In the 1930s, the photographer Ansel Adams struck up a friendship with California painter Chiura Obata. Yet the arrival of World War II would set these two celebrated artists on radically divergent paths — paths that would, in different ways, lead both to the now-infamous “war relocation centers” at which the U.S. government forcibly interred approximately 120,000 Japanese-Americans in the 1940s.

Soon, that path will converge again at Washington University when their sons, Michael Adams, M.D., and Gyo Obata, explore the impact of internment on their families in a public dialogue at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum.

Held in conjunction with the exhibit “A Challenge to Democracy: Ethnic Profiling of Japanese Americans During World War II,” the talk begins at 6 p.m. Oct. 2 in Steinberg Hall Auditorium. A reception will immediately follow.

“The first-person accounts of Michael and Gyo — along with those Japanese-Americans who were interned in the camps that we will hear from later in the semester — bring to life this tumultuous period in American history,” said Ira J. Kodner, M.D., director of the Center for the Study of Ethics & Human Values, which organized both events as part of the semester-long series “Ethnic Profiling: A Challenge to Democracy.”

“Events from this past summer — when grade-school children were ejected from a swimming pool in Philadelphia and Harvard professor (Henry Louis) Gates was arrested at his home — demonstrate the need for continued vigilance against ethnic and racial profiling in our own time,” Kodner said.

Michael Adams, an alumnus of the School of Medicine, was born and raised in the Yosemite Valley, site and subject of many of his father’s most famous photographs. There, his parents ran a small gallery, Best’s Studio, which also showed paintings and prints of the park by Chiura Obata. Both Ansel Adams and Chiura Obata taught summer classes through the gallery and often spent evenings together, sitting and talking over drinks.

“The Obata and Adams families were good friends long before the war,” Adams said. “The Obatas camped in Yosemite Valley each year, and we stored their camping equipment for them in our garage over the winter.”

Though just a child at the time, Michael Adams remembers summer visits by the teenage Gyo and his sister. “I am sure we all had meals together,” he said.

At the start of the war, Gyo Obata had just begun classes at the University of California, Berkeley, where his father taught painting.

However, to avoid internment, he transferred to Washington University’s School of Architecture, which, as an inland institution, was allowed to accept Japanese-American students.

“I left Berkeley the night before my whole family was interred,” Obata said. “Washington University was one of the few colleges that accepted Japanese-Americans.”

He said that had the telegram announcing his acceptance arrived one day later, “I’d have been sent to the camps, too.”

Instead, Obata finished his education in St. Louis. In 1955, he joined with fellow architecture alumni George Hellmuth and George Kassabaum to form Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum. The firm, which remains based in St. Louis, is among the largest in the world today.

The rest of the Obata family, unable to avoid internment, was sent first to the Tanforan detention center and then to the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah.

There, Chiura Obata made the best of a bad situation by establishing an art school.

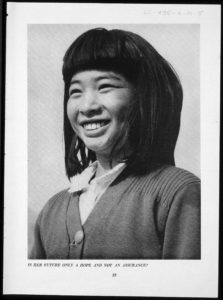

Meanwhile, Ansel Adams departed from his characteristic landscapes to document life in another of the camps — images he then collected in the book “Born Free and Equal: Photographs of the Loyal Japanese-Americans at Manzanar Relocation Center in Inyo County, California,” which he published in 1944.

“We, as citizens, can agitate for tolerance and fair play, but our agitation must be dynamic and persistent,” Adams wrote in his accompanying essay.

“It is easy for a ‘fair-weather lover of the Constitution’ to ‘favor’ tolerance, and mouth the principles of democracy, but it is quite another thing to stand up against opposition and fight for principles,” Adams wrote.

Several of Adams’ Manzanar photographs, along with paintings by Chiura Obata, will be featured in the “A Challenge to Democracy” exhibition, which opens immediately after the talk.

Jointly curated by Angela L. Miller, Ph.D., professor of art history and archaeology in Arts & Sciences, and doctoral students Elissa Weichbrodt and Anna Warbelow, the exhibit will explore the pervasive nature of ethnic profiling through a variety of visual records and materials.

The exhibition’s first section, “Profile of the Enemy,” consists of popular materials, including political cartoons, magazine covers and a government-issued handbook, that depict ethnically Japanese people as villainous.

By contrast, the second section, “Profile of the Patriot,” features images by Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Clem Albers and others who portrayed Japanese-Americans as loyal citizens.

The final section, “Resisting Profiles,” examines how Japanese-American artists, including Chiura Obata, Toyo Miyatake, Mine Okubo and Gene Sogioka, responded to their own internment — responses that ranged from subtle forms of resistance to outright protest.

Other events will include a lecture and slideshow by Michael Adams, titled “Ansel Adams: Photographs of Manzanar and the West,” at 2 p.m. Oct. 3 in the Kemper Art Museum.

Two performances of Rick Foster’s one-man-play “Dust Storm: Art and Survival in a Time of Paranoia,” which uses the art of Chiura Obata as background, will star actor Zachary Drake. The shows will begin at 8 p.m. Oct. 3 and at 4 p.m. Oct. 4 in Steinberg Hall.

Finally, Kimi Kodani Hill, Chiura’s granddaughter, will lecture on “The Art and Life of Chiura Obata” at 2 p.m. Oct. 4 in the Kemper Art Museum. Hill is the author of “Topaz Moon: Chiura Obata’s Art of the Internment.”

Copies will be available for sale in the museum bookshop, with a book-signing to follow.

All events are free and open to the public.

For more information about the ethnic profiling series, call 935-9358 or visit humanvalues.wustl.edu.