When Bill Danforth became chancellor of Washington University in 1971, he was a doctor brought in to help heal a deeply wounded, profoundly ailing institution. Perhaps most appropriately, he was by training a cardiologist, and it was the very heart of the university that was suffering.

In the years following World War II, thanks to the GI Bill of Rights, returning veterans (nearly all first-generation college students) flooded U.S. campuses, transforming them from sustainers of privilege to engines of intellectual and democratic change. Universities enjoyed a new relevance, remade by individuals who had returned from battlefronts looking for more than a degree, equipped with broader concerns than mere ambition.

It was an exciting time, and the new energy it brought to learning, practical as well as abstract, gave the academy a respect in America it had never previously enjoyed. Those returning from the carnage of war seek answers to profound questions, and the late 1940s and 1950s were a golden age for the liberal arts. But ex-soldiers also arrive on campus older than other generations of students and are eager to get on with their lives, to pursue careers and start families. Under such conditions, the gap between professional and general education can be narrowed, the search for meaning made, necessarily, more compatible with preparation for employment.

It is significant that Bill Danforth belonged to this generation of students. Though he was younger than the returning vets, his school years overlapped with theirs. By this association, I suspect, he began to see that education itself can be an instrument of healing, can provide a means of social reformation.

The GI Bill addressed some of America’s inequities, but most remained. And by the 1960s there was an explosion of old grievances, demands for a justice too long delayed. It is obvious in media images and reports from that time that Washington University (and America) was torn apart by the war in Vietnam. Anti-war demonstrations dominated the headlines, but we were more deeply damaged, more profoundly afflicted by a persistent collaboration with systemic racism and sexism. Our student body, handicapped by decades of Jim Crow segregation, remained nearly all white, and our faculty was very nearly all male as well as all white.

What ailed the university when Danforth stepped to its helm was far more than disagreement about a reckless and destructive war. Rather, ours was a disease that threatened the very reason for our existence, that being the educational empowerment of free men and women to be free men and women. We were a house divided over much more than what was going on in Southeast Asia.

Bill, born white and male and privileged, could have sat this one out. He was, after all, a physician. Who could have challenged his service to others, his humanitarian contributions? Why take on anything more?

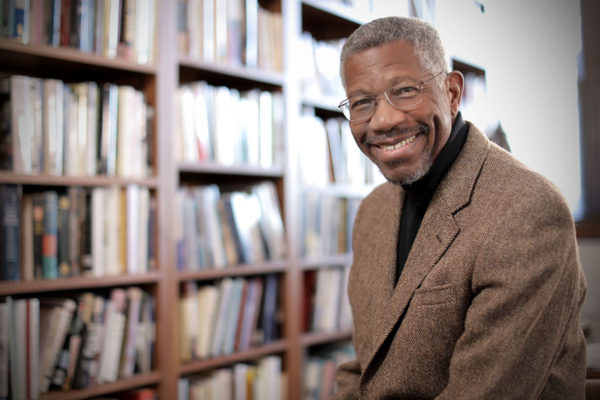

“Bill’s greatest talent was his ability to hear other people, and that listening, even more I suspect than his undergraduate years at Princeton, provided his liberal education, the constantly broadening perspective that made him a great academic leader.”

Wayne Fields

Bill grew up in a family where service was expected. His grandfather had authored a popular self-improvement book, I Dare You, that emphasized responsibility to others and on which every Danforth child surely cut his or her moral teeth. But whatever conclusions the historians reach, the primary explanation for Bill Danforth’s accomplishments at Washington University is that he cared about people, everyone he met, and respected them regardless of race or gender or economic circumstances. And he listened to them. Bill’s greatest talent was his ability to hear other people, and that listening, even more I suspect than his undergraduate years at Princeton, provided his liberal education, the constantly broadening perspective that made him a great academic leader. Bill listened to the men with whom he served and whom he treated during his time as a medical officer aboard a Navy destroyer during the Korean War. He learned from the staff and the patients at the North St. Louis clinic where he was a member of the board. He was advised by John B. Ervin who, following a career at Harris-Stowe Teachers College, had come to Washington University as dean of continuing education. And as chancellor, Bill recognized the unique gifts of James E. McLeod and made him, first, his trusted adviser and then the instrument for transforming Washington University’s undergraduate ethos. Bill was never an outstanding orator, but he was the most eloquent listener I have ever known.

We, the entire Washington University community, did get better under Bill’s leadership, because he imagined (most of us were harder to convince) that we were a community, and he believed that we were better, or at least could be better, if together we tried to be. And during the 24 years of his stewardship, we did improve, slowly and incompletely, but we improved.

McLeod was doing something extraordinary in the college, shifting it from an often cutthroat individualism to a community model, one in which each person does better when all do better. Collaborations between schools and disciplines became more frequent, leading to innovations in both research and teaching.

Bill, with [his wife] Ibby’s constant encouragement, found quiet work the most enjoyable part of his job. Bedtime stories in the dorms, unannounced visits to ailing faculty or just walks around campus (his ungainly form and shyly smiling face a source of surprising warmth in a world where leadership is often cold and remote) were customary. He appeared at football games when attendance was so scant we needed only a single section of bleachers. He showed up at faculty readings and lectures, a man of great natural reserve going to great lengths to be among us. And that us was becoming more complete. The student population became more diverse, less monochromatic, and culturally and intellectually more interesting and accomplished. More women and minorities joined the faculty.

Our diseases were not cured during Bill’s watch, but we began to better understand their pathologies, began to recognize that health was the consequence of wholeness, inclusion was an essential part of wellness. We began to better understand that we needed each other — schools, disciplines, students, faculty — and derived our integrity and much of our purpose out of association with one another.

Whatever his and our faults, whatever the limits of Washington University’s accomplishments in the second half of the 20th century, Bill Danforth gave us the confidence to move forward; he helped lay the foundation for a university deserving of the trust a free people necessarily place in it. Bill loved the idea of a university, the monumental presumption about humanity and learning it represents. And that love is where we must, in every age and in every circumstance, begin.

— Wayne Fields is the Lynne Cooper Harvey Chair Emeritus in English and is a renowned author and expert on American presidential rhetoric and political argument. He received the university’s honorary doctorate of humane letters in May 2019. He is the author of several books, most notably What the River Knows: An Angler in Midstream (Poseidon Press, 1990).