In 2007, an enormous tornado, the first EF5 ever recorded, struck Greensburg, Kansas. Twelve people were killed. Ninety-five percent of buildings, nearly 1,200 in all, were destroyed or badly damaged.

Today, a rebuilt Greensburg is arguably the most environmentally sustainable town in the United States. The new school, hospital, city hall, arts center and even the John Deere dealership are all LEED-certified — the nation’s highest such concentration per capita. Streetscapes foster walkability, support native plantings and collect storm runoff for irrigation. The city-run electrical grid is powered by windmills.

“Wind decimated Greensburg,” says Patty Heyda, professor of urban design and architecture in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. “Now the wind is being harnessed.”

In Rebuilding the American Town (Routledge, 2025), Heyda and co-author David Gamble, lecturer in urban design at MIT, profile nine small municipalities, all with populations under 50,000, that are meeting local and global challenges with smart, creative and adaptable design.

“Urban studies tend to focus on big cities,” Heyda says. “Small towns get overlooked. But a lot of the American landscape is made up of small towns.”

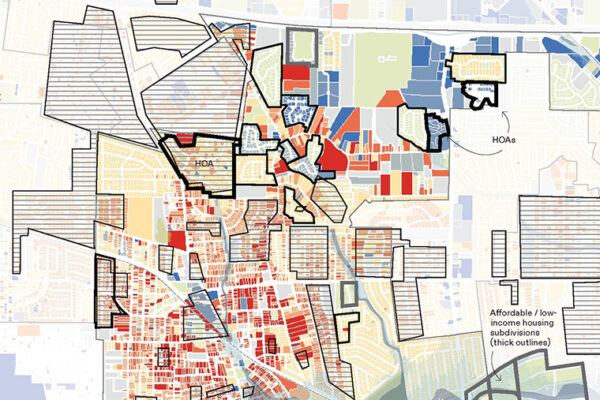

Though towns are frequently characterized in geographic or economic terms — hill town, river town, mining town, farming town — Heyda and Gamble propose alternate typologies, predicated on spatial relationships, in their book. Constellations, for example, are clusters of towns that operate interdependently. Satellites are located on the outskirts of larger metro regions; metroposts are embedded within. Outposts arise independently, with economies typically tied to the land.

“We’re interested in patterns of urbanization and how they differ contextually,” Heyda says. A satellite town and a rural outpost, even of similar sizes, “will have very different dynamics in terms of jobs, population, regional leadership and access to capital.”

In Traverse City, Michigan, an outpost of 15,000 on Lake Michigan’s Grand Traverse Bay, Heyda and Gamble chronicle how a former state hospital was redeveloped into affordable housing — at once preserving a vast historic complex, adding population density and conserving surrounding lands. Caldwell, Idaho — a bustling Boise satellite — created new communal space by restoring Indian Creek, a central waterway long buried beneath downtown streets.

In San Ysidro, California — a metropost squeezed between San Diego and Tijuana — local nonprofits are working to mitigate the spatial, cultural and health impacts of a mammoth, car-dominated border crossing. “It’s a case of urban design and community engagement that’s hyper-local in site,” Heyda says, “but also at the center of global flows.”

Back in Greensburg, tornado recovery was enabled by a sprawling coalition that included farmers, environmental advocates, government officials, local business leaders, impassioned high schoolers, Kansas State student architects, a Discovery Channel film crew, a motorcycling club and the actor Leonardo di Caprio.

For Heyda, the success of that coalition, and its shared sense of purpose, upends assumptions about red-vs.-blue state political divides. “Urban design strategies are not defined by party,” she says. “Greensburg is a small, religious farming community that built back in the most progressive way possible. People there understand the land. They understand responsibility. They understand planning for the future.

“Towns do what they need to do to take care of their people,” Heyda says. “In a small town, there’s a totally different level of accountability. If you implement a new program or policy, you know by name exactly whom it’s going to impact.”