If you walk along the High Line in New York City, an elevated park in West Chelsea and one of the most coveted real estate districts in Manhattan, you’ll see buildings by Robert A.M. Stern, Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel and Zaha Hadid. Many consider it a display of the top architects of our era. Also along it are two buildings by architect and developer Soo K. Chan, AB ’84: the Soori High Line, a 31-unit condo, and 515 Highline, a 12-unit condo.

While 515 Highline has the flashier exterior with its curvy glass waves and large, rotating art exhibition wall, it was the Soori High Line that caused the most excitement when plans were announced in 2014. The building features 18-foot ceilings, walls made of a single sheet of glass, and 16 of the condos have private saltwater pools.

SCDA Soori High Line, photo by Aaron Pocock

The Khoo Kongsi compound, photo by Supanut Arunoprayote

SCDA Soori Bali, photo by Mario Wibowo

Born in Malaysia, Chan grew up in the Khoo Kongsi compound in Penang. The Khoo clan settled on the island in the mid-1800s and built the temple, which was surrounded by row houses. Chan’s mother was Khoo, and he lived in the compound until he was 4.

“We would slide up and down the stone banister on the temple and just run wild,” Chan told the Wall Street Journal. “Everyone was related somehow and looked after us, so we were safe.”

Now, the area is a much-visited UNESCO World Heritage site, and no one lives there. Despite leaving when he was young, Chan remembers his house well. “My house was long, maybe 16 feet wide and 50 to 60 feet long, and you would have two or three open-to-the-sky courtyards that brought in light and air to the rooms behind. When it rained, the elements came in, and you didn’t stop it. You let it pour into the sunken courtyard, and it momentarily fills up before it gradually drained out. It was probably my first encounter with phenomenology. And that connection to the senses and the climate and to nature, it’s powerful. It still influences my work today.”

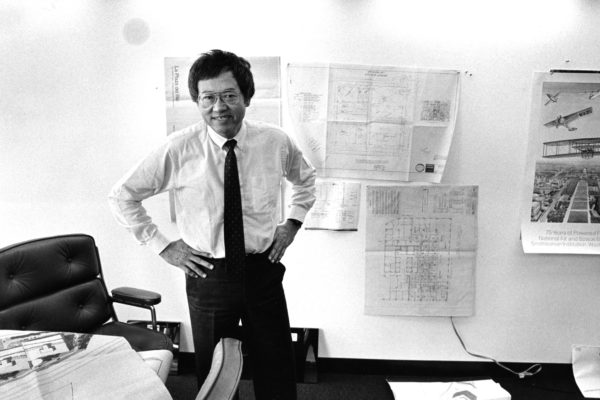

By the time he was 12 or 13, Chan had decided to become an architect. He liked to draw, and used to visit sites with his father who was doing some development in his native Penang. He discussed with a teacher that he wanted to go to America to study architecture.

“‘OK, go look at these books,’” Chan remembers the teacher telling him and directing him to a small vocational guidance room. Among the brochures, he found one for WashU. “I didn’t know exactly where it was,” Chan says. “At that time, I wanted a diverse student body and even in 1980, WashU had quite a good mix of students. I looked at pictures of the campus, the lawn looked nice, and the architecture program was highly ranked. So I said ‘OK’ and applied there.”

Learning Bauhaus

Chan moved into Liggett in August of 1980, and found himself sitting in studios with the late Leslie Laskey, then a professor of architecture. “I talk about him quite a bit, even now,” Chan says. “He taught the foundation design classes for your freshman year. And, obviously, the professors that have a high impact your first year stay with you. He was one of those teachers.”

“Bauhaus is a whole movement about how design is all encompassing. It even includes dance, for example, as part of architecture.”

Soo K. Chan

Chan did his graduate work at the Yale School of Architecture. “It was a very interesting time to study architecture,” Chan recalls. “It was a very permissive time in terms of design theories. There were a lot of different thought movements like postmodernity, deconstructivism, poststructuralism, historian, and I was confused. Through the studio lottery system I ended up with a classical studio.”

After graduating, Chan worked for architect Allan Greenberg, a classicist in Virgina who worked on projects in the state department in an orthodox classical style.

“I just thought I wanted to go back to something very conservative and understand the basics. It was good after a few years of exploring to narrow it down a little bit,” Chan says. He then moved to New York City, working for Kohn Pederson Fox before returning to Singapore in 1990 and starting his own practice in 1995.

When he returned to Singapore, he started designing houses in a holistic manner encompassing architecture, interiors and landscape. Chan is known for his attention to detail. At his own resort at Soori Bali which he designed, developed and operates, Chan designed everything from the plates to the furniture to the graphic design elements. He traces this passion back to his undergraduate years learning formative design processes.

“At WashU, they didn’t just teach you architecture immediately,” he says. “I remember the first two studios I took were basically just about making things, understanding materials, a way of thinking about design.”

The basic design studios on architecture supported this holistic approach. “Bauhaus is a whole movement about how design is all encompassing,” Chan says. “It even includes dance, for example, as part of architecture. I think Leslie Laskey was very much teaching in the Bauhaus tradition.”

A 360-degree view

In 1995, Chan founded Soo Chan Design Associates (SCDA), a company with a holistic approach encompassing architecture, interiors, landscape and product design.

“I first started incorporating gardens into single-family houses, inserting them in between rooms by breaking closed volumes into a system of pavilions. As the scale of my projects grew, I incorporated these green spaces into larger and taller projects,” he told ArchDaily.

SCDA has designed more than 200 buildings in over 75 international locations worldwide. The firm’s accolades include three awards from the American Institute of Architects, and two from the Royal Institute of British Architects. Chan is also the inaugural recipient of the Singapore President’s Design Award.

For one project, Sky Terrace@Dawson, Chan was tasked with reimagining public housing in Singapore. The government wanted to develop a new paradigm for a Singapore social housing project. The three main ideas Chan introduced are housing in a park, multi-generational living and sustainable living.

The project’s landscape is an extension of the adjacent linear park that was introduced over an abandoned canal. There is also extensive landscaping and roof terraces in the sky. The greenery is natural and is extended vertically up the entire building while being irrigated by water collected from the roof and surface run offs through bio-swales around the gardens. The common area relies extensively on cross ventilation and natural light to reduce power consumption.

The idea of multi-generational living was something Chan understood well. The lifestyle of the extended Singaporean family often relied on grandparents for child care as most couples are dual income families.

“They were driving across town to drop off and pick up their kids,” Chan says of the families. “We introduced the concept of interlocking spatial modules you can purchase as a pair, including a grandparent flat, and it stacks on top of yours with its own entry and an interconnecting staircase that has connecting doors.”

The units are all modular and pre-fabricated of precast concrete. “We’re encouraging a kind of social housing experimentation of how extended families can live together,” says Chan. This concept was in line with government policies at that time. There are some tax incentives when multi-generational families apply to purchase the flats together. “The young adult generation can look after the elderly, and they in turn can watch after the kids.”

Sky Terrace, with almost 700 units of flats, has amenities that support all ages in this community. It has a child-care center, elderly care center, a congregation area for wedding ceremonies, places for worship and also a space for wakes and funerals.

Chan is continuing to develop new Soori branded projects, the latest being Soori Wyoming. He hopes to turn part of the Khoo Kongsi compound, where he grew up, into a Soori hotel. His design, according to one writer, “is a sensory mechanism, an invitation to linger, to dwell in these interior and exterior spaces.”