In 1922, art historian Josef Stryzgowski warned an audience at Boston’s Lowell Institute of the impending “crisis in the humanities.” Nearly a century later, Stryzgowski’s theme remains a staple of op-ed pages and Thanksgiving interrogations alike. What, generations of English majors have been asked, are you going to do with that?

But even hypochondriacs catch cold. In the wake of the Great Recession, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, undergraduate degrees conferred in English language or literature fell roughly a quarter, from 55,465 in 2009 to 41,317 in 2017. At Washington University in St. Louis, the number of English majors dipped from 155 in 2013 to just 99 in 2018.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the funeral, said Abram Van Engen, professor of English in Arts & Sciences. “Over the last three years, WashU’s undergraduate English major has grown by about 30 percent,” he explained. Current enrollment stands at 131.

“We’re bucking the trend.”

A powerful mythology

Critics of the humanities often frame their arguments in terms of economic rationalism. “Folks can make a lot more, potentially, with skilled manufacturing or the trades than they might with an art history degree,” quipped President Barack Obama. “Welders make more money than philosophers,” added Sen. Mark Rubio. Cuts to humanities programs are justified in the language of jobs and employment.

“It’s a powerful mythology,” said Vince Sherry, the Howard Nemerov Professor in the Humanities and chair of the Department of English. “No one wants to climb onto a dying branch. But in a world that’s changing ever more quickly, a degree can’t just be a ticket to one particular job. Students need to acquire the capacities, aptitudes and ways of thinking that will allow them to grow into their changing futures.”

It’s true that, for those with bachelor’s degrees, median lifetime earnings in the humanities are modestly lower ($2.4 million) than in health or the physical sciences ($2.9 million), according to a new report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce.

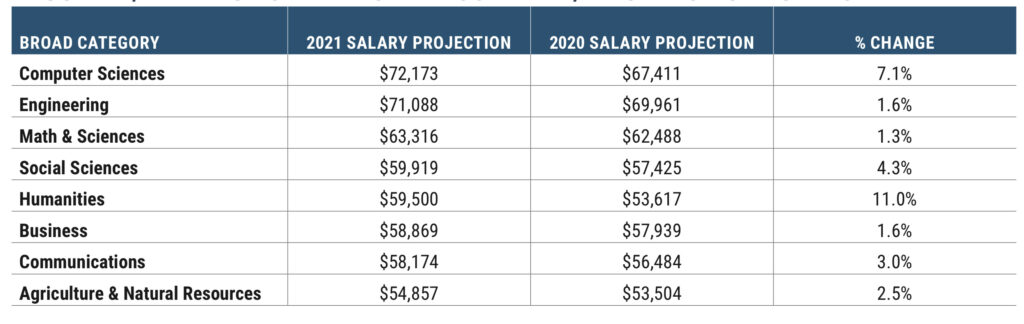

But the gap may be narrowing. A working paper at the National Bureau of Economic Research posits that the rapid pace of technological transformation, which rewards STEM graduates with the latest training, also leads to “flatter age-earnings profiles as the skills of older cohorts became obsolete.” Meanwhile, the National Association of Colleges and Employers projected that for 2021, average starting salaries in math and science would rise 1.3%, to $63,316, while those in the humanities would rise 11%, to $59,500.

The upshot, Van Engen argues, is this: “The major problem for humanities majors in general and English majors in particular is not one of career outcomes. It is a problem of perception.”

Building a counternarrative

To combat such perceptions, Washington University’s English department is reexamining the ways it recruits, supports and communicates with undergraduate students. Leading efforts have been Sherry and William Maxwell, professor of English and of African and African American studies, who directed undergraduate studies in English from 2018-2021. Van Engen, as Dean’s Fellow for Educational Initiatives and Innovations, worked closely with both.

“The first hurdle is just reaching people early,” Van Engen said. To that end, the department increased first-year course offerings while encouraging faculty to explore broad, multidisciplinary themes. For example, Van Engen’s “Morality and Markets” class — co-taught by Peter Boumgarden at Olin Business School as part of the first-year Beyond Boundaries series — uses the tools of literary scholarship to explore business ethics.

