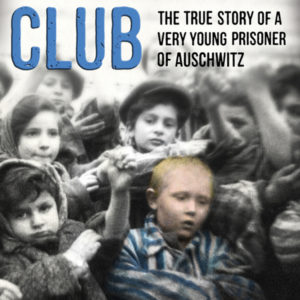

There is a haunting photograph of young children taken by Russian soldiers when they liberated Auschwitz in 1945; upfront in the photo, there is a little blond boy. Just 4 years old, the boy was among the youngest to survive the notorious Nazi death camp. More than 72 years later, the survivor, Michael Bornstein, visited Washington University to deliver a very personal and poignant Assembly Series presentation and discuss his 2017 best-selling memoir, Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz.

Accompanying Bornstein to the Danforth Campus was his wife, Judy, and two of his four children, both Washington University alumnae: broadcast journalist Debbie Bornstein Holinstat, AB ’96, who co-authored Survivors Club; and Lori Bornstein Wolf, AB ’91, JD ’94, an attorney specializing in estate planning.

“There’s been a rise in anti-Semitic bullying in schools, and swastikas have been appearing on synagogues. Muslim-Americans are being harassed, Hispanic-Americans and Blacks are being disrespected. We’ve all heard the stories. I just can’t stay silent any longer.”

Michael Bornstein

Nancy E. Berg, chair of the Department of Jewish, Islamic and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures and professor of Hebrew Language and Literature in Arts & Sciences, introduced the lecture; then Bornstein Wolf introduced her father. Accompanied by his other daughter, Bornstein Holinstat, Bornstein took the lectern and prefaced his gripping saga by noting recent assaults on American democratic values.

“There’s been a rise in anti-Semitic bullying in schools, and swastikas have been appearing on synagogues,” Bornstein said. “Muslim-Americans are being harassed, Hispanic-Americans and Blacks are being disrespected. We’ve all heard the stories. I just can’t stay silent any longer.”

This speaking out represented a radical departure for Bornstein, 77, who had chosen for most of his life not to dwell on the horrific circumstances that led to his being separated from his family and imprisoned at Auschwitz at such a young age. That he survived several months, when the average life span of a child held captive there was two weeks, was extraordinary — and the first hint of a remarkable life ahead for this child born in Zarki, Poland, during the Nazi takeover.

Shared alarm

Bornstein’s fear of growing anti-democratic forces in his chosen homeland were echoed coincidentally just a few weeks later, when a piece was published Dec. 9 in Huffpost to warn Americans of the danger of political complacency. The core message, in today’s parlance, was to “stay woke,” and it was delivered by one of the most politically astute Americans living today: former President Barack Obama.

“It’s not that democracy is fragile, exactly, but it is reversible,” Obama stated. He took the opportunity to remind us that one need only consider what happened in Nazi Germany to understand how the erosion of values and institutions that make up a democracy — notably freedom of religion and freedom of the press — can quickly lead to its disintegration.

“Don’t underestimate the very simple act of being engaged, paying attention and speaking out,” Obama said.

A yearning to know

For Bornstein, choosing not to speak about his past came about not from denial or fear, but because he drew strength from looking ahead. That optimism, an insistence of a better future, got him through a lifetime of struggles.

“Growing up, my father would never talk about his past,” explained Bornstein Holinstat, “partly because he wasn’t the type of person to dwell on his tragic past and partly because he was too young to trust what he thinks he remembered.”

Her father concurs: “My memories from that period come in and out like a cascade of images, some are clear, some fuzzy.” When his daughter would ask him a direct question, he would often answer: “I don’t know … I was really young. I’m not always sure how to separate what I remember from what I think I remember.”

They yearned to know the whole story, not just that of their father, but of their grandparents and great-grandparents and great-aunts and great-uncles — after all, that was part of their story, too.

But throughout the Bornstein home, Holocaust stories were recounted, mostly in hushed voices mumbled among adults in other rooms, out of earshot of the children. Yet pieces of stories emerged about the children’s father and the loving family members who had perished, which only fed the children’s curiosity. They yearned to know the whole story, not just that of their father, but of their grandparents and great-grandparents and great-aunts and great-uncles — after all, that was part of their story, too.

This yearning to know was especially strong for Bornstein Holinstat. And when she took a journalism course in University College, it unleashed that desire to hear and tell people’s stories, borne from her own personal longing. The class led to an internship at KSDK-TV, the local NBC affiliate, which then led to a CNN internship that clinched her decision to enter the journalism profession. After graduation, she filled that need by writing and producing segments for NBC and MSNBC News, putting together other people’s stories for mass consumption. It was at this juncture that she put the bug in her father’s ear to write a book. His response? “I don’t know, Deb — maybe someday.”

Above all, Bornstein loved his family and hated disappointing his children. However, the desire to keep looking forward was ingrained, even as he headed into retirement after a long, successful career as a research scientist. Why dredge up gruesome memories now, he reasoned, especially since his children were grown and had their own families?

He had deliberately kept the ghosts of his past locked away, hoping to spare them all from unhappy thoughts. What good would it serve, for example, to recount his nightmare on the first night after liberation, the one that continued to haunt him for years to come? He recounts in his book:

“I had a terrible dream that night … In this dream, Mamishu was going into the big building at Auschwitz where so many people lined up to enter — naked, compressed together like one mob of ribs and skin. On the other side, Jewish laborers shoveled out limp, dead bodies as fast as they could. In the dream, Mami’s corpse went through a big machine that turned her into soap. Then I was in the machine, and I was being smashed between giant rollers. All the bones in my face and then in my stomach were shattering into a million tiny fragments, and my skin was melting. I was turning into soap, too.”

Bornstein Holinstat resolved to leave it alone, so she was shocked when, nearly 70 years after her father had been liberated from Auschwitz, he came to her and asked for her help in writing his memoir.

“I slammed my computer shut in disgust. I was horrified. It made me realize that if we survivors remain silent — if we don’t gather the resolve to share our stories — then the only voices left to hear will be those of the liars and the bigots.”

Michael Bornstein

A trip to Israel in 2013 had changed his mind. Visiting the Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Museum in Jerusalem, Bornstein saw, for the first time, his image in the now iconic photo (the one on the book’s cover) of children being liberated by Russian soldiers. Sometime later, he began looking on the Web for similar images. Finding one, he clicked the link and found himself on a website dedicated to denying the Holocaust ever happened.

“I slammed my computer shut in disgust. I was horrified,” he states in the book. “It made me realize that if we survivors remain silent — if we don’t gather the resolve to share our stories — then the only voices left to hear will be those of the liars and the bigots.”

At that time, the immortal words of Holocaust survivor and Nazi hunter Elie Wiesel must have hit home: “For the dead and the living, we must bear witness.”

As one of the youngest to ever bear witness to that horrific episode in history, Bornstein’s life story is a rare gift to his children, his grandchildren and to the world, providing a powerful weapon to defeat the deniers.

Editor’s note: The Nov. 13, 2017, lecture was co-hosted by the Assembly Series, the School of Law and Arts & Sciences.