Greet students by name. Avoid grading on a curve. Try not to schedule exams right after a break. A new guide from the Center for Teaching and Learning at Washington University in St. Louis offers instructors concrete ways to support students’ well-being without adding to their workload.

“Teaching is hard work, especially during a pandemic,” said Shaina Rowell, assistant director of educational development at the Center for Teaching and Learning. “But small changes in course design and in the classroom can have a big impact on student well-being. That matters now more than ever as a growing number of college students report mental health challenges.”

Rowell and mental health experts at the university’s Habif Health and Wellness Center have published “Promoting Student Well-Being in Learning Environments: A Guide for Instructors,” which draws upon University of Texas’ “Texas Well-being” guide and the latest research in both pedagogy and mental health. While it was written for Washington University faculty, the guide’s lessons are widely applicable.

Here, Rowell shares ways instructors can support student well-being in their teaching.

How do good teachers support student well-being?

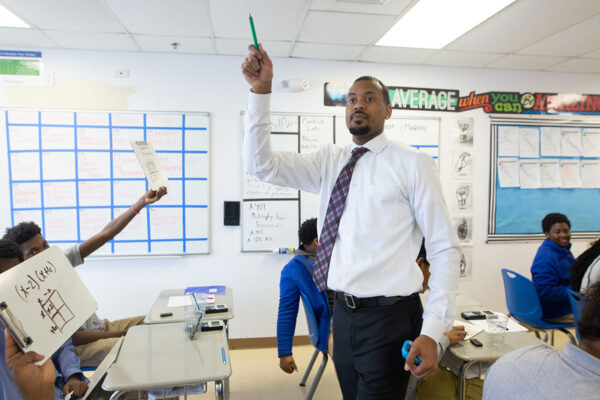

There are many ways to support student well-being. In this guide, we focus on four key areas: building social connection by creating a welcoming environment; demonstrating compassion by actively listening to students and employing policies that reduce stress; cultivating a growth mindset by showing students that mistakes are part of the learning process; and fostering a sense of gratitude by helping students appreciate positive experiences and find connection between their coursework and their purpose.

What does that look like in practice?

The guide breaks down different evidence-based strategies instructors can apply when designing their courses, building their syllabi and teaching in the classroom. Take, for instance, cultivating a growth mindset. When designing the class, think about ways to promote mastery and reward growth, like using low-stakes quizzes before giving high-stakes exams and creating opportunities for students to submit corrections on homework and tests. We also recommend not grading on a curve as it can create a toxic, competitive culture in the classroom and discourage students from working collaboratively. The guide also offers language instructors can use that normalizes struggle.

Teachers already carry so much on their shoulders. Will this contribute to their own stress?

This work does not need to be daunting. I expect a lot of instructors will read this guide and see that they are already putting into practice a lot of these ideas. We encourage instructors to think of the guidebook as a menu and pick one or two things to try in their own teaching — maybe it’s modeling gratitude by thanking a student for a good contribution in class or building social connections by having students go over homework in groups or by simply greeting them as they enter the classroom.

What is the difference between caring and coddling in the classroom?

Faculty can and should expect a high level of learning, but we can also acknowledge the difficulties students have and show them compassion. One step is to explicitly talk about your commitment to supporting student mental health and well-being. Another is to build flexibility into the structure of your course by, for instance, letting students know at the outset that they can turn in a total of two assignments up to 48 hours late. Caring for our students does not mean lowering standards.