The Red Scare of McCarthyism has been revived in a frightening new form: the book-banning “Ed Scare.” So reports PEN America, a nonprofit advocating free expression in literature. Like the two Red Scares that pitted American citizen against citizen, the Ed Scare is virulent and broadly invasive.

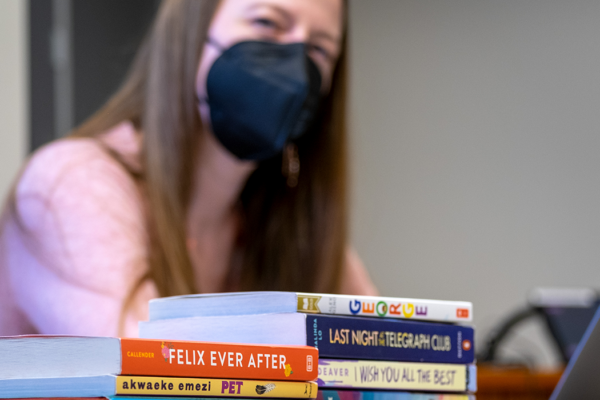

Although most Americans oppose book bans in libraries and schools, a highly organized, clamoring minority has stoked so much nationwide anger that in the 2022–23 academic year, PEN recorded 3,362 instances of books banned — an increase of 33 percent from the previous year. The most-frequently forbidden topics were race and racism, LBGTQ+ identities, physical abuse, health and well-being, and grief and death — even though many books had been carefully written for younger audiences. Missouri’s 333 book-ban cases ranked third in the nation. All numbers are expected to rise as the 2024 election approaches.

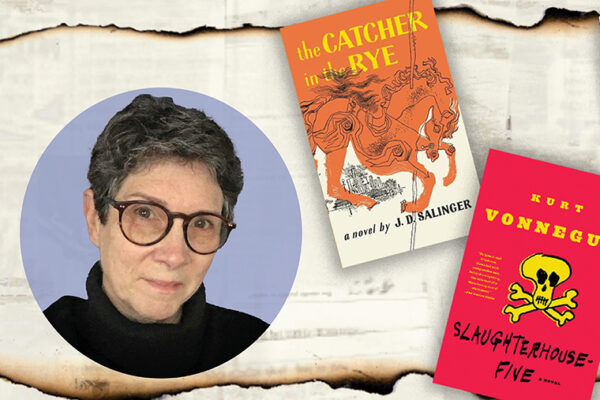

Enter Lisa Gilbert, a lecturer in education in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, brimming with ideas and empathy. She holds a doctorate in social studies curriculum and instruction and has expertise in the philosophy of education, among other proficiencies. Her primary mission is helping future teachers understand what children and teachers need, especially in today’s combative social climate.

Education is crucial to the rights and liberties of American democracy. It provides knowledge and, ideally, develops the mutual understanding necessary for citizens to work together to help their diverse society adapt to ever-changing times.

An essential part of education is social studies. Gilbert explains: “It answers foundational questions: Who am I? Who are you? How did each of us get to our present? How do we live together in this community, this society we share?”

Education is crucial to the rights and liberties of American democracy. It provides knowledge and, ideally, develops the mutual understanding necessary for citizens to work together to help their diverse society adapt to ever-changing times.

To accomplish all that, children must be allowed to weigh questions from multiple perspectives, to see themselves in the curriculum, to have productive conversations with classmates who have different opinions, to reach their individual informed conclusions while respecting other viewpoints and to at least think about how to act on their beliefs. That’s what democracy is — and what the book-ban culture is not.

Too often, children learn in classrooms where memorization reigns, where there are either right or wrong answers (and even right and wrong questions), and where tests tend to feature multiple-choice questions. As a result, children become preoccupied with getting every question right. Preparing for multiple-choice standardized tests also detracts substantially from teaching time. “What policymakers in many states also fail to understand,” Gilbert says, “is how much standardized testing has shifted our students toward the need to feel certain about things — whereas our lives in this world are filled with ambiguity.” (The state of Missouri has enshrined certainty by changing the name social studies to social sciences.)

