As President Donald Trump prepares to offer his first State of the Union address, a new analysis by a Washington University in St. Louis sociologist may explain why the pronounced, decades-long expansion of U.S.-based hate groups has slowed to a crawl during the first year of his administration.

“Trump’s election signaled the closing of the perceived threats that drove hate groups to form during the Obama administration and provided a perceived window of opportunity for existing groups and their supporters to act with relative impunity,” said David Cunningham, a professor of sociology in Arts & Sciences.

Trump’s 2016 election campaign took place as the number of extremist hate groups in the nation was reaching near-historic levels. In the 34 days following his election, more than 1,000 right-wing hate incidents were documented by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC).

While it would be easy to conflate these trends, Cunningham’s research showed that there are important differences between factors that spur growth among hate groups and in individual hate crimes.

“My research shows that hate groups tend to grow in response to threats emerging from environments where social groups perceive their standing to be uncertain or at risk,” said Cunningham, an expert on the Ku Klux Klan and other hate-based social movements.

“Hate incidents, in contrast, are most likely to rise primarily in response to expanding opportunities to act. Whether perpetrated through established extremist organizations or by free-standing adherents, such actions are most likely when those who desire to commit them perceive lower costs or risks.”

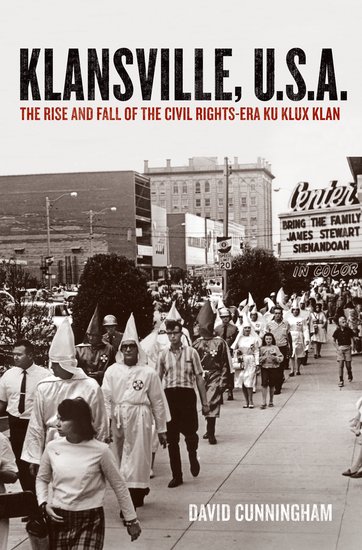

Cunningham is the author of “Klansville, U.S.A.: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-Era’s Largest KKK” (Oxford University Press, 2013), which served as the basis for a 2015 PBS “American Experience” documentary of the same name. His research on the causes and ongoing legacies of racial and ethnic conflict has been supported by the National Science Foundation, the Spencer Foundation and the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation.

In a paper recently published in the journal Sociological Research Online, he used data from the SPLC to illustrate how hate organizations used perceived threats to white supremacy to quietly expand their ranks during the Obama administration, a period when some suggested we were living in a new post-racial America.

As the SPLC data showed, the number of U.S. hate organizations nearly doubled in the past two decades — rising from 457 groups active in 1999 to 917 in 2016. This under-the-radar expansion was fueled, SPLC analysts argued, by two major threats to what they perceived as the traditional white order.

First, the inclusion of a multiracial category in the 2000 Census, which spurred news coverage predicting that whites would, for the first time, be a numerical minority in the nation by 2043; and second, the election of an African-American president, Barack Obama, in 2008.

But these threats began to fade, Cunningham contended, as Obama’s second term wound down and the Trump campaign gathered momentum. As SPLC data again illustrated, the growth in hate organizations had nearly stalled in 2016, even as the nation began experiencing a disturbing surge in hate crimes and incidents.

After decades lurking in the shadows, extreme factions of the alt-right and white nationalist movements viewed the Trump presidency as a “get active” opportunity, launching a fresh wave of anti-immigrant, anti-black and anti-Muslim hate crimes.

“The Trump campaign and presidency has of course created this license,” Cunningham said, noting that more than one-third of post-election hate crimes invoked the president or his campaign slogans.

In the current political climate, the perceived cost of committing hate crimes is lessened by Trump’s consistent unwillingness to condemn the violent acts of white nationalists, he found.

“In short, emboldened white nationalists are drawing on the organizational infrastructure they have developed over the past two decades to more openly advance their agendas,” he said.

Understanding the differing influences of threat and opportunity on hate-group recruitment and hate crimes is important, Cunningham suggested, because it could help policymakers anticipate and deal with hate-based counter-movements and inform efforts to reduce or halt the commission of these acts.

Cunningham’s research also offers hope to people who fear that the hatred and violence displayed at the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Va., is a sign of worse things to come.

As Cunningham’s research on the rise and fall of the KKK in the1960s showed, hate groups whose appeal is rooted in hardline racism and a predilection for violence face an especially difficult balancing act when they aspire to a mass base, as cross-pressures associated with the very source of their appeal can contribute to their undoing.

While threats to white supremacy may serve as an organizational incubator, the paradoxical converse is that in the absence of such threat, extremist organizations can find it difficult to maintain their organizational momentum, even as they gain political momentum. And, as Cunningham discussed in a recent blog post, opportunistic surges in hate crimes and violence may foster further backlash against the movement.

“Rather than a springboard for a white supremacist insurgency, Charlottesville’s ultimate legacy may reside in its sweeping impact on how white nationalist events are countered both by police and by counter-protesters — and thus as the tragic event that slammed shut the alt-right’s window of opportunity,” he said.