https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LLey2plIZiU&feature=youtu.be

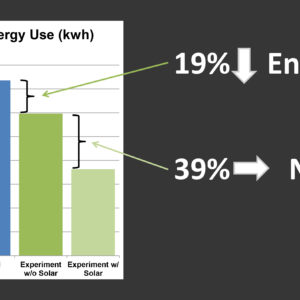

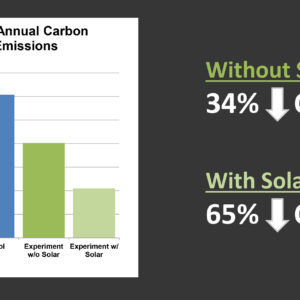

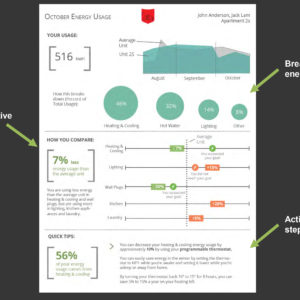

A six-percent upfront investment reduced energy consumption by 19 percent — and carbon emissions by 34 percent — in a pair of 100-year-old brick buildings. Add solar panels, and those numbers drop to 39 percent and 65 percent.

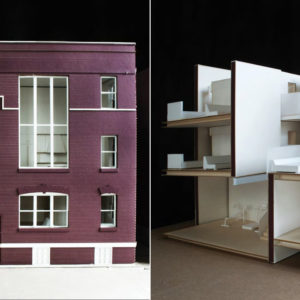

These are among the findings of an ongoing experiment conducted by students, faculty and staff at Washington University in St. Louis. The architectural equivalent of a twin study, the project centered on the gut-renovation and subsequent energy monitoring of two university-owned, World’s Fair-era apartment buildings.

“This was a rare opportunity,” said Phil Valko, assistant vice chancellor for sustainability, who led the project with Don Koster, senior lecturer in architecture in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts.

“Both buildings have the same square footage, the same number of apartments, the same floor plans and the same sun exposure,” Valko said. “That gave us a unique opportunity to design, implement and test real-world strategies for energy-efficient rehab.”

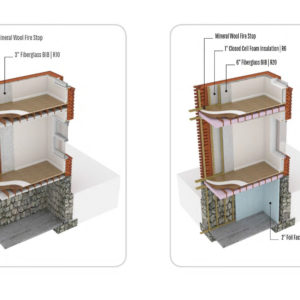

Though they remain virtually identical to the casual observer, the two structures were renovated in subtly yet significantly different ways. For the “control” building, Quadrangle Housing, the university’s property management subsidiary, followed its standard renovation protocols. But for the “experimental” building, Quadrangle implemented recommendations developed through a series of studios open to students in architecture, engineering and construction management.

“In sustainability circles, we often talk about the ‘state of the shelf,’ ” Valko said. “What can you do with existing technologies? Almost everything we used can be found at your local home improvement center.

“The ultimate goal is to chart a path to net-zero energy, but we want the lessons learned to be replicable,” Valko said. “Working within the constraints of the marketplace meant that we had to be very creative with the technologies we selected. We had to find low-cost technologies that offered a lot of ‘bang-for-the-buck.’”

For example, while the control building uses industry standard 13 SEER HVAC units and an electric water heater, the experimental building upgraded to 18 SEER units and a natural gas water heater. Insulation was doubled, from 3 inches in the control to 6 inches in the experimental building, and the standard lighting package was replaced with LEDs. Other differences include specifying Energy Star Certified appliances, and using passive cooling strategies such as casement windows and ceiling fans.

“I think we’ve demonstrated that you, as a building owner, can in fact design an energy efficient building that’s comfortable and modern — and do it affordably,” Koster said.

For a relatively modest budget increase, “you can have a positive impact on carbon emissions and leave society with a better future,” Koster said.