Neuroscientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a key difference in the way the brain functions in people who are depressed compared to those who are not.

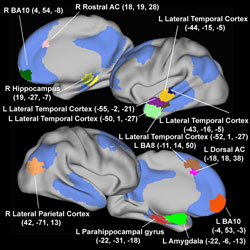

The study demonstrates that brain regions, collectively known as the default mode network, behave differently in depressed people. The default network typically is active when the mind wanders. It shuts down when an individual focuses on the job at hand. But the researchers found the network stays active in people who are depressed, even when they are concentrating on specific tasks.

The new work suggests individuals with depression may not be able to “lose themselves” in work, music, exercise or other activities that enable most healthy people to get “outside” of themselves.

“When healthy people engage in a very focused activity, they in a sense, lose themselves,” says senior investigator Marcus E. Raichle, M.D., whose research group in 2001 first identified the default mode network. “If you really are engaged in something, you kind of forget yourself, and that loss of self corresponds to the deactivation we observe in brain scans of the default network. But that doesn’t seem to happen in the brains of people with depression.”

Raichle, a professor of radiology, neurology, neurobiology, psychology and biomedical engineering, says one characteristic of the default network is that it tends to involve self-referential functions. For example, it may involve memories, not just memories of facts or information but about our own experiences and how they relate to that information — the difference between remembering that hijacked planes crashed into the World Trade Center on September 11 and remembering where you were when you watched or heard about the attack.

Brain regions in the default network assess what is going on inside of us, to survey the effects of the environment around us and to make judgments about whether or not we approve. Scientists have linked the network to inward-looking activities, a kind of internal narrative of our life stories.

The research team used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of 20 people with major depression as well as 21 individuals who were not depressed. None of the people in the study were being treated with antidepressant drugs at the time of their brain scans.

Once in the scanner, subjects were shown pictures designed to evoke emotion, from snarling dogs and violent scenes to pictures of flowers and smiling faces. Sometimes, study subjects simply reacted to the picture as they saw it. At other times, they were coached to regulate their responses. That is, if they saw a frightening picture of a snarling dog, they might remind themselves it was an imaginary scene or think to themselves that the dog was behind a fence and unable to hurt them.

Whether subjects simply reacted to the pictures or regulated their responses, brain regions in the default network became inactive as healthy participants looked at and responded to the pictures. Not so for those with depression.

“Some parts of the default network, such as the brain’s amygdala, are related to emotion,” says Yvette I. Sheline, M.D., professor of psychiatry and the study’s first author. “And emotional pictures made those regions more active in depressed people. Meanwhile, other structures that normally deactivate did not deactivate as much. They weren’t able to shut down in the same way as a normal person’s brain.”

Sheline says the depressed people in the study seemed to be more affected by the pictures than the healthy, control subjects. It was harder for them to detach the way people without depression could.

As she continues this research, Sheline now is looking at the brains of depressed people following treatment with antidepressant drugs. Preliminary results suggest that their default networks function more normally. She’s also planning to test cognitive behavior therapy to see whether it might help “reset” the brain’s default network in people with depression.

“People with depression often suffer from cognitive distortions,” Sheline says. “This is the thinking that leads from the idea that ‘I made a mistake’ to the notion that ‘I am a bad person.’ Cognitive behavior therapy gives people tools to fight against that kind of thinking and reorient themselves in ways that make them less vulnerable to depressive thoughts.”

The hope, she says, would be that treatment — either with medication or cognitive behavior therapy or both — might help deactivate overactive brain regions that keep depressed people embroiled in depressive thoughts and, in fact, reset the brain to function more normally.

“It’s as if the depressed brain has a cold,” Sheline explains. “We can take medication to treat cold symptoms, but we still have the cold until we get better. Drugs and therapy can improve the symptoms of depression, and this discovery may help us learn whether those therapies merely treat symptoms or whether they also improve the underlying disorder.”

The study was published in the Feb. 10 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sheline YI, Barch DM, Price JL, Rundle MM, Vaishnavi SN, Snyder AZ, Mintun MA, Sang S, Coalson RS, Raichle, ME. The default mode network and self-referential processes in depression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 106 (6), pp. 1942-1947, Feb. 10, 2009.

doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812686106

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.