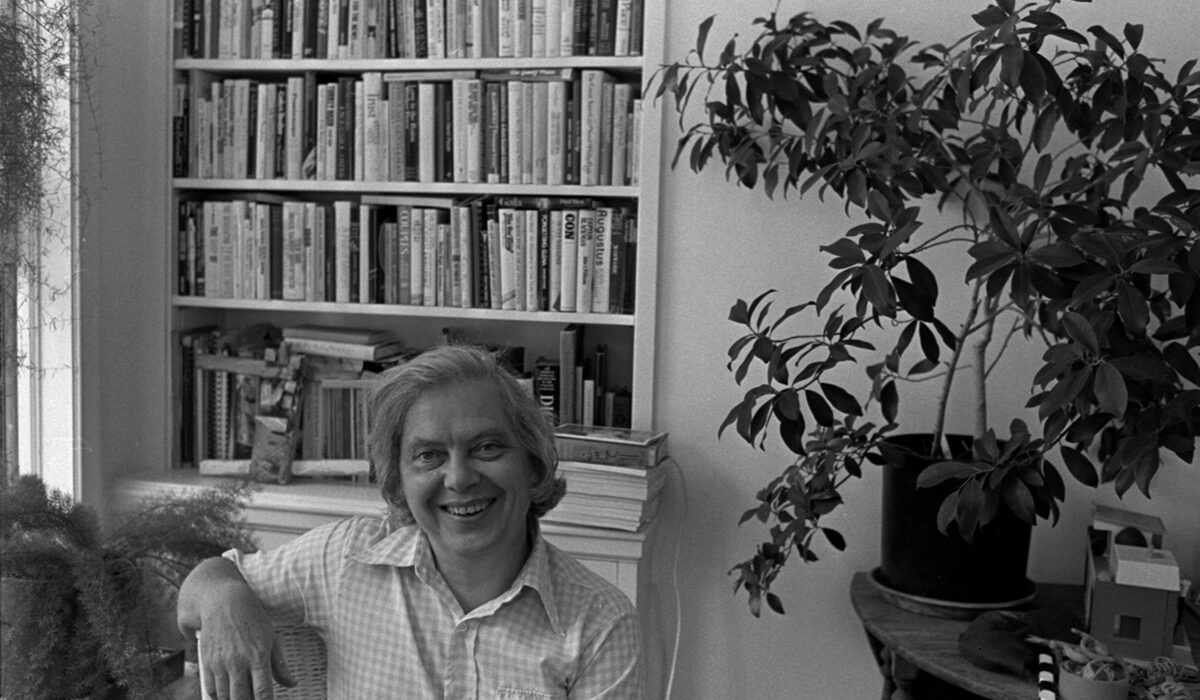

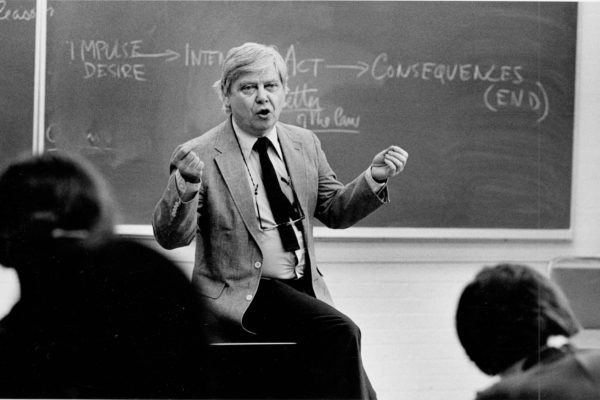

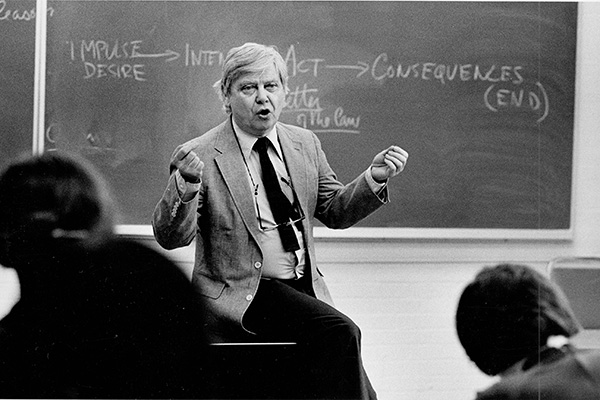

One hundred years ago, one of America’s most innovative and influential novelists was born. He also remains one of the form’s most intimidating. That writer is, of course, William H. Gass, author of numerous short stories, novellas, novels and essays. Gass also taught generations of WashU students as the David May Distinguished University Professor in the Humanities. He died in 2017 at age 93.

