An immunotherapy based on supercharging the immune system’s natural killer cells has been effective in treating patients with recurrent leukemia and other difficult to treat blood cancers. Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown in preclinical studies conducted in mice and human cells that this type of cell-based immunotherapy also could be effective against solid tumors, starting with melanoma, a type of skin cancer that can be deadly if not caught early.

The study is published June 29 in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

In recent years, an immunotherapy called immune checkpoint inhibitors has revolutionized treatment for advanced melanoma. In one well-known example, this immunotherapy was successfully used to treat former President Jimmy Carter, whose melanoma had spread to his liver and brain.

But the therapy only works in about half of such patients. And even among those who respond well to the initial therapy, about half go on to develop resistance to it. Consequently, researchers have been seeking different ways to harness the immune system to attack melanoma cells. One possibility is to use natural killer (NK) cells, a part of the immune system’s first line of defense against dangerous cells, whether cancer cells or invading bacteria.

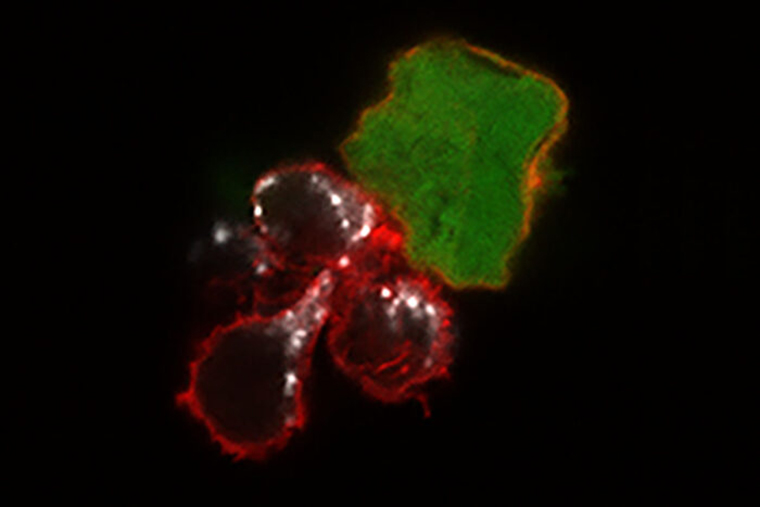

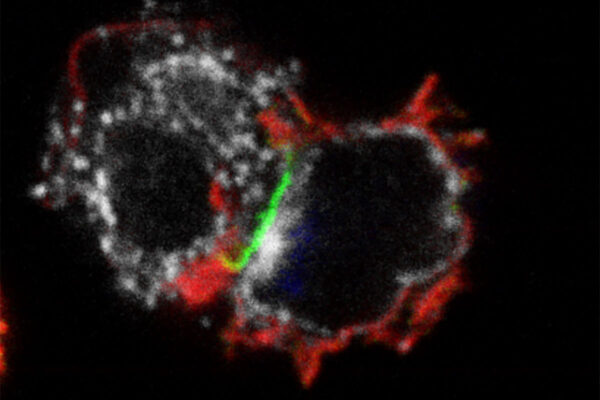

Todd A. Fehniger, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, and his team have had success in clinical trials treating recurrent leukemia with a patient’s own natural killer cells or those from a donor. The NK cells are harvested from the patient’s or a donor’s blood and exposed to a set of chemical signals called cytokines that activate the cells and prime them to remember this activation. When these “cytokine-induced memory-like” NK cells are given to the patient, they are more potent in attacking the cancer because they already have been revved up, as Fehniger puts it.

“These ‘revved-up’ memory-like NK cells attack blood cancers quite well,” said Fehniger, the study’s co-senior author and an oncologist who treats patients at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine. “But relatively little work has been done on whether these cells can be used against solid tumors. This is an unmet need in solid tumor oncology. Our study provides proof of principle that memory-like NK cells respond better than normal NK cells against melanoma, and it serves as a stepping stone to a first-in-human clinical trial of these cells in advanced melanoma.”

Added co-senior author Ryan C. Fields, MD, the Kim and Tim Eberlein Distinguished Professor of Surgical Oncology: “We hope this is also a step toward harnessing NK cells against multiple solid tumors. Melanoma was a good place to start because we know it responds to immune therapy. But because many patients don’t respond or develop resistance, we felt that targeting a different aspect of the immune system was a promising strategy to pursue.”

The standard checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy that works well in some melanoma patients targets T cells, another type of immune cell that also frequently is harnessed against different forms of cancer. According to the researchers, patients who don’t respond well or stop responding to the T cell-based standard therapy and have no other options would be good candidates for NK cell therapy.

The researchers studied human NK cells from both healthy people and from patients with melanoma and found that the cytokine-induced memory-like NK cells could effectively treat mice harboring human melanoma tumors. Tumors shrank to the point of being almost undetectable in many of the mice, and the memory-like NK cells prevented the tumors from returning in most cases for the duration of the 21-day experiment. While normal NK cells also reduced and controlled melanoma tumors, they did not do so to the same degree.

“We are currently designing a clinical trial to evaluate these NK cells in patients with advanced melanoma who have exhausted all other treatment options,” Fehniger said. “We would like to investigate NK cells from a donor and, separately, a patient’s own NK cells to see if the cytokine-induced memory-like NK cells offer an effective treatment option for patients with this aggressive skin cancer.”

The NK cell-based immunotherapy is potentially safer than other cell-based immunotherapies because the NK cells do not trigger a cytokine storm, as is seen sometimes in CAR-T cell therapy, which often is used for blood cancers, nor do the NK cells cause graft-versus-host disease, which sometimes follows a stem cell transplant.

“Even 10 years ago, we had no effective therapies for advanced melanoma — much like the lack of therapies for glioblastoma or advanced pancreatic cancer today,” said Fields, a surgeon who treats patients at Siteman. “Checkpoint immunotherapy has revolutionized melanoma treatment, but we’re still not satisfied with the 50% response rate. We want to do better, and this NK cell therapy is a promising approach. And in the future, we may be able to combine an NK cell-based therapy with checkpoint inhibition for an even better response.”

Fehniger and his colleagues have worked with Washington University’s Office of Technology Management to license the cytokine-induced memory-like NK cell technology to a company called Wugen. Fehniger is a co-founder of Wugen and serves on its scientific advisory board.

Fehniger and co-author Melissa M. Berrien-Elliott, PhD, an instructor in medicine, are consultants and have equity interest in Wugen and may receive royalty income based on technology they developed and that was licensed by Washington University to Wugen.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant numbers T32 HL007088; R01CA248277, R01CA205239, CCSG P30 CA091842, NIHU54CA224083, K12CA167540, and a SPORE in Leukemia P50CA171063. Additional funding was provided by a Sidney Kimmel Translational Science Scholar Award; a Society of Surgical Oncology Clinical Investigator Award; the David Riebel Cancer Research Fund; the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society; the V Foundation for Cancer Research; and the AAI Intersect Fellowship Program for Computational Scientists and Immunologists. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Washington University School of Medicine Surgical Oncology Basic Science and Translational Research Training Program, grant number T32CA009621 from the National Cancer Institute. Further support was provided by the Siteman Flow Cytometry Core; the Immune Monitoring Lab; the Siteman Tissue Procurement Core; and the core grant/services of the Washington University Digestive Diseases Research Core Center, grant number P30 DK052574.

Marin ND, et al. Memory-like differentiation enhances NK cell responses to melanoma. Clinical Cancer Research. June 29, 2021.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 1,500 faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is a leader in medical research, teaching and patient care, consistently ranking among the top medical schools in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.