Pressure. Contraction. Pushing. Rupture. For many, these words point to the experience of labor and childbirth. For Michelle Oyen, something else also comes to mind.

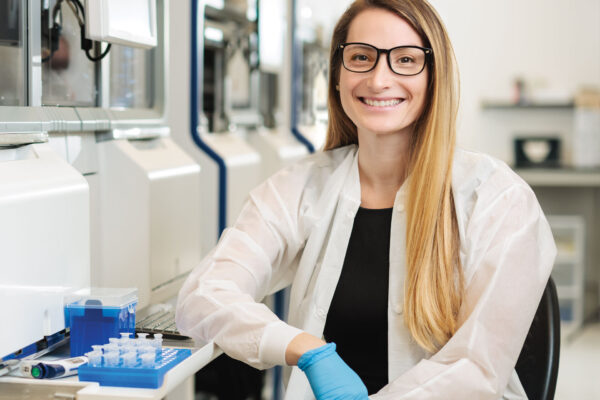

“These are all very clearly engineering words that have to do with physical forces,” says Oyen, associate professor of biomedical engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering. “We’ve been treating women’s health as solely a biology problem, but it’s also the realm of engineering and physics.”

As director of WashU’s Center for Women’s Health Engineering, Oyen seeks to bring medical practitioners and engineers together to improve women’s health care. Such collaborations have long proved successful in fields like orthopedics, but technological advances in women’s health have lagged — contributing to some startling statistics. One in 10 babies in the U.S. is born prematurely, for example. And maternal mortality is on the rise, especially among women of color.

“There’s a false idea in people’s minds that there’s no more to know about pregnancy. Of course, any woman who has experienced a miscarriage or stillbirth, or has ended up being induced early because of preeclampsia, will disagree,” Oyen says. “We don’t talk very often about how poorly we understand all this.”

“I’m not personally going to solve all maternal health problems. I’m part of a generation pushing the next generation forward toward solutions.”

Michelle Oyen, director of WashU’s Center for Women’s Health Engineering

Oyen points to a few root causes of the problem. For good reasons, medical experiments aren’t typically performed during pregnancy. Animal models don’t provide much helpful information, either. And, for decades, biomedical research was designed, performed and funded exclusively by men. This historical lack of gender diversity has likely also hampered the study of diseases that disproportionately affect women, like autoimmune disorders, as well as various conditions that lead hundreds of thousands of women each year to undergo hysterectomies.

The Center for Women’s Health Engineering is already making strides in overcoming these challenges. In one ongoing project, Oyen studies the placenta with Anthony Odibo, the Virginia S. Lang Endowed Chair in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the School of Medicine, and Ulugbek Kamilov, associate professor of computer science and engineering at the McKelvey School. Using machine learning and advanced imaging techniques, the researchers create computational models of placenta function. Such models provide insights into issues with the placenta that can occur early in pregnancy and cause long-term cardiovascular problems for both pregnant women and newborns.

“Everyone is born with a placenta,” Oyen says. “I think in the grand scheme of women’s health, this is what hasn’t been appreciated. We’re talking about things that affect all humans.”

Students, particularly women training to be physicians and engineers, are taking note. Alongside research and entrepreneurship, Oyen cites education and training as an essential pillar of the center.

“It’s exciting to see enthusiastic young women wanting to use their engineering skills in this field,” Oyen says. “I’m not personally going to solve all maternal health problems. I’m part of a generation pushing the next generation forward toward solutions.”