Bugs.

We squish ’em, smash ’em, fear ’em, scare ’em, spray ’em, sweep ’em, flick ’em and generally misunderstand them.

But perhaps it’s time we rethink our relationship to our tiny, multi-legged invertebrate friends who have been around since long before we humans got here — and will be here long after we’re gone. Insects might be the most misunderstood inhabitants of our natural world, but there is much they can teach us, and there’s plenty of research going on to do just that.

Don’t smash that bug! What’s creepy-crawly to you and me is a treasure trove of information for scientists. From bomb-sniffing locusts to the social life of bees, scientists are gaining new insights into insects, arachnids and honeybees — including how our tiniest neighbors are solving some of the problems of our time (theirs, too).

Insects are …

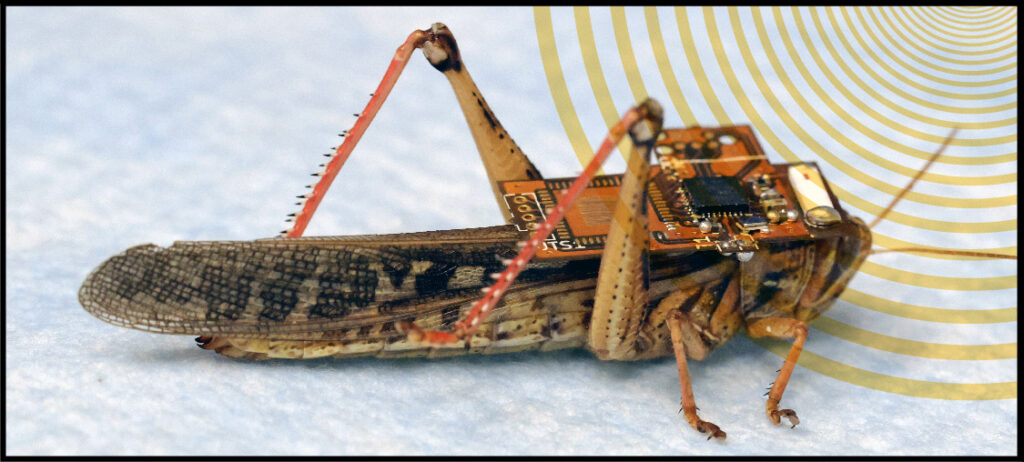

Bomb sniffing

Can locusts even smell explosives? Engineers in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis are working on it. They’ve already demonstrated the ability to control the locusts and the ability to read their brains, so to speak, to discern what it is they are smelling. And now, thanks to more new research, that question has been settled.

Waste disposing

The Black Soldier Fly is a bit of a superstar in sustainable agriculture but it’s also helping to break down organic waste. A company called Sanergy, co-founded by WashU alumnus Ani Vallabhaneni, is using Black Soldier Fly larvae to solve sanitation problems in Nairobi, Kenya.

“We’re closing the nutrient loop: We collect sanitation and other organic waste (kitchen and agricultural waste). We feed it to insects that convert it, and then we take the fertilizer to rural areas and put it back in the soil. We then sell the insects as animal feed.”

Ani Vallabhaneni

Team-working

An average hive can hold about 50,000 honey bees. But how do these essential pollinators know who their friends are? Biologists have discovered that honey bees rely on chemical cues, instead of genetic relatedness, to identify members of their colony. (And they have the stings to prove it … )

A hundred thousand visitors

About every 2-4 weeks, hundreds of thousands of visitors arrive on the Danforth Campus, and it’s the job of Michael Dyer and his team to welcome them.

Welcome them, then let them loose.

And it’s a good thing, too, as these visitors are instrumental in the critical research that goes on in the Department of Biology at WashU. Visitors such as Stratiolaelaps scimitus, a soil dwelling mite that feeds on fungus gnat larvae; or Amblyseius cucumeris, a natural predator of thrips, a microscopic species that can wipe out an entire plant. Throw in 5,000 lacewing cards and 25 million sprayable scanmasks, among other natural mites, worms and small wasps, and you’ve got quite the party of beneficial insects that allow the experiments of the Jeanette Goldfarb Plant Growth Facility to thrive.

Dyer is supervisor of the greenhouses in a 10,000-square foot on-campus facility for experimental plant growth and research among plant scientists. For more than 30 years, it’s been Dyer’s job to maintain the facility 24/7, 365 days a year –a virtual “plant whisperer.”

For a deep dive into the the Goldfarb greenhouses, including a few time-lapse videos of life inside this thriving metropolis, visit WashU’s Arts & Sciences at the link below.

Producer: Kristin Grupas

Writer/Editor: Leslie McCarthy

Multimedia producer: Anne Cleary

Animation: Javier Ventura

Video production: Tom Malkowicz

Visual design: Jennifer Wessler

Web design: Brandy Rustemeyer

Contributors: Talia Ogliore, Brandie Jefferson, Cassaundra Moore