There is no shortcut from popular art to cultural respectability. Film and television, novels and musicals, jazz, blues and rock & roll — all spent years in the wilderness of critical, if not commercial, neglect.

Few have wandered longer than comic books, direct origins of which date back to the early 1800s. Yet in recent decades — thanks to such acclaimed graphic novels as Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus (1986-1991), Daniel Clowes’ Ghost World (1997) and Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid on Earth (2000) — the form has begun to receive its critical and scholarly due.

In October, the School of Art at Washington University in St. Louis will present The Rubber Frame: Culture and Comics, a book and a pair of complementary exhibitions that together trace the evolution of comics from early precursors in England and Switzerland to turn-of-the-last-century newspapers, the raucous undergrounds of the 1960s and ’70s and contemporary alternative comics.

“Comics have long since overcome abiding prejudices about their cultural value, or lack of same,” said D.B. Dowd, a nationally known illustrator and professor of visual communications in the School of Art, who organized The Rubber Frame with M. Todd Hignite (MA 2002), editor of the award-winning Comic Art magazine.

“The innovation of The Rubber Frame will be to subject primarily American comics to multiple perspectives,” Dowd continued. “These include broader thinking about antecedents; sustained formal and content analysis; arguments about the relationship between creative strategy, technology and distribution; and reflections about representations of, and contributions from, African-American characters and artists.”

The Visual Language of Comics from the 18th Century to the Present

Washington University’s Olin Library

Oct. 1 to Nov. 30

The Visual Language of Comics from the 18th Century to the Present examines a variety of formal, technological and commercial forerunners to modern comics. Topics include early lithography and caricature; turn-of-the-last-century newspaper strips; and the birth of the prototypical staple-bound booklet.

|

WHO: Washington University School of Art WHAT: The Rubber Frame: The Visual Language of Comics from the 18th Century to the Present WHEN: Oct. 1 to Nov. 30; Reception 6 to 8 p.m. Friday, Oct. 1 WHERE: Washington University’s Olin Library, Grand Staircase Lobby and Special Collections HOURS: Olin Library: 7:30 a.m. to 2 a.m. Mondays thru Thursdays; 7:30 a.m. to 8 p.m. Fridays; 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. Saturdays; and 10 a.m. to 2 a.m. Sundays. Special Collections: 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday. INFORMATION: (314) 935-5495 |

“Legend has attributed the beginning of comics to the New York newspapering battle between Hearst and Pulitzer in the 1890s,” explained Dowd, who curated the exhibition from private collections (including the Brown Shoe Company archives); university archives; and the Center for the Humanities in Arts & Sciences’ collection of approximately 3,500 comics and graphic novels. “But recent scholarship has shown that the earliest comic strips — sequential pictures inside boxes, accompanied by captions or speeches and arranged in sequential rows — appear as early as the 1840s, while the speech bubble, a staple of the comics language, can be found in British caricatures from the 1780s and copper engravings from as early as 1730.

“The modern comic book, as we think of it today, was essentially created by the advertising industry,” Dowd added. “Printers realized they could sell more printing business by repackaging Sunday strips as advertising premiums for companies like Gulf Oil and Proctor & Gamble. The next step, taken in the 1930s, was simply to begin producing original content.”

Highlights of the exhibition include illustrations by Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827); a color proof from R.F. Outcault’s Yellow Kid, the first major comic strip character; original art from Winsor McCay’s groundbreaking Little Nemo in Slumberland; and George Herriman’s final Krazy Kat drawing (recently reprinted in the literary journal McSweeney’s all-comics issue).

The Visual Language of Comics opens with a reception from 6 to 8 p.m. Friday, Oct. 1, and remains on view through Nov. 30. The exhibition is located in the Grand Staircase Lobby of Washington University’s Olin Library, with additional material in the nearby Special Collections Reading Room.

Olin Library is located just east of Mallinckrodt Student Center, 6445 Forsyth Blvd. Lobby hours are 7:30 a.m. to 2 a.m. Mondays thru Thursdays; 7:30 a.m. to 8 p.m. Fridays; 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. Saturdays; and 10 a.m. to 2 a.m. Sundays. Special Collections hours are 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday.

For more information, call (314) 935-5495.

American Underground and Alternative Comics, 1964-2004

Des Lee Gallery, 1627 Washington Ave.

Oct. 1 to Oct. 30

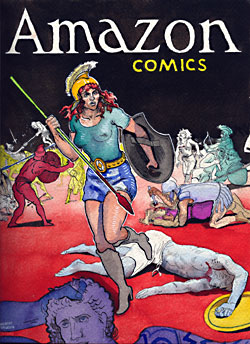

American Underground and Alternative Comics, 1964-2004 — curated by Hignite — will focus on the explosive, taboo-shattering underground comix of the 1960s and 70s and their spiritual successor, the modern alternative movement.

|

WHO: Washington University School of Art WHAT: The Rubber Frame: American Underground and Alternative Comics, 1964-2004 WHEN: Oct. 1 to Oct. 30; Reception 7 to 9 p.m. Friday, Oct. 1 WHERE: Des Lee Gallery, 1627 Washington Ave. HOURS: 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays through Thursdays; 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Fridays; 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays; 1 to 4 p.m. Sundays; and by appointment. INFORMATION: (314) 621-8537 |

The exhibition will include approximately 150 original drawings by 30 artists, including underground pioneers Robert Crumb, Kim Deitch, Spain Rodriguez, Gilbert Shelton and Frank Stack (a.k.a. Foolbert Sturgeon), the latter a longtime art professor at the University of Missouri in Columbia, whose Adventures of Jesus (1964) is widely considered the first underground.