“William Gass challenges you as a reader,” said Joel Minor, curator of the Modern Literature Collection at WashU Libraries. “You cannot passively read his work. But while some people find his sentences dense and experimental style off-putting, he is widely admired for the philosophical complexity of his work.”

In celebration of Gass’ life as a writer, critic and educator, WashU Libraries will host the William H. Gass Centenary Celebration from 3-7 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 3, in Holmes Lounge, Ridgley Hall. The event includes a panel discussion with Gass’ former students and colleagues followed by an interview between WashU’s Martin Riker, in Arts & Sciences, and novelist Bradford Morrow, who will discuss his long friendship and professional relationship with Gass. WashU Libraries invites the WashU community to share memories of Gass here. The celebration is free, but participants must register.

WashU Libraries also is hosting the new exhibit, “William H. Gass: Fifty New Acquisitions,” through Jan. 31 at Olin Library. The exhibit builds on “The Soul Inside the Sentence,” WashU Libraries’ 2013 exhibit, which featured published and unpublished writings, recordings, photographs and the essay, “My Memories of the Service,” which Gass wrote specifically for the exhibition.

Here, Minor reveals more about the exhibit and Gass’ lasting impact as a writer and critic.

Tell us more about the new additions to your Gass collection.

Many of the selected items in the new exhibition come from (his widow) Mary Gass, who has continued to generously donate to the collection. That includes a lot of audio tapes of him at events, conferences and during interviews. All of those are digitized and accessible, with excerpts available online. A lot of the recordings are from the ’80s and ’90s, when he was working on “The Tunnel,” which took him three decades to write and is 652 pages long. For Gass fans, there are a lot of new insights in these tapes alone.

As a reader of Gass’ work, what did you learn from the new materials?

It really deepened my understanding of Gass as a writer and his outlook on literature. He’s often categorized as a postmodern writer. But in one interview, he says he doesn’t consider himself or other “postmodern” writers such as John Barth, Robert Coover and William Gaddis to be postmodern. He really saw them all as building upon the modernist approach. Everyone thinks of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” as the ultimate modernist book. Gass was similar in that he packed so much into his fiction. He says on the tape he has a “baroque imagination.” But he was also postmodernist in that his narrators were often interacting with the reader, and not to be fully trusted — the “metafiction” approach, a term that he coined.

Describe some of the other new materials.

There are proofs and drafts of some of his books, including “Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife,” which was an illustrated novella from 1968. That book turned a lot of heads at the time because of its use of photographs and other graphics to depict the narrator, Babs Masters, seducing a new lover — i.e. the book trying to seduce its reader. The designer reached out in 2022 and said he had the first numbered, signed edition, which had been in the vault for over 50 years. He also had drafts and correspondences. We didn’t even know that was out there. For a curator, that’s an exciting part of the job. You never know, day to day, who’s going to get in touch with you with something to add to Special Collections.

Gass is probably more widely known than widely read. Are there some gateway works that you would recommend?

You might call him a writer’ s writer. Literary writers know him and they respect him for the encyclopedic quality of his long novels. But there are works that are more approachable. One fiction collection I would recommend is “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country,” from 1968. Another personal favorite is the novel “Middle C,” which came out in 2013 and is about an immigrant who is a music professor and a fraud. Gass wanted to be known for his fiction, but he wrote many more essays than stories, publishing nine volumes of nonfiction. His essays are about literature but also philosophy, architecture, photography and society. Gass actually won three National Book Critics Circle Awards for his criticism, still a record. Actually, most of all I would recommend “The William H. Gass Reader,” which he and Mary compiled shortly before his death and includes a wide sampling of both his fiction and nonfiction. It was published by Knopf in 2018.