The word “architect” evokes images of a person designing aesthetically pleasing houses, buildings and outdoor spaces. But architects do so much more than make things visually appealing: They build better communities by increasing accessibility, addressing inequities, protecting the environment and improving lives.

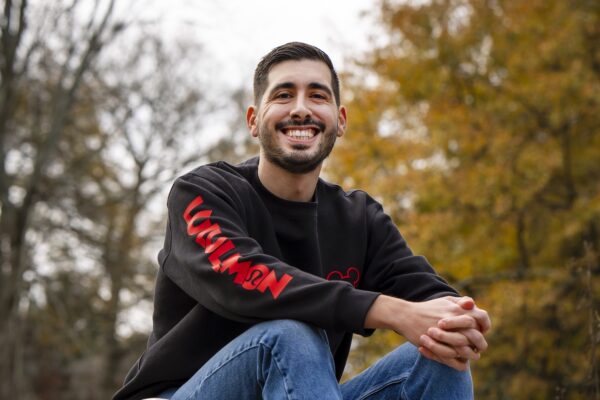

“Architecture,” explains Brendan Wittstruck, MArch ’11, MAUD ’11, MCM ’11, “is a life of service.” A landscape architect and urban designer at Dunaway in Austin, Texas, Wittstruck focuses on incorporating nature into urban spaces.

I wanted to use my undergraduate degree in art to address pressing climate issues. A career in architecture seemed like the best next step to merging my interests in art and sustainability. WashU won me over with its emphasis on community design. But when a good friend at WashU encouraged me to take an urban design intro class, I realized that was the scale of impact I was looking for. Somehow, I ended up being a landscape architect, but I still hang on to a lot of the design training I got in architecture.

Landscape architecture and urban design can positively impact the broader ecology and connect people with green spaces within cities, making these areas more livable. There are so many benefits to integrating landscaping into people’s lives. Trees and other plants improve air quality and local climate. Data shows that green spaces shorten hospital visits and improve moods. And park access is a huge indicator for quality of life in cities.

To make urban areas more livable, we must address inequities. When it comes to public spaces, it’s so important to keep in mind who we’re designing for and make sure we’re not leaving people out. Will this space be comfortable and safe for women? Have we considered the needs of parents? Is there accessibility for strollers? What happens when the “eyes on the street” are prejudiced? Urban design as a practice is rethinking older ideas of environmental design that intentionally and unintentionally excluded many people from participating in the public realm.

Highway removal is another way to improve urban lives. Since I did my thesis on highway removal at WashU, the “freeway fighters” movement has gained momentum. Nationally, there is a striking pattern of highway projects razing and disconnecting communities of color. Highways in cities just don’t make any sense: They take up too much space, cut up neighborhoods, pollute, and can actually make traffic worse. Their purported benefits are completely eclipsed by their negative impacts on the urban environment and surrounding communities.

One of my early projects recently came full circle. Shortly after graduating from WashU, I was part of a design team for the Colony Park Sustainable Community Initiative in Austin, which set 208 acres of city-owned land on a path toward being a mixed-use community. It’s an important effort focusing on bringing basic services and housing to a historically underserved community of color that doesn’t even have a grocery store. I helped develop the sustainability guidelines on this master plan and am now leading the site design of a nature play area for a health clinic there. It’s exciting to be involved with the design of a plan I helped develop over a decade ago!