Welcome back to Class Acts, a celebration of the Class of 2021. This week, we celebrate three graduating students who are leaders in research — Churchill Scholar Jessika Baral, Spencer T. Olin Fellow Chelsey Carter and U.S. Army veteran Alex Reiter.

It started back in middle school, when Jessika Baral got glasses and her dad was struggling with his cataracts.

“He suggested that we do eye exercises together,” Baral recalled. “Middle-school Jessika was not down for that.”

So she engineered a sort of sombrero festooned with LED lights. By following the blinking lights, users could strengthen their eye muscles. The results were so impressive, Baral was invited to the White House Science Fair, where she met her hero, Bill Nye.

Fast forward to today. Baral is set to earn her undergraduate degree in biology from Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. She has conducted cancer research at Stanford and Washington universities; co-authored papers in leading journals; founded dance education nonprofit Our Chance to Dance; and won the Barry Goldwater Scholarship and the Churchill Scholarship, which provides a free graduate education at the University of Cambridge, where Baral will study computational biology.

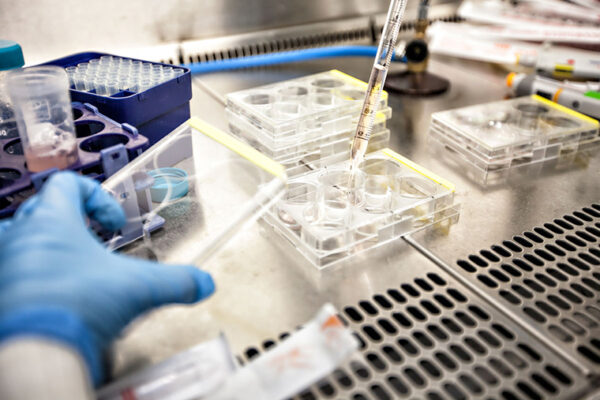

“Computer science is going to be a huge part of the future of medicine,” said Baral, who most recently used computational biology in the Ding lab at the School of Medicine to determine which protein complex formations can lead to cancer. “By integrating the computational and the experimental, we can ask new questions and really accelerate discovery.”

Baral ultimately wants to go to medical school to train to be a pediatric oncologist. She also wants to be a mentor to female scientists — much as Li Ding at the School of Medicine has been to her. To that end, Baral helped launch WashU Women in STEM, which provides a community, professional development and outreach programs.

“I don’t know where I would be without all of the amazing mentors in my life,” Baral said. “I just want to pay that forward.”

— Diane Toroian Keaggy

Chelsey Carter centers her research on the illness experience of Black and white Americans living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in her hometown of St. Louis. Her experience working in clinics and hospitals in St. Louis and Atlanta helped her to see how structural racism could impact care in different ways, depending on local circumstances.

“When you’re not willing to talk about racism — or to acknowledge that racism could be happening — then you start putting blame on individuals instead,” Carter said. “In St. Louis, many of the clinicians I spoke with weren’t willing to acknowledge the systems of oppression that are creating inequitable care.”

Her dissertation is titled “It’s a ‘White Disease’: ALS, Race, and Suffering in a Divided City.” The project demonstrates the ways racism, gender discrimination and class biases complicate the experiences of people living with ALS in St. Louis.

Carter recalled the ice bucket challenge.

“I started asking questions about the experiences of having ALS — this incurable disease — that had a viral moment at the same time that Ferguson was happening,” Carter said. “St. Louis has a history and a present with extreme racial tensions. How is that impacting people who are considered to have a ‘white disease’?”

“Chelsey’s groundbreaking work with Black patients with ALS illuminates the pernicious effects of white supremacy in the constitution of medical knowledge and the delivery of care,” said Rebecca Lester, professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences and Carter’s thesis adviser. “Through careful, compassionate and rigorous ethnography, she centers the experiences of those who historically have been silenced and leads readers to interrogate their own assumptions about what counts as medical ‘facts,’ what constitutes responsive care and who is seen to be deserving of quality treatment.”

In July, Carter will become a presidential postdoctoral research fellow at Princeton University, where she will continue work on her book. She has accepted a tenure-track position as an assistant professor at the Yale School of Public Health, beginning in July 2022.

— Talia Ogliore

When Alex Reiter was on active duty, one of his responsibilities was designing physical training programs. Sometimes things didn’t go well.

“People I was in charge of would get overuse injuries,” he said. He saw similar injuries throughout the Army and wanted to understand why.

He imagined getting a biomechanics master’s degree, then working in industry.

In 2015, he and his wife, Leigh, were ready for a change. Reiter transitioned to the Army Reserve. Then in Kentucky, he applied to Washington University. The move would put the Quincy, Ill., native and his wife, a Missouri native, closer to family.

Reiter reached out to David Peters, the McDonnell Douglas Professor of Engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering. He shared his background and motivation to earn a master’s degree. Peters suggested a PhD.

“I didn’t even know what a master’s student, or PhD student, or even research looked like,” Reiter said. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 2010, followed by a six-year active duty military career. Reiter talked it over with his wife.

“Leigh is a big reason I have been able to pursue my PhD,” he said. “We’ve had three boys along the way — Graham (4), Owen (2), and Jay (4 months).”

Reiter researches traumatic elbow injuries and ways that physical therapy-based approaches can restore function.

“How can we train the best way possible, meet the demands of the Army, and keep people healthy and safe?” he asked.

Now he is about to graduate with a doctorate in mechanical engineering.

Reiter begins this summer as a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Ultimately, he wants to run a lab researching the biomechanics of military-related injuries.

“I thought it would be impossible to do what I wanted because of my background,” Reiter said. “Looking back, WashU is the best place I could have ended up.”

— Brandie Jefferson