WashU Libraries has received a remarkable gift of 461 letters by the late U.S. poet laureate Howard Nemerov from a surprising source — the family of Nemerov’s lover.

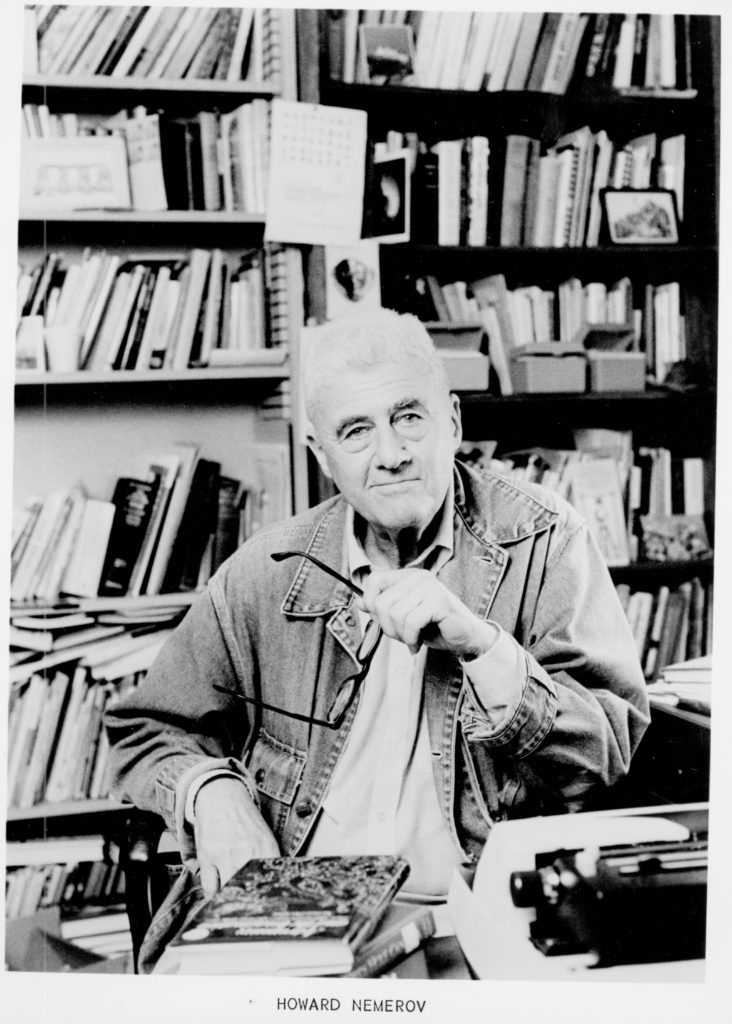

From 1972 to 1990 — a year before Nemerov died of cancer in St. Louis — Nemerov wrote frequent letters to Joan Coale of Philadelphia about his work, family and life on the Washington University in St. Louis campus, where he served as the Edward Mallinckrodt Distinguished University Professor of English and distinguished poet in residence. The correspondence overlaps with a fertile period of Nemerov’s career. His 1977 book, “The Collected Poems of Howard Nemerov,” won the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. And in 1988, he was appointed U.S. poet laureate.

No one knew about the relationship outside of Coale’s family — until December, when Coale’s son, coincidentally named Howard, contacted WashU Libraries’ Joel Minor, curator of the Modern Literature Collection and manuscripts.

“She would say over and over, ‘You know, my letters from Howard must go back to Washington University archives.’ She made that very clear,” said Coale, whose mother died a year ago at the age of 97.

On Feb. 13, Coale fulfilled his mother’s dying wish, presenting the letters — typed on Washington University Department of English letterhead and folded neatly in their original envelopes — to WashU curators and scholars in Olin Library.

Also present: Nemerov’s middle child, Alex Nemerov, the renowned art historian and Stanford professor, who flew from San Francisco for the occasion.

The meeting could have been tense. It was not. Rather, for 90 minutes, the two sons opened up to each other about the relationship and its complicated participants — the literary giant who was self-effacing yet vain, generous but dour, and an artistic woman who was both guileless and sophisticated, strong and acquiescent.

“I don’t necessarily believe in life after death, but I do feel my mother’s joy at these coming here,” Coale told Nemerov. “But maybe your father and my mother have, whether by some mysterious force or by something embedded in our conscience, brought this all together.”

