A common assumption is that stock analysts gather earnings and other pertinent information to communicate to current and potential stockholders, and then incorporate that information by revising their current-quarter earnings forecasts.

So much for that perception. A new study, involving two Washington University in St. Louis faculty at Olin Business School, finds that analysts disseminate earnings news by revising share-price targets or stating they expect firms to beat earnings estimates, often tempering such information — even suppressing positive news — to facilitate beatable projections.

The study discovered that, when it comes to the current-quarter earnings reports that are analysts’ most closely followed work product, analysts become selective about which forecasts they update and what information they convey. The researchers found that later forecasts issued by the same analyst — such as share-price target revisions, forecast revisions to the other quarters’ forecasts or textual statements about earnings after the last quarterly forecast — surprisingly predict errors in the analyst’s own current-quarter forecast. These associations are much stronger for good news, consistent with analysts catering to managers’ desires to meet or beat earnings forecasts.

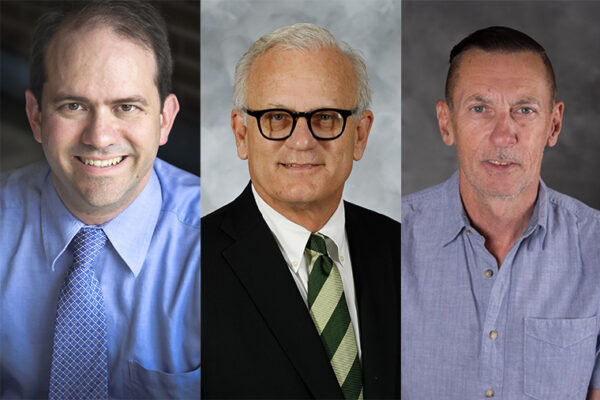

Their paper — co-authored by Zachary Kaplan and Chad Ham, both assistant professors of accounting at Olin, along with Philip Berger of the University of Chicago — is scheduled for the March issue of The Accounting Review.

Using data from 8,860 analysts covering 7,933 unique companies over 71 quarters, the researchers reported the likelihood of a downward revision of current earnings estimates came at a 50-percent greater possibility than an upward revision: 19.5 percent downward vs.13 percent upward. When it came to revising stock-price targets and future-earnings estimates, however, the reverse was true to a 20-percent greater possibility: 11.2 percent upward vs. 9.3 percent downward. The firms most likely to meet or beat earnings were those with positive price-target revisions, suggesting those revisions were at least partially motivated by prior omitted earnings information.

There are two important takeaways from these findings, Kaplan and Ham said.

First, one of the reasons managers are so successful in meeting or beating earnings forecasts is that they persuade analysts to omit positive news from forecasts.

“Managers care a lot about beating earnings forecasts, and analysts rely a lot on managers, so upsetting them is not really an option,” Kaplan said. “Additionally, analysts care deeply about conveying information to their clients, so they cannot merely issue beatable forecasts. The way we find analysts deal with this dilemma is by conveying positive news through the text of their reports and share-price target revisions — this allows managers to meet or beat estimates while also allowing the analyst to update clients about positive news.

“Non-clients, who rely on earnings forecasts because they do not have access to the whole of an analysts’ work product, end up with skewed information, but this is not an issue for the analysts’ business,” Kaplan said.

The researchers said that analysts purposefully lower, or “walk down,” projections. By keeping earnings forecasts low and neglecting some positive developments, the researchers wrote, analysts “cater to managers’ preferences for a walked-down (earnings) forecast pattern. The pattern we document, however, includes avoidance of walking up rather than only a walk-down. … Non-earnings forecast signals are more prevalent for positive news than negative news, consistent with analysts responding to incentives to issue [earnings] forecasts managers will meet or beat.”

Second, by not disseminating all information through current quarter’s earnings forecasts, which are widely available through commercial databases, analysts provide an advantage to clients who have paid for access to the full breadth of their research product.

“Analysts convey information in ways that enable them to be of service to clients, who they care about, and, at the same time, to avoid displeasing corporate managers, who they also care about,” Ham said.

The study may offer a lesson to the broader public: Perhaps widely circulated earnings forecasts aren’t as informative as people think. If you want the best information an analyst has to offer, you have to pay for it.

In a separate survey of brokerages’ reports to clients, the researchers learned that — without changing forecasts — analysts didn’t refrain from explicitly predicting firms would beat or miss their targets … and the “beat” or positive predictions outnumbered the “miss” or negative predictions by roughly 30 percent.