Actually, Gilbert says, children can understand and be comfortable with the gray areas pervading reality. As they express their different points of view on a variety of topics, supported by worthy information they’ve been taught to evaluate, they develop intellectual and emotional depth. “Ultimately, students will feel empowered to go out and be whoever they are becoming. We are never finished!”

(A real-life example of empowerment, which occurred after-hours: Gilbert’s nephew in early elementary school recently dictated, following discussion, a letter to the designers of a planned wheelchair-accessible playground near his home that, somewhat inexplicably, would omit a sandbox. In it he said he loved sandboxes, and with Gilbert’s help, he provided printed examples of ones that children in wheelchairs also could use. He is eagerly awaiting a reply.)

“Topics that frighten some parents prevent them from wanting their children to read about them, whereas research is suggesting that children are actually capable of learning about difficult matters — and benefiting — in ways suitable to their ages.”

Lisa Gilbert

Gilbert and classroom teachers empathize with parents’ concern for their children and the fears the Ed Scare has invoked. But as she points out, religious and political beliefs and family values prevail in a home, and parents are the strongest influence on children. Worried families should open discussions with their children and with their teachers to express their views and should in turn listen carefully, thoughtfully and respectfully.

Parents might also be helped by understanding that the catastrophizing in book-ban messaging can also stir up adults’ own discomfort with painful aspects of our past. To protect themselves, adults sometimes project their emotional distress onto their children and assume they can’t handle a certain subject in school. “Topics that frighten some parents prevent them from wanting their children to read about them, whereas research is suggesting that children are actually capable of learning about difficult matters — and benefiting — in ways suitable to their ages,” Gilbert says. “In 20 years of teaching, whether in schools or museums, I’ve never met a child who was not able to engage with nuanced and occasionally painful topics when those topics were framed for them in a developmentally appropriate and sensitive way.”

But what of the teachers?

Rattled and alarmed by Ed Scare media attacks and a range of confrontations including irate, often discourteous parents, many teachers feel threatened and discouraged. In Missouri, teacher retention and teacher recruitment are increasingly worrisome problems. “The cultural respect of teaching has in many ways been lost,” Gilbert says. “Teachers no longer feel valued and honored, and they may also suffer moral injury when they are unable to teach in a way consistent with their values.” Such severe stressors cause teachers to burn out and leave the profession.

To empower future educators to work successfully with students, Gilbert integrates teaching difficult and controversial topics into many of her classes on elementary, middle and high school teaching. It’s an approach to teacher education consistent with WashU’s strategic plan and the education department’s theme of advancing equity. In her methods courses, she works with Sarah Nash, community engagement manager of the Gephardt Institute for Civic and Community Engagement, who gives workshops featuring role-play activities. The scenarios help the teachers-in-training practice thoughtful engagement in discussions involving various perceived conflicts: a community member is upset that you’re teaching “critical race theory,” for example, or a parent calls demanding that “coffee with the cops” be canceled. Says Gilbert: “As teachers, they must communicate helpfully with parents, manage controversy and continually try to build the relationship between the parent, the teacher and the school. We all need to be in the service of the child at the center of it all!”

“The best teachers know that being child-centered means taking young people seriously, even from the youngest ages.”

Lisa Gilbert

At the same time, teachers need to know each individual student — to recognize how much each student understands as well as the emotional needs and motivators of each one — and then teach in a responsive way so that what happens in class can be truly meaningful. “The best teachers know that being child-centered means taking young people seriously, even from the youngest ages,” Gilbert says.

To attract and keep the kind of teachers Gilbert prepares, parents and the community must work productively together. Parents can build thoughtful relationships with teachers and other parents — especially those who might not feel included already. They can also write letters to local newspapers, host mixed gatherings and attend PTA, school board and community meetings, ready to engage in respectful conversation. “We must work together as a society to make things less hard,” Gilbert says. “Right now, some of us are losing that faith in each other, and we are losing it on both sides of the aisle. We need to have faith in each other’s ability to listen and learn and grow.” Then she says with a smile, “Social studies is everywhere!”