In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court ruled Monday that states can require presidential electors to back their states’ popular vote winner in the Electoral College. While the decision limits the independence of electors and prevents a potential source of uncertainty in the upcoming presidential election, it contradicts the Constitution framers’ intentions for the Electoral College, according to a political science expert at Washington University in St. Louis.

“By all contemporaneous accounts, the framers’ whole point was to have the electors decide their own votes,” said Randall Calvert, the Thomas F. Eagleton University Professor of Public Affairs and Political Science in Arts & Sciences.

The Electoral College system has always skewed power in presidential elections toward smaller states, due to the disproportionality of awarding each state a number of electoral votes equal to its number of representatives (proportional to population) plus senators (two per state). However, this may have been a necessary compromise to get agreement to the Constitution in 1787, Calvert explained.

“At the framing, however, the more important consideration was that electors, expected to be more knowledgeable and responsible, would actually do the choosing. Of course, under the system that rapidly emerged — in which electors are selected so as to have no autonomy — this reason became totally irrelevant, and it’s precisely that aspect of the Electoral College system that the court upheld today,” he said.

“One might well argue that today this would be a crazy system that could result in a disastrous or publicly unacceptable outcome. But the idea that conservative devotees of ‘original meaning’ would take this position today is pretty amusing. Well, as Chief Justice [John] Roberts said in last week’s opinion striking down the Louisiana abortion restrictions, they nevertheless have to give precedent its due (in the ruling, justices cited the 1952 Ray v. Blair opinion).”

According to Calvert, so called “faithless electors” never actually have been a problem in practice. However, there is always the danger in a very close election where, in terms of electoral votes, a “faithless” elector might change the election outcome.

“I suspect the real worry was the mess it could make, in the view of today’s public, if ‘faithless electors’ actually change the outcome. The justices wanted to get that danger out of the way as soon as possible rather than have to do it after the election result is known.”

Randall Calvert

“I suspect the real worry was the mess it could make, in the view of today’s public, if ‘faithless electors’ actually change the outcome,” he said. “The justices wanted to get that danger out of the way as soon as possible rather than have to do it after the election result is known.”

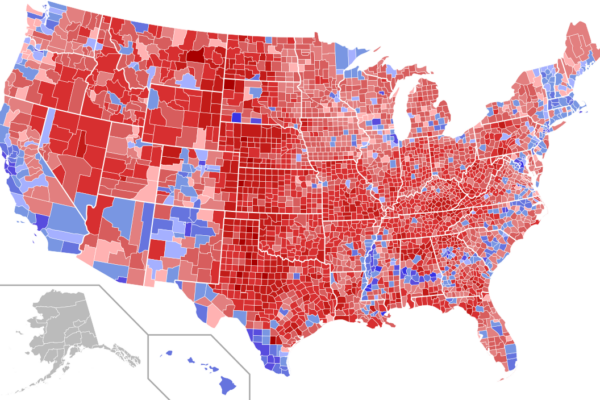

The 2020 presidential election could be a close call, Calvert said. If that happened, public acceptance of the outcome would be doubtful. “Suppose both candidates were to fail to achieve the required electoral majority. The choice then goes to the U.S. House of Representatives, which is required to choose by a system in which each state gets one vote. In all likelihood, and as at present, the majority of House seats will be held by Democrats, but the majority of state delegations will be Republican.”

Usually, the winner of the popular vote also wins the Electoral College vote. Twice in the past two decades, however, that was not the case. Donald Trump got nearly 3 million fewer votes than Hillary Clinton, but won more Electoral College votes and the presidency. In 2000, George W. Bush also beat Al Gore in the Electoral College count, despite not winning the popular vote. Both instances have led to calls to change the way in which we elect presidents.

“A direct election system would require us to set up a new system for official counting of votes nationally, which doesn’t already exist; but other countries seem to pull off that trick without a problem. It would seem the best solution,” Calvert said. “Or, at least, we could require states to allocate their electors proportionately instead of winner-take-all, which, given today’s Supreme Court decision, would make electoral-popular vote mismatches much less likely.

“The greater problem is that either change would require a constitutional amendment, including ratification by three-fourths of the states — and those who get extra electoral votes compared to population are often not interested in changing the system.”

Another proposed solution is the movement for a “National Popular Vote” agreement among the states. Under this agreement, the states would commit themselves, by state law, to allocate their pledged electoral votes to whichever candidate wins the plurality of votes nationally, provided a sufficient number of other states do the same.

“There are several practical problems with that — not least of which is that it could only ever give a different outcome from the current system if some state consented to give all its electoral votes to a candidate who did not win the plurality in that state. I’m skeptical,” Calvert said.