More than 13% of women and 3.6% of men on college campuses have an eating disorder of some kind, but fewer than 20% of those affected ever receive treatment due to lack of available clinicians and the stigma associated with seeking help. New research led by eating disorders experts at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates a phone app may help change that.

In a study involving nearly 700 women on 27 U.S. college campuses, including Washington University in St. Louis, the researchers determined that a phone-based app that delivers a form of cognitive behavioral therapy was an effective means of intervention in addressing eating disorders. Those who used the app reported a decline over time in symptoms, including binge eating, purging, using diuretics, and concerns about weight and shape, as well as improvements in depression and anxiety, which often accompany eating disorders.

The findings are published Aug. 31 in the journal JAMA Network Open.

“College students are busy and often don’t have spare time to seek the help they need, and many college counseling centers aren’t equipped with clinicians who are trained in treating eating disorders, so we believe digital interventions like this one can dramatically increase access to care,” said first author Ellen E. Fitzsimmons-Craft, assistant professor of psychiatry. “In our study, this digital phone app was associated with dramatic increases in access to treatment. And in cognitive behavioral therapy, we know the app is providing a therapy that’s proven to help.”

The study focused on women on college campuses via a questionnaire that evaluated whether each woman was at risk for an eating disorder, such as binge eating disorder or bulimia nervosa. It did not include women with anorexia nervosa because they are more likely to benefit from a different treatment approach.

Once a participant was determined to have or to be at risk for binge eating disorder or bulimia, she was randomly assigned to receive cognitive behavioral therapy through a mobile app or to be referred to typically prescribed care provided through the university’s counseling services. Of the 4,894 women who were screened, 914 were eligible for the study. Of those, 690 agreed to participate, with 385 randomly placed in the group using the phone app and 305 assigned to standard care.

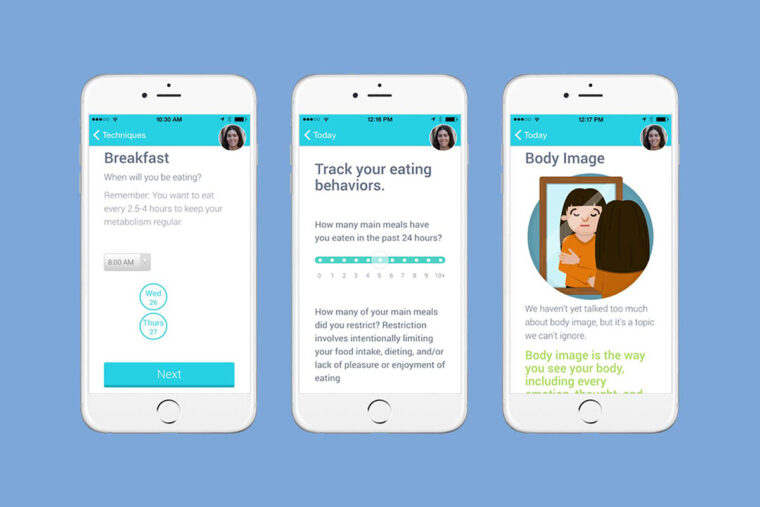

Women who were randomly assigned to use the cognitive behavioral therapy app had access to content that was designed to help them challenge and change unhelpful ways of thinking and behaving. The app also provided participants with the support of a coach, who sent text messages to help the participants stay motivated to use the program and apply concepts they were learning through the app to their daily lives.

“One striking finding was that so many women assigned to the digital intervention actually used the phone app, and it helped to reduce their symptoms, such as marked concerns about their shape and weight, body esteem issues, and binge eating or purging,” said principal investigator Denise Wilfley, the Scott Rudolph University Professor of Psychiatry, who led the study along with co-principal investigator C. Barr Taylor, MD, an emeritus professor of psychiatry at Stanford University and research professor at Palo Alto University.

Study participants who were randomized into the group that used the mobile app were able to engage with the therapy on their own time, according to their own schedules, with therapy broken into a series of 40 sessions, each one about 10 minutes long. Each woman also had access to phone calls with therapy coaches at the start and conclusion of the intervention, as well as text-based communication with them throughout the program.

Part of the phone app’s success in engaging participants was due to the students being more likely to use the app than to pursue and follow up with in-person counseling. Some 83% of those who were randomly selected to use the app completed at least some of the program, whereas 28% of the students assigned to usual care reported receiving any treatment at all. On average, those who used the app completed about a third (31%) of the app-based therapy sessions but still showed signs of improvement when examined during follow-up visits.

When the study began in 2014, the researchers used a more traditional, web-based intervention that involved longer sessions every week. But the researchers soon realized that relatively few of the women were completing those online therapy sessions, so they enlisted the help of a private company, Lantern, to help create the phone-based app. Then they divided up the treatment into a larger number of shorter sessions.

“Students have greater and greater expectations of their technology,” said Fitzsimmons-Craft. “After a slow start with the online therapy, we found that engagement increased significantly once we switched to shorter sessions using the mobile app.”

The researchers also found that women using the phone app experienced improvements in depression and anxiety that often accompany eating disorders. Such interventions may be especially important on college campuses during the COVID-19 pandemic, explained Wilfley, also a professor of medicine, of pediatrics and of psychological and brain sciences and director of the Center for Healthy Weight and Wellness.

“Students with eating disorders tend to isolate themselves socially, but now all students are charged with keeping themselves socially distant,” she said. “There are data showing increases in symptoms of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa now that people are more isolated, with easier access to food and, obviously, unprecedented stress. We think these problems could increase in the coming months, so it’s important that there be ways to reach students who are having difficulty. We believe delivering therapy with a phone-based app may be truly effective.”