More than 60% of women will experience a urinary tract infection (UTI) at some point in their lives, and about a quarter will get a second such infection within six months, for reasons that have been unclear to health experts.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have discovered that an initial infection can set the tone for subsequent infections. In mouse studies, the researchers found that a transient infection triggers a short-lived inflammatory response that rapidly eliminates the bacteria. But if the initial infection lingers for weeks, the inflammation also persists, leading to long-lasting changes to the bladder that prime the immune system to overreact the next time bacteria find their way into the urinary tract, worsening the infection.

The findings, published Aug. 20 in eLife, suggest that reversing such changes to the bladder may help prevent or mitigate future UTIs.

“Millions of women suffer from recurrent bladder infections, and it can really take a toll on their quality of life,” said co-senior author Thomas J. Hannan, DVM, PhD, an instructor in pathology and immunology. “In the process of fighting these infections, the immune system sometimes does more harm to the bladder than to the bacteria. If we could fine-tune the immune response to keep the body focused on eliminating infecting bacteria, we might be able to reduce the severity of these infections.”

To understand why some people are more prone to severe, recurrent infections than others, Hannan and co-senior author Scott J. Hultgren, PhD, the Helen L. Stoever Professor of Molecular Microbiology – along with co-first authors Lu Yu and Valerie O’Brien, both graduate students who have since earned PhDs when the work was conducted – infected a strain of genetically identical mice with E. coli, the most common cause of UTIs in people. The strain can have widely divergent responses to bacterial bladder infections. Some eliminate the bacteria within a few days; others develop chronic infections that last for weeks.

The researchers infected these mice with E. coli, monitored them for signs of infection in their urine for four weeks, and then gave them antibiotics. After giving the mice a month to heal, the researchers infected them again. For comparison, they also infected a separate group of mice for the first time.

All the previously infected mice mounted immune responses more rapidly than the mice infected for the first time. The ones that had cleared the infection on their own the first time around did so again, eliminating the bacteria even faster than before. But the mice that failed to clear the infection the first time did much worse, despite the speed of their immune responses. A day after infection, 11 out of 14 had more bacteria in their bladders than they had started with, and many went on to again develop chronic infections that lasted at least four weeks.

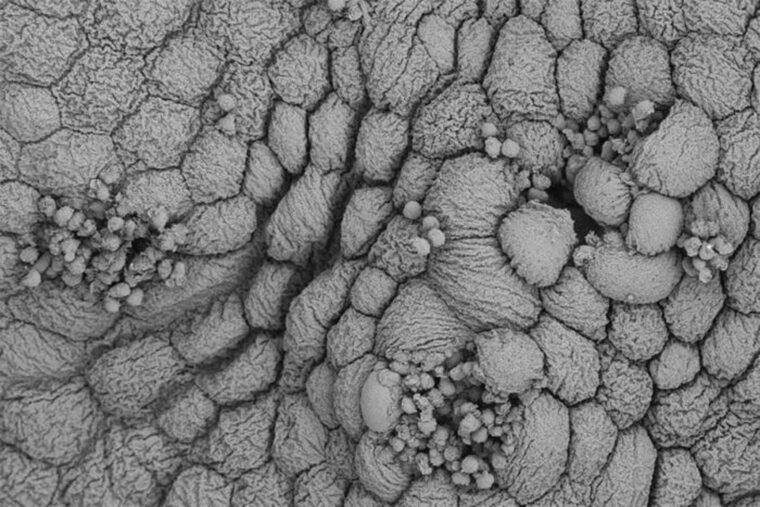

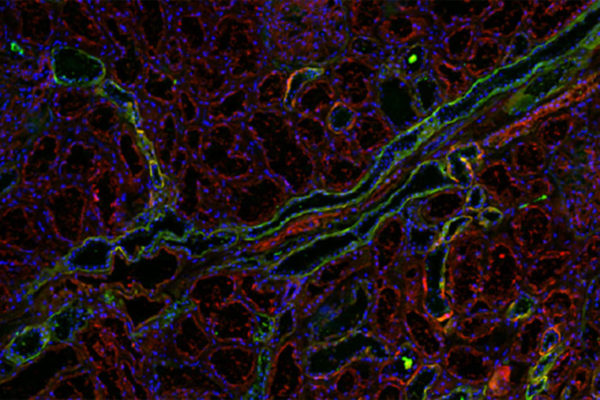

The difference lay in an immune molecule called TNF-alpha that coordinates a powerful inflammatory response to infection, the researchers discovered. Both sets of mice turned on TNF-alpha within six hours of infection. But the mice that controlled the infection turned off TNF-alpha again within 24 hours, allowing the inflammation to resolve. In the mice with prolonged initial infections, TNF-alpha stayed on, driving persistent inflammation and triggering a change to the patterns of gene activity in immune cells and the cells of the bladder wall.

“After a chronic infection, even though the bacteria have been eliminated with antibiotics and the bladder lining has healed, the behavior of cells lining the bladder do not revert back to normal even after the inflammation is finally resolved,” Hannan said. “The bladder becomes trained to respond to infecting bacteria too harshly, causing tissue damage that predisposes to recurrent infection. So then the question becomes, ‘Can we retrain these bladders to be more predisposed to resolving inflammation quickly?’”

To find out, the researchers took mice that had recovered from initial prolonged UTIs and depleted their TNF-alpha before re-infecting them with bacteria. Without TNF-alpha driving excessive inflammation, the mice fared better, significantly reducing the number of bacteria in their bladders within a day of infection.

The findings suggest that targeting TNF-alpha or another aspect of the inflammatory response that causes bladder tissue damage during acute infection may help prevent or alleviate recurrent UTIs, the researchers said.

“Improving our understanding of this underlying biological process will be essential for developing new therapies that target inflammation as an alternative strategy against rapidly increasing antimicrobial resistance,” Hultgren said.