Lead sulfide — also known by its mineral name, galena — is a naturally occurring mineral found in Missouri, other parts of the world, and now … other parts of the solar system.

That’s because recent thermodynamic calculations by University researchers provide plausible evidence that “heavy metal snow,” which blankets the surface of upper altitude Venusian rocks, is composed of both lead and bismuth sulfides.

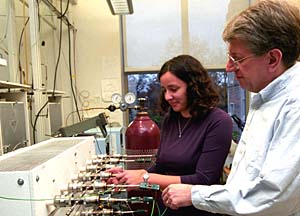

The findings — by Laura Schaefer, research assistant in the Planetary Chemistry Laboratory, and M. Bruce Fegley Jr., Ph.D., professor of earth and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences — discount previous hypotheses that the snow was made of elemental tellurium. They are important also because lead sulfide “snow” could allow the dating of Venus by lead isotopes, provided a soil sample can be obtained in a future mission.

Schaefer and Fegley’s work was published in a recent issue of Icarus, the official journal of the Division of Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society.

“We calculated the equilibrium compositions for 20 trace metals in Venus’ lower atmosphere, looking for something that condenses at this altitude of 2.6 kilometers,” Schaefer said. Previous analyses, she added, simply “didn’t consider any chemistry. When we looked at the chemistry, we found that the best candidates were actually lead and bismuth sulfides.”

Discovery of the metallic snow dates back to 1995, when Raymond E. Arvidson, Ph.D., the McDonnell Distinguished University Professor and chair of earth and planetary sciences, and other researchers were analyzing the vast archives of data taken from NASA’s Magellan mission to Venus in 1989.

Magellan’s primary objective was to map the surface of Venus using a technique known as synthetic aperture radar (SAR). SAR images taken of Aphrodite Terra and other mountainous regions in Venus’ highlands revealed a mysterious brightening effect.

Using computers to factor in physical parameters such as elemental abundances — what elements are present and in what amounts, altitudes, temperatures and pressures — researchers surmised that the brightening effect was due to a metal-containing “snow” only a few millimeters in thickness frosting the mountains’ rugged surfaces.

But even as the hypothesis of metallic snow was circulating throughout the planetary community, its chemical composition remained largely an educated guess — one among many on the short-list of 98 possible metal-containing compounds that commonly exist around volcanic vents on Earth.

“An old idea we had was that you have compounds of these trace metals being erupted and condensing around volcanoes on Earth,” Fegley said. “Now on Venus, which is much hotter than Earth, you’d have a similar process: You’d be erupting these trace metals, which would then stay in the gas phase until they reached a high enough atmospheric level where they’d condense.

“Because you have a decrease in temperature with altitude, places like the Maxwell Montes on Venus — similar to Mauna Loa in Hawaii — get cold enough that some of these things would start to condense out.”

The researchers took the list of possibilities and used their expertise in chemical thermodynamics to help them narrow the pool of suspects. In this case, whether a particular compound remained a plausible candidate was governed by two factors: thermodynamics — the rules that predict chemical stability based on environment — and the chemical profile of Venus, which was obtained from earlier American and Russian data-gathering missions.

“One of my old professors from MIT (Gordon Pettengill, the principal investigator for the Magellan SAR project) did an experiment that proved our model for the (existence of) metallic snow, but he suggested tellurium,” Fegley said. “I decided to re-examine the issue in early 2003.”

Schaefer and Fegley carefully considered what could happen to tellurium after it was introduced into the Venusian atmosphere by a volcanic event. But they went a step further by allowing it to undergo reactions with other volatile species present in the atmosphere.

As it turns out, sulfur dioxide is the third-most-abundant gas on Venus and is a major contributor to the thick layer of sulfuric acid clouds that envelope the planet. According to thermodynamic equations, any significant concentration of volatile tellurium would react with these sulfur-containing compounds to make tellurium sulfide, a relatively stable gas.

“So it can’t just condense out because it’s undergoing chemical reactions instead,” Fegley said.

Lead sulfide and bismuth sulfide were identified as front-runners thanks to a specific physical property called a dielectric constant — an intrinsic value describing a material’s electrical conductivity — that Magellan’s SAR measured in 1991.

“Typical volcanic rocks have a dielectric constant of a few, maybe 4, but the stuff that Magellan saw in the highlands of Venus was much higher, about 100,” Fegley said. “In order to have a dielectric constant that high, you have to have something that’s either a semiconductor or a conductor, and actually, these minerals that we’ve proposed condensing, the galena (lead sulfide) and the bismuth sulfide, have dielectric constants that are basically — BANG! — right on.”

If Schaefer and Fegley are right, having “snow” made of lead sulfide could have implications beyond confirming their own work; it could be used as a means of dating the beginning of Venus’ existence.

So how exactly would that work? By the same process that scientists have used to date the age of the Earth — lead dating — using the ratios of different lead isotopes (which differ only in number of neutrons).

All of these lofty dreams rest on there being an actual sample of dirt to analyze; a dream that could become reality with one of NASA’s New Frontiers Missions, a competitive $650 million endeavor to be selected for funding in the next year or two.

Venus aficionados like Fegley are pushing for a more comprehensive probe of the Earth’s nearest neighbor. Their mission would include a detachable landing module that could perform geochemical analyses in the highlands using techniques like X-ray fluorescence and X-ray diffraction.

“All these ideas — these calculations — can be tested by one of these New Frontiers spacecrafts, if the Venus mission is picked,” Fegley said. “What makes this type of work exciting is the fact that these ideas could be tested by spacecrafts that are on the drawing boards today.”