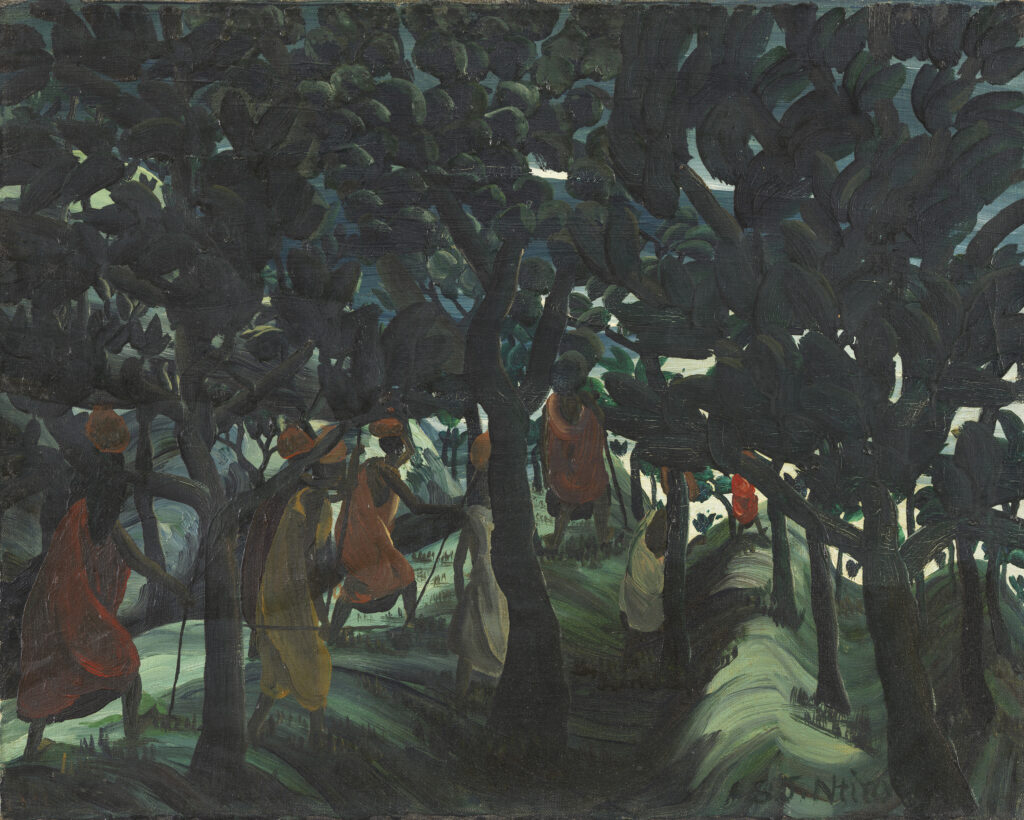

In 1960, the Harmon Foundation helped arrange for the Museum of Modern Art in New York to acquire “Men Taking Banana Beer to Bride by Night” (1956) by the Tanzania-born painter Sam Joseph Ntiro (1923-1993) — the first work by an African artist to enter MoMA’s permanent collection. With its muted palette and thick, almost-abstract brushstrokes, the painting is at once pastoral and radical, a traditional scene that also marks a hopeful vision for Tanzania’s coming independence.

The following year, Harmon organized the landmark exhibition “Art from Africa of Our Time,” which highlighted African art of the independence era. Upending Western expectations, which tended to view Africa as a unit rather than a conglomeration of distinct peoples, cultures, geographies and nations, the installation ranged from historical scenes by Nigerian painter (and political cartoonist) Akinọla Laṣekan (1916–1972) to gestural abstractions by Congolese painter Jean Luvwezo (b. 1938) to still lifes by Suzanna Ogunjami (c.1885-1952), an artist raised in Jamaica but who claimed Igbo descent.

Intersecting networks

“African Modernism” also reflects the continent-wide networks of artists, galleries, journals and education programs that supported postcolonial African artists. For example, both Demas Nwoko (b.1935) and Uche Okeke (1933-2016) studied at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology in Zaria, where faculty included Etso Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu (1921-1996). Notably, Nwoko and Okeke would exhibit together at the Mbari Artists and Writers Club in Ibadan, which later hosted an exhibition by Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) during the American artist’s first trip to Nigeria.

Other sections explore pan-African links between decolonization and the U.S. civil rights movement. For example, “Kumasi Market” (1962) by the American artist John Biggers (1924-2000) — a painting once owned by Maya Angelou — draws on his travels through Ghana in 1957, the same year that nation gained independence from Great Britain. David C. Driskell (1931-2020), longtime head of the Fisk University art department, is represented by “Yoruba Forms #5” (1969), a work that reflects his decades-long immersion in the history and symbolisms of African art.

Rounding out the exhibition is “The Politics of Selection” (2022), an immersive, three-part collage by contemporary Lagos-based sculptor Ndidi Dike. Building on her research into the Harmon Foundation at the Library of Congress in Washington and at Fisk University, the piece both explores and critiques the viewpoints, biases, prejudices, allegiances and omissions — particularly the erasure of women artists — that continue to shape how African art is seen and collected.

Visitor information

“African Modernism in America” will open at the Kemper Art Museum on Friday, March 10. Events will begin at 5:30 p.m. with a conversation between co-curators Perrin Lathrop and Jamaal Sheats and Bukky Gbadegesin, an associate professor of art history at Saint Louis University. A reception will immediately follow. The exhibition will remain on view through Aug. 6.

The Kemper Art Museum is located on Washington University’s Danforth Campus, near the intersection of Skinker and Lindell boulevards. Visitor parking is available in Washington University’s East End garage, which can be entered from Forsyth Boulevard or Forest Park Parkway.

Regular hours are 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Mondays and Wednesdays through Sundays. The museum is closed Tuesdays. For more information, call 314-935-4523 or visit kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu. Follow the museum on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Youtube.

Support

“African Modernism in America” is organized by the American Federation of Arts and Fisk University Galleries. Major support is provided by Monique Schoen Warshaw. Additional support is provided by grants from the Marlene and Spencer Hays Foundation, the Mellon Foundation and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.

The presentation at the Kemper Art Museum was made possible by the leadership support of the William T. Kemper Foundation. All exhibitions at the Kemper Art Museum are supported by members of the Director’s Circle, with major annual support provided by Emily and Teddy Greenspan and additional generous annual support from Michael Forman and Jennifer Rice, Julie Kemper Foyer, Joanne Gold and Andrew Stern, Ron and Pamela Mass, and Kim and Bruce Olson. Further support is provided by the Hortense Lewin Art Fund, the Ken and Nancy Kranzberg Fund, and members of the Kemper Art Museum.

Following its run at the Kemper Art Museum, “African Modernism in America” will travel to The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., in fall 2023 and to the Taft Museum of Art in Cincinnati in spring 2024.