Contemporary practitioners include Clowes, Spiegelman, Ware, Charles Burns, Gary Panter and Jaime Hernandez, the latter co-founder (with brothers Gilbert and Mario) of the seminal alternative book Love and Rockets. Also featured are three St. Louis artists, Kevin Huizenga, Ted May and Dan Zettwoch.

Highlights include several stories by Crumb, notably the four-page Jumping Jack Flash, originally published in Thrilling Murder Comics (1971); and a group of 27 preliminary drawings for Spiegelman’s Prisoner of the Hell Planet (1973), an early precursor to Maus. Other highlights include Hernandez pages and covers from Love and Rockets; examples of Stack’s work for Harvey Pekar’s acclaimed American Splendor; and a site-specific mural by Zettwoch.

“This is really a world-class show, in terms of the quality and depth of material on view,” Hignite said. “Virtually everything is culled from private collections — including those of the artists — and much of it has never been displayed before.”

“One of our goals was to contextualize things as much as possible, especially the history and larger culture surrounding the medium; the artistic process; and the means of distribution,” Hignite added. To that end, the exhibition will include examples of finished, printed comics (many from the Center for the Humanities’ collection) as well as a reading room — stocked by Star Clipper Comics, 6392 Delmar — and multimedia exhibits showcasing the form’s newest frontier, web-comics.

American Underground and Alternative Comics opens with a reception from 7 to 9 p.m. Friday, Oct. 1, at Washington University’s Des Lee Gallery, 1627 Washington Ave. Shuttle service will be available from the Hilltop Campus to the Des Lee Gallery during the opening receptions. The exhibition remains on view through Oct. 30. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesday through Thursday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Fridays, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays, 1 to 4 p.m. Sundays and by appointment.

For more information, call (314) 621-8537.

The Rubber Frame: Essays in Culture and Comics

$25, D.B. Dowd and M. Todd Hignite, editors

Published by Washington University in St. Louis

Edited by Dowd and Hignite, The Rubber Frame: Essays in Culture and Comics investigates a series of key themes and moments in the history of comics.

In her introduction, Angela Miller, Ph.D. associate professor of Art History & Archaeology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University, observes that “Comics were postmodern before the word was invented. … One of the beauties of the comic medium is its ability to use the conventions of the medium in ways that are easily understood on one level while at the same time subverting these conventions through parody. They are at once the most conventional and the most unfettered in their playful exploration of the form.”

In Strands of a Single Cord: Comics & Animation, Dowd examines the intertwining histories of those two media, from Little Nemo — which debuted as a Sunday newspaper strip in 1905 and as an animated film in 1911 — to popular crossovers such as Buster Brown, Felix the Cat and Mickey Mouse. Dowd also chronicles the recent explosion of multimedia web-based projects, including Derek Kirk Kim’s lowbright.com, Salon.com’s Dark Hotel and his own SamtheDog.com.

Daniel Raeburn, publisher of the comics ‘zine The Imp, surveys Two Centuries of Underground Comic Books, beginning with the work of Rodolphe Töpffer (1799-1846), the Swiss prep-school teacher whose humorous — and widely copied — narratives are generally considered the first true comics. Other topics include the ribald Tijuana Bibles of the 1930s; Jack T. Chick’s countercultural pamphlets of the early 1960s; and Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan, which began as a self-published booklet in Chicago.

Hignite profiles Jaime Hernandez’s “Locas”‘ the artist’s ongoing series, which dates back to 1981 and today numbers well over 900 pages. In its formal daring, conceptual sophistication and emotional complexity, Hignite argues, Locas serves as a kind of bridge between classic mid-century American comics, the underground generation and a myriad of contemporary approaches.

Finally, Gerald Early, Ph.D. — the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters in the Department of English in Arts & Sciences and director of the Center for the Humanities — considers The 1960s, African Americans and the American Comic Book. The piece investigates depictions of African Americans in mainstream comics (Fantastic Four, Mad magazine, Frontline Combat); in sports and television tie-ins (Jackie Robinson, I-Spy, The Young Lawyers); and, perhaps most complexly, throughout Crumb’s provocative oeuvre.

The Rubber Frame is published by Washington University in St. Louis and designed by Heather Corcoran, assistant professor of visual communications in the School of Art and principal of Plum Studios. The book, which retails for $25, will be available at the Des Lee Gallery and the Campus Bookstore, located in the Mallinckrodt Student Center.

Additional Events

Also opening Oct. 1 are a pair of Washington University-related exhibitions at the Philip Slein Gallery: Outlaw Printmakers — curated by printmaker Tom Huck, lecturer in Art — and Michael Byron: A Decade of Work on Paper, featuring prints and drawings by Michael Byron, professor of Art.

The Philip Slein Gallery is located at 1520 Washington Ave. Both shows open with a reception from 6 to 9 p.m. Friday, Oct. 1, and remain on view through Nov. 6. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays through Thursdays; and 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays. For more information, call (314) 621-4634, or visit www.philipsleingallery.com.

Sponors

The Rubber Frame is sponsored by the Washington University School of Art with support from Olin Library Special Collections, the Des Lee Gallery and the Visual Communications Program. Additional support is provided by the Center for the Humanities, the American Culture Studies Program and the Department of Art History & Archaeology — all in Arts & Sciences — as well as the Missouri Arts Council, a state agency, and the Regional Arts Commission, St. Louis.

Additional Images