Rachel Neff was scrolling through the Washington University School of Medicine website when the word “Ebola” caught her eye. She was reading about the work of Gaya Amarasinghe, associate professor of pathology and immunology who studies how viruses evade our immune system.

The Ebola virus had caused thousands of deaths in West Africa in 2014 and 2015. Neff was fascinated by the possibility of learning how the virus causes disease.

“Rachel emailed me saying she wanted to work on Ebola, and I told her I’d consider it if she could come up with a project,” Amarasinghe said. “Most students lose interest at that point, but she kept on emailing me and emailing me, and finally I agreed to talk to her. She turned out to be a very special student.”

The 18-year-old was enrolled in an independent-study science class at Wentzville’s Holt High School with Jennifer Mallery, a scientist-turned-teacher who guides her advanced students through the scientific process – from idea through experimentation to manuscript writing – over the course of a year.

Amarasinghe helped Neff design a project focusing on a protein called VP35 that is found in both the Ebola virus and the bat genome. The Ebola version of VP35 suppresses the immune response in infected animals, allowing the virus to multiply. Bats are thought to carry the Ebola virus — and transmit it to humans — but are not sickened by it themselves. Scientists are exploring whether VP35 in bats may interfere with Ebola VP35, protecting the bats from disease.

“Her project was one she had to work at,” Mallery said. “She had never done protein modeling before, so she had to learn not just the scientific concepts but how to use the very complicated software, but she just powered through it. It doesn’t matter what you throw her way, she can handle it.”

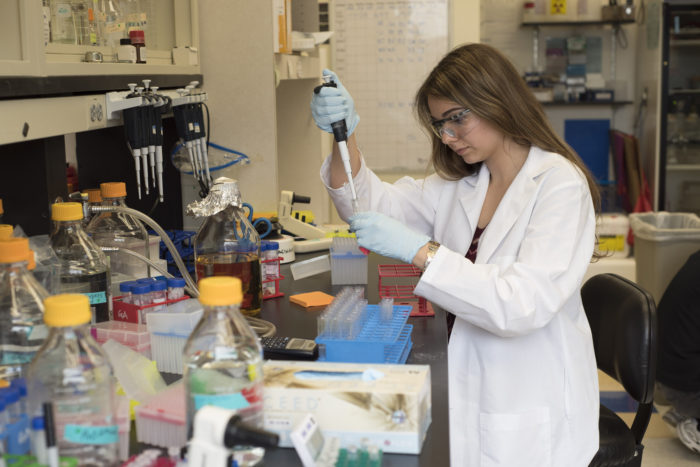

Neff spent three months studying the sequences and structures of the bat and Ebola versions of this protein and designing a mutation to interfere with the protein’s function. Then she produced the mutated protein and showed that it was unable to link up into groups of four, as the protein typically does. Amarasinghe said he believes the protein needs to form groups of four to function, and that without that ability it would not be able to protect bats from disease caused by Ebola virus.

“The ultimate goal would be to test the functional relevance: to mutate the gene in bats and see whether bats with the mutated VP35 would still be protected from Ebola or not,” Neff said. “If the bats get sick, it means that the protein is indeed anti-viral, and we could apply that knowledge to humans. But we are not there just yet.”

Megan Edwards, a postdoctoral fellow in Amarasinghe’s lab, supervised Neff. “I have a hard time remembering that Rachel is still a high school student,” she said. “She is so driven, so independent. You can show her something once and she’ll just run with it.”

Neff submitted her project to the Missouri Junior Science and Engineering for Humanity Symposium at Maryville University, where she placed second, qualifying her to go on to a national competition in Dayton, Ohio. She also competed in the Tri-County Regional Science and Engineering Fair, where she won second place overall, to add to awards from the Air Force and Navy, and from the American Chemical Society.

Neff plans to study biochemistry at the University of Missouri in the fall. In the meantime, she’s working in Amarasinghe’s lab — on proteins from Marburg virus, a relative of Ebola.

“Bringing a student who is so keen on science into the lab and seeing her learn so much is just a great experience,” Amarasinghe said. “Her teacher asked me if I’d be willing to take another high school student next year. I said, ‘If you can get me another Rachel, yes!’ ”