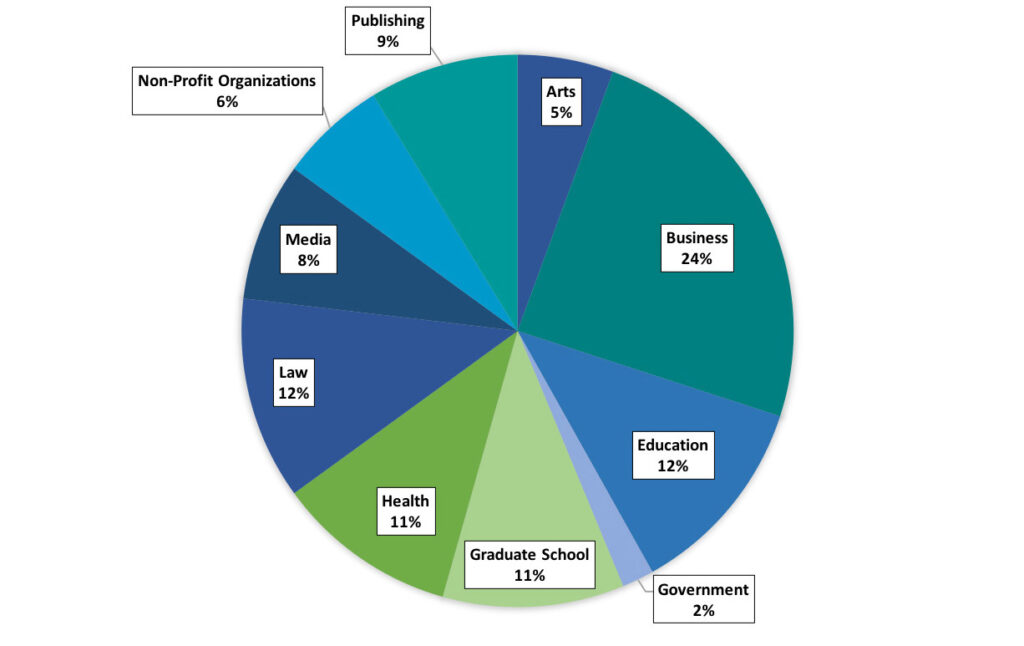

The department also developed an alumni database to help track career trajectories. For example, it found that 23% of WashU English majors went on to law or medical school, with 24% working in business-related fields. Another 23% work in education or have pursued advanced degrees in the humanities. Other common paths include publishing (9%), media (8%), nonprofit organizations (6%), the arts (5%) and government (2%).

“In the humanities, we don’t talk enough about jobs,” Van Engen said. Historically, some humanities fields have been wary of presenting themselves in vocational terms, yet this reticence creates an information vacuum for potential majors.

“Eventually, students will leave college and have to get a job,” Van Engen added. “And I think it’s important that we celebrate what our graduates are actually doing in the world.”

The social dimension

The final piece of English’s recruitment puzzle was less a matter of policy or research than of culture and communication.

“Reading and writing and talking about literature are at the core of the program,” Sherry said. “But we also really emphasize the social dimension. It’s important that students get to know one another and have experiences together — everything from seminars and critiques to bowling night and scary poetry on Halloween.

“This is a really strong department,” Sherry added. “We want students to experience that vitality and exuberance.”

Each fall, Sherry invites first-year students who’ve indicated an interest in literature or creative writing to a departmental open house. “When we started, we had about eight students attend,” he recalled. “This year, we had more than 50.” He also asks faculty to recommend promising students and often follows up personally to see if those students have considered an English major. “If you do the outreach, they will come.”

Sherry also points to the strength of the Creative Writing Program, regularly ranked among the nation’s best. “Within the English major, we’ve made it possible for undergraduates to concentrate in creative writing and that has really sustained us through the hardest times,” he said. “Our students are smart, motivated and intellectually curious. They want to give that curiosity shape and direction. And we can help them, one by one.”

Feng Sheng Hu, dean of the faculty of Arts & Sciences and the Lucille P. Markey Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences, noted that this multifaceted approach to recruiting and supporting exemplifies the department’s entrepreneurial ethos.

“Thoughtful, intentional efforts like these pay off in terms of the educational experience we provide, and our students feel those benefits firsthand,” Hu said. “I’m incredibly impressed with the gains English has seen, and I believe we’re feeling this momentum across the humanities in general.”

Interdisciplinary study

The department’s efforts coincide with a larger, universitywide emphasis on supporting interdisciplinary study. Today, more than a third of WashU undergraduates pursue two majors, sometimes across different WashU schools. Another third pursue at least one minor.

“I’ve always loved the humanities, especially English, but I also had a curiosity about applied art and design,” said Isabelle Celentano, who graduated last May with a bachelor’s in English as well as minors in art history and, from the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, communications design. “I think that’s what drew me to WashU.”

Less than a week after graduating, Celentano accepted a position at Applied, the New York-based branding and design firm. “Everything I did at WashU is now really helping me in the career I’m pursuing,” she said. “All the reading and writing — and presenting! — I did for my English classes trained me to process and synthesize information quickly. And the ideas and vocabulary I learned in my design classes help me to communicate with both our clients and our internal teams.”

“What we’re seeing in English and other literature departments is an opening up of the disciplines to insights from a variety of academic inquiries across Arts & Sciences,” said Erin McGlothlin, vice dean of undergraduate affairs in Arts & Sciences. “This allows students to combine their interests in unique ways and helps them to prepare for their post-graduate lives, whether in graduate study or in the workplace.”

McGlothlin gives the example of cognitive narratology, which draws on neuroscience to explain how the human mind processes stories. “Students of English who delve into this area not only come away with a greater appreciation of the importance of narratives in human cognition,” McGlothlin said, “but are also able to apply what they have learned in a variety of settings.”

Amanda Arbuckle earned bachelor’s degrees in English and cognitive neurosciences last May, as well as a minor in religious studies. She’s currently a research assistant in the School of Medicine and, after a gap year, plans to apply to doctoral programs in psychology.

Arbuckle says that, from an early age, her grandfather, a psychiatrist, and mother, a psychiatric social worker, emphasized the importance of understanding how the brain works while also imparting a love for literature. On college tours, she’d regularly ask about the potential for studying both fields, and chose WashU for that reason.

“I enjoyed going from discussing Spenser or Jane Austen in my humanities courses to learning about aging and cognitive control in my neuroscience courses,” Arbuckle recalled. “I wish more of my friends had that experience.” She also points out that, for all the supposed divides between the humanities and STEM, neither has a monopoly on creativity or rigor.

“We all want to see the full picture of what’s inside the mind.”