For more than a decade, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has led an international effort to better understand Alzheimer’s disease by studying people with rare genetic mutations that cause the disease to develop in their 50s, 40s or even 30s. The researchers have shown that the disease begins developing two decades or more before people’s memories begin to fade, as damaging proteins silently accumulate in the brain.

Now, the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has committed $29 million to support the effort – known as the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) – for another five years, pending availability of funds. With the new funding, the network will add three new research initiatives to investigate more closely the changes that occur in the brain as the disease develops, which could lead to new ways to diagnose or treat Alzheimer’s.

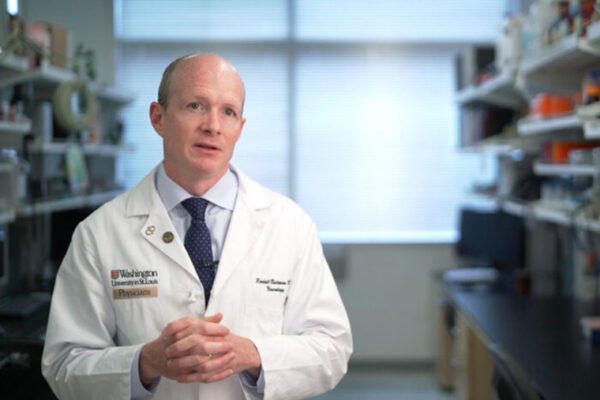

“The extraordinary accomplishments of the DIAN investigators and participants over the past decade have set the stage to understand the molecular changes that can cause Alzheimer’s disease,” said DIAN director Randall J. Bateman, MD, the Charles F. and Joanne Knight Distinguished Professor of Neurology. “The three new scientific projects will provide deep insights into how Alzheimer’s disease begins and progresses to dementia.”

DIAN follows families with genetic mutations that all but guarantee that those who inherit the mutations will develop Alzheimer’s disease at young ages. While devastating for families, this genetic form of Alzheimer’s disease creates a rare opportunity for researchers to look for brain changes – long before symptoms appear – in people who carry such mutations, compared with their relatives who don’t have the mutation.

Although the study follows only people with a rare genetic form of Alzheimer’s, its findings could apply to the millions of people living with the much more common late-onset Alzheimer’s, which appears after age 65. The brain changes that lead to memory loss and confusion are thought to be much the same in early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s.

Since the network was established in 2008, DIAN researchers have established 19 sites in eight countries – representing North and South America, Europe, Asia and Australia – with another five sites in four Latin American countries in the works. People from families with genetic forms of Alzheimer’s take part in observational studies to track changes to their brains over time. The network also has established a clinical trials unit to test investigational therapies to prevent or treat the disease.

Participants undergo assessments of their memory and thinking skills, provide DNA for genetic analysis, undergo brain scans, and give blood and cerebrospinal fluid so researchers can look for molecular signs of Alzheimer’s disease. With the help of such participants, researchers have begun to piece together a timeline of the brain changes that culminate in cognitive decline and dementia. First, the protein amyloid beta starts forming plaques in the brain up to two decades before symptoms arise. Later, tangles of tau protein form, and the brain begins to shrink. Only then do signs of confusion and forgetfulness appear.

In addition to supporting ongoing research efforts, the grant funds three new projects:

- Celeste Karch, assistant professor of psychiatry at Washington University, will lead an effort to study how Alzheimer’s mutations affect the many forms of amyloid beta that can be present in a person’s brain, and how the different forms relate to the development of disease. The goal is to determine whether there’s a harmful amyloid beta “signature” that predisposes the brain to Alzheimer’s.

- Brian Gordon, assistant professor of radiology at Washington University’s Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, and colleagues will assess whether positron emission tomography (PET) tracers designed to detect tau are sensitive and specific enough to track its spread through the brain. The proliferation of tau is closely linked to brain damage and cognitive decline, so understanding how and when the protein spreads could help researchers design clinical trials aimed at preventing or halting cognitive decline. To identify how tau spreads and changes during the course of the disease, Gordon and colleagues also will measure the protein in the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord, and in neurons from stem cells made from DIAN participants.

- While amyloid beta and tau have long been recognized as crucial elements in the development of Alzheimer’s, a growing body of evidence suggests that inflammation and injury to the synapses – the junctions between two neurons – also play a role. Anne Fagan professor of neurology at Washington University, and Allan Levey, MD, PhD, a professor and chair of the neurology department at Emory University, will investigate molecular signs of inflammation and synaptic injury, and determine whether such molecular signs are indicators that the disease is progressing.