On the first day of class, Elinor Harrison, AB ’01, PhD ’18, asks her students to think about the primary purpose of the brain. “Cognition? Perception? Motor learning? Emotion?

“Of course, that’s a trick question,” she says. “There’s no real way to separate these phenomena. They are all integral to the human experience.”

Harrison is discussing her class “The Neuroscience of Movement: You Think, So You Can Dance?” First offered in 2020, and cross-listed in performing arts, biology and philosophy-neuroscience-psychology (PNP), all in Arts & Sciences, the course draws on Harrison’s experience as a professional dancer and as a research scientist who studies movement therapies.

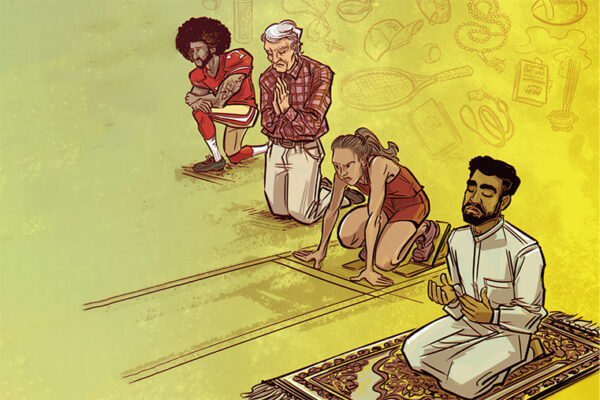

“We usually have more non-dancers than dancers,” Harrison says. “But almost everyone’s had the experience of practicing some kind of skilled movement, whether that’s in the studio or recital hall or baseball field or tennis court.

“This class does not require any particular training or level of motor skill,” she says. “We all have a range of abilities. Every student brings with them a wealth of embodied knowledge that only they possess. So how can that experience be applied to the ways we think about science?

“The goal of this class is to not only critically evaluate scientific literature,” she adds, “but to generate new scientific questions.”

Sensory information

Part lecture, part studio, “The Neuroscience of Movement” meets in Seigle Hall with regular excursions to rehearsal spaces in Mallinckrodt Center and the Anne W. Olin Women’s Building.

“I don’t believe it’s particularly useful to learn the neuroscience of movement by sitting still,” Harrison says with a smile. “Walking by my classroom, you might see students improvising dances, balancing on foam blocks with their eyes closed, or walking in circles clapping and singing.”

If that sounds fun, it is. But the pedagogy is strategic. Dancing with partners, tumbling on the floor, tossing tennis balls back-and-forth — such activities build camaraderie and combat self-consciousness. They also underscore import concepts like kinesthesia, proprioception and the role of the brain in navigating space.

“We move through the evolutionary basis of movement — how our nervous systems evolved to integrate sensory information, how action and perception give rise to consciousness, how complex neural processes allow us to coordinate our bodies in space and time,” Harrison says. “And that lays the foundation for dance and music, which are both fundamental functions in human society.

“Dance and music exist in every culture that we know about,” she adds. “Our brains must have evolved to enable these skills for a reason.”

Perception and movement

For their midterm project, students critically evaluate existing literature on one of six movement disorders: Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, stroke and spinal cord injury. “Sometimes students have a loved one with one of these disorders,” Harrison says. “Sometimes they might even have one themselves.”

Students then develop 12-week intervention plans and lead the class through sample exercises. “We’ve heard ideas for drum circles, cooking classes, virtual reality paradigms —even goat yoga,” Harrison says. “Everything is fair game, so long as it hasn’t been studied before and can be justified scientifically.”

“My hope is not only that they learn to think about the body holistically in whatever field they pursue, but also that they do so for their own well-being.”

Elinor Harrison

For the final project, students craft original research proposals relating to perception and movement. “Many students, especially our pre-meds, have spent years working in labs, getting great research experience,” Harrison says. “But they’ve rarely been asked, ‘What do you really care about?’ ‘What burning questions do you have?’

“They come up with so many great ideas,” Harrison says. She ticks off examples: Group

a capella singing to reduce depression in college students, using driving simulators to improve lower extremity function in people with cerebral palsy, self-portraiture to improve body schema and increase activity in the amygdala.

“My hope is not only that they learn to think about the body holistically in whatever field they pursue, but also that they do so for their own well-being,” Harrison says. “The body is important! Everyone can benefit from thinking more about how they move and becoming more attuned to habitual movement patterns.”