“I think maybe it sounds like you and I, Howard, can readily believe that the dead speak through us,” Nemerov answered. “I just don’t think my dad would give credibility to that himself.”

Howard Nemerov was born in New York in 1920; his younger sister was famed photographer Diane Arbus, who died by suicide in 1971. Nemerov met his wife, Peggy Russell, in England while serving as a pilot in World War II. Together they had three sons. After teaching stints at various Northeast colleges, Nemerov was invited in 1969 to join the faculty at WashU, where he worked alongside other literary luminaries including William Gass, Stanley Elkin and Mona Van Duyn.

As his star rose, Nemerov would travel to conferences and readings where Coale sometimes joined him. Howard Coale is unsure how his mother met Nemerov, but imagines it was at the University of Pennsylvania, where she attended cultural events. Coale didn’t like most of his mother’s suitors, but Nemerov was different.

“When I’d come home from school, if there was a car I didn’t recognize, I would leave. Well, he didn’t have a car, so I walked in, and they were sitting right there,” recalled Coale, also a writer (Nemerov later blurbed his novel, “The Ouroboros.”). “He had a small glass of whiskey, I believe.”

“A martini,” Nemerov suggested.

“Yeah, or a martini,” Coale continued. “And my mother introduced me. I had no idea who he was or what he did, but he seemed like a compassionate person who was very much present. And some of the earlier men my mother dated were obscure scholars in God knows whatever branch of knowledge. And a lot of them were really pretentious, frankly. But I liked him immediately because he had this sense of warmth without being an effusively emotional person. I just liked talking to him.”

Nemerov has a different memory of that time. His father was remote and his mother an alcoholic, deeply traumatized by both the war and her tyrannical mother.

“I have some ambivalence because those years were not very good in our house,” Nemerov said. “My mother had a lot of troubles, some of which were my dad.”

Still, Nemerov said the letters — Minor had sent him a few PDFs — brought him a measure of peace.

“I think I knew he was not faithful,” Nemerov said. “I welcome the information. More than the information, the chance to sort my feelings, I suppose. Reading the letters yesterday, I felt very softened toward the whole thing. I think it’s a chance to reflect and walk the line between a pretty unhealthy, forensic study of one’s own childhood years, and a chance to come more into the realm of the truth, which is always joyous no matter how emotionally complicated.”

Now, Minor must start the long process of digitizing the correspondence. The Libraries’ existing Howard Nemerov Papers contains 257 boxes of correspondences with important literary figures, drafts of poetry, recordings of readings and ephemera from his appearances across the nation. After hearing from Coale, Minor went in search of letters from Joan Coale to Nemerov. Indeed, he found 24 handwritten letters to Nemerov, though clearly she sent many more.

“In later life I am learning not to be embarrassed at what I really feel and this is a great liberation so I am really not embarrassed at being drawn to you,” she writes in one.

Minor said the Nemerov letters he has reviewed thus far are a mix of the mundane, the literary and the romantic. He visits the Missouri Botanical Garden’s Japanese Garden, loses his keys, catches a mild intestinal bug; chafes at higher education’s obsession on all things “innovative” and “interdisciplinary”; and is unhappy with a poem he wrote for The New Yorker.

Throughout, he expresses gratitude for Coale’s love and patience, writing in one letter: “I’ve many times thought, and said to you in letters, that your love for me was an impediment to your chances — career, another marriage, you will remain beautiful longer than anyone — and that I wasn’t doing enough for you, couldn’t do enough for you, to make up the deficit of a serious and settled life both professional and domestic. But there it is, and here we are, a dozen years after the accident that made us lovers.”

Discoveries like this — increasingly rare in this age of texts and email — have much to teach us about the artists we love and the works we treasure, Minor said.

“That first email from Howard — it was a bombshell,” Minor said. “This is what I mean when I tell people you never know who’s going to contact you. It’s the really exciting part of the job. And to witness these two men who knew Nemerov in such different ways talk about their lives and memories, honestly, it is one of the very best days I’ve ever had here.

“Now the scholarship begins,” Minor continued. “What are we going to learn about his outlook on his work and writing in general? What will we learn about his personal history and his outlook on life?”