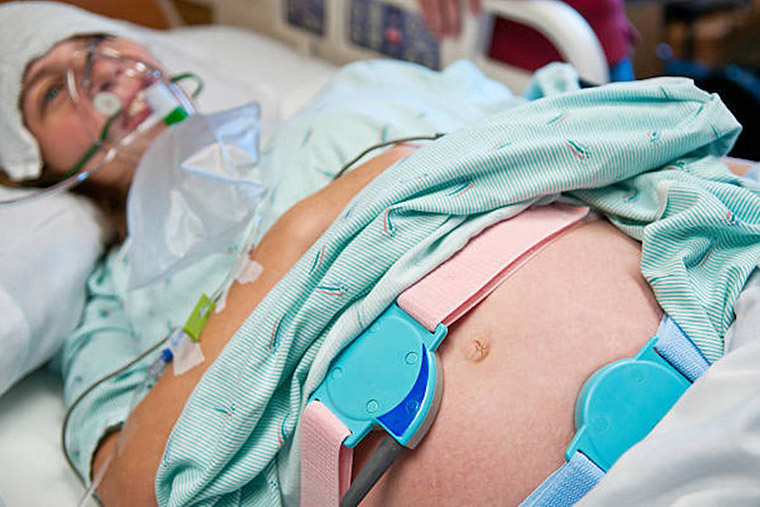

Babies who suffer oxygen deficiencies during birth are at risk of brain damage that can lead to developmental delays, cerebral palsy and even death. To prevent this, most women in labor undergo continuous monitoring of the baby’s heart rate and receive supplemental oxygen if the heart rate is abnormal, with the thought that this common practice increases oxygen delivery to the baby. However, there is conflicting evidence about whether the long-recommended practice improves infant health.

Now, a comprehensive analysis — led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis — looking at 16 previous trials of the practice has found no benefit in providing supplemental oxygen to mothers during labor and delivery. Infants born to women who received supplemental oxygen fared no better or no worse than those born to women who had similar labor experiences but breathed room air.

The findings are published Jan. 4 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Each year, 1.5 million women in the U.S. — two out of three pregnant women — receive supplemental oxygen at some point during childbirth, according to the researchers.

The decades-long practice is recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to treat abnormal fetal heart rates, which may indicate the baby’s oxygen levels are low and pose health risks.

“It is such a common practice because the thought is that by giving mom oxygen, we are increasing oxygen transfer to the baby,” said the study’s first author, Nandini Raghuraman, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. “However, the results of this study suggest that oxygen is not helpful in these cases and that the practice could be safely discontinued for many women.”

Raghuraman added that supplemental oxygen is given mostly as a preventive measure, a practice that began during the 1960s. “Fetal monitoring can indicate a possible abnormal issue such as oxygen deprivation,” she said. “But about 80% of the time, women giving birth fall into an intermediate category, in which cases are not completely benign but also not high-risk. And in cases such as these, supplementing oxygen offers no additional benefits.”

For the analysis, the researchers examined 16 studies published from 1982 through 2020 of randomized controlled trials in humans — including one from School of Medicine researchers — involving more than 2,052 women in childbirth. “Overall, the studies produced mixed results, with some indicating a benefit and others indicating no benefit,” Raghuraman said. “That was the reason for doing a meta-analysis. By pooling the numbers of patients across the studies we could get a more definitive answer than looking at individual studies.”

The researchers evaluated the pH levels of the babies’ blood from samples taken shortly after birth. The pH measures the body’s acidity and alkalinity in blood and other fluids, with neutral equaling pH value of 7. For infants, Raghuraman said anything less than 7.1 is considered abnormal and indicates oxygen deprivation.

The researchers also compared neonatal intensive care admission rates and Apgar scores — a well-established test to evaluate newborn health at one and five minutes after birth. Apgar scores check a baby’s heart rate, breathing and other signs to determine if the baby needs additional medical care.

“Comparing the health of the babies whose mothers received oxygen and those whose mothers didn’t, we found that the differences were essentially zero,” Raghuraman said.

Forgoing oxygen supplementation would help reduce an unnecessary intervention and likely reduce health-care costs. “It’s been shown that moms, despite having health insurance, often incur steep out-of-pocket costs related to childbirth,” Raghuraman said. “Although oxygen is generally an inexpensive intervention compared with other labor and delivery services, minimizing any unnecessary procedure is important.”

At Barnes-Jewish Hospital, where Raghuraman delivers babies, the findings have begun to influence clinical care. “We’re being more judicious about giving supplemental oxygen to women during labor.”

Past studies have indicated that supplementing oxygen may be beneficial to women delivering via cesarean section; however, Raghuraman said more research is needed. “We also want to look at whether exposing mom and baby to prolonged oxygen during labor may be harmful,” she said. “Outside of labor and delivery, a lot of research shows that over-oxygenation is associated with oxidative stress that can cause the kind of cellular damage that has been implicated in conditions such as cerebral palsy and Alzheimer’s disease. Our findings contradict a general myth that oxygen bars and other ways of increasing oxygen intake is healthy and helpful to a person’s overall well-being.”

Also contributing to the study were researchers from Atrium Health Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C.; the University of Texas at Austin; and Indiana University in Indianapolis.