In 1997, to mark the 10th anniversary of James Baldwin’s death, Dwight A. McBride proposed a four-person panel for the Modern Language Association. He was stunned by the reaction.

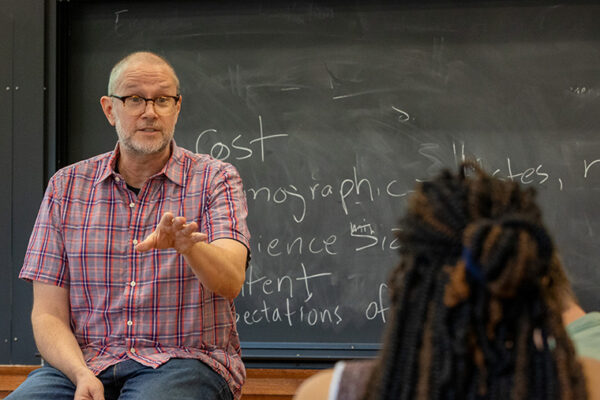

“There must have been 50 respondents,” remembers McBride, now the Gerald Early Distinguished Professor in the Department of African and African-American Studies in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

Baldwin, for all his renown, hadn’t yet generated the scholarly engagement accorded to peers like Ralph Ellison or Richard Wright. Nevertheless, “we got papers from people in political science, history, literary studies … Clearly interest was bubbling up.”

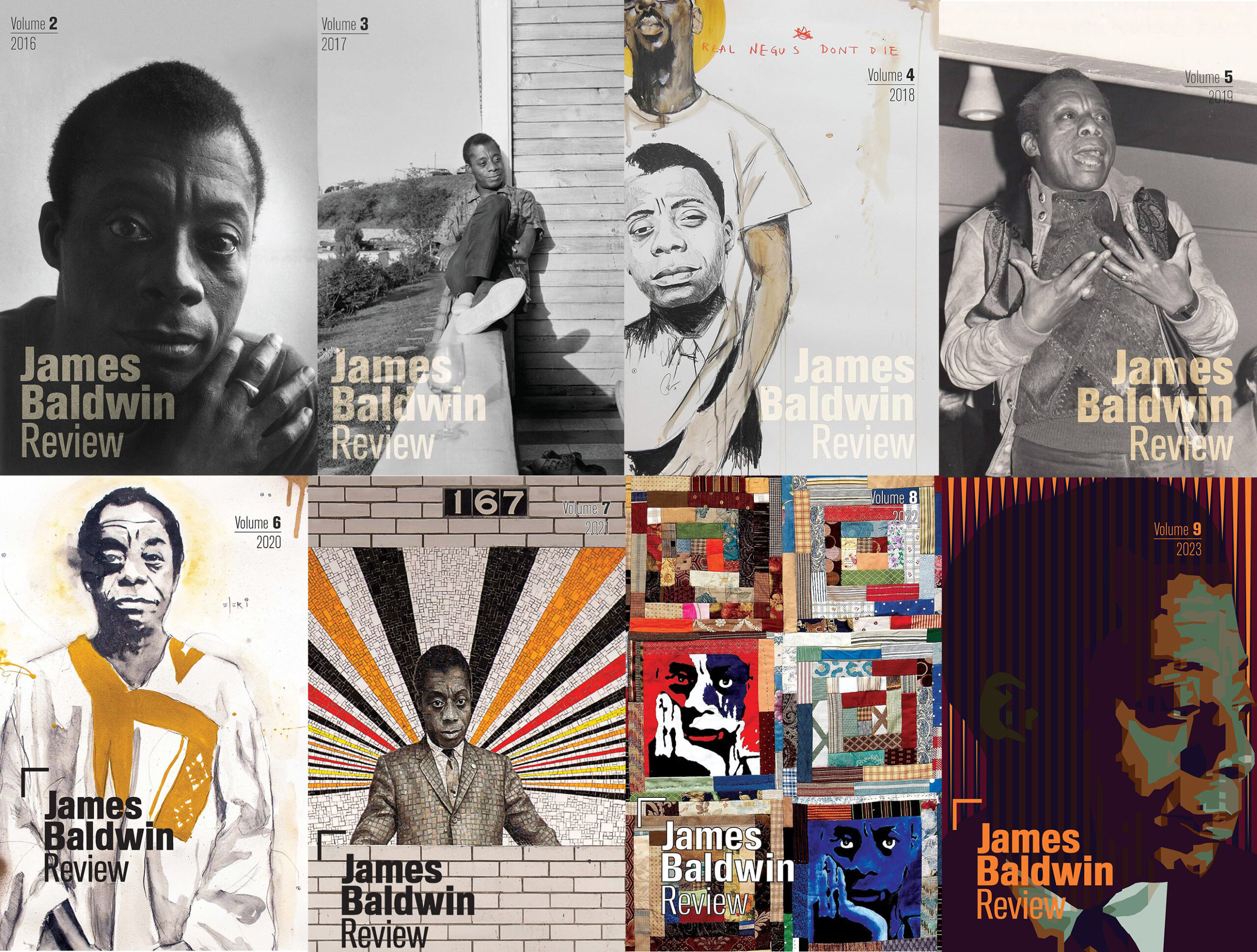

McBride recruited many of those authors for his influential 1999 collection “James Baldwin Now.” A decade later, he began working with Justin A. Joyce and Douglas Field to co-found a journal, James Baldwin Review. Now co-published by WashU and Manchester University Press, the review has become the preeminent academic journal dedicated to Baldwin.

In this Q&A, McBride and Joyce — the review’s managing editor, who like McBride joined the Department of African and African-American Studies this fall — discuss Baldwin, academia and why his writing remains so compelling.

What first drew you to Baldwin?

McBride: In graduate school, a friend gave me a copy of Baldwin’s essay “The Preservation of Innocence,” which to that point had gotten very little attention. Baldwin talks about his struggles with the church and with his homosexuality.

I am a son of the South, an African American man who hails from rural South Carolina. But it was one of those moments where you feel — where I felt — less alone in the world. It had a profound impact, and really started me on my Baldwin journey.

Joyce: I started working with Dwight, as a student and research assistant, at the University of Illinois Chicago. It was around the time “James Baldwin Now” was released, so I was aware of Baldwin’s growing profile.

But later, during graduate school, I was looking at archetypes of American masculinity and grappling with a question: Why do we see all this simmering anger? Rediscovering Baldwin, who just quite simply told the truth about it, was revelatory.

I think that’s why so many people who aren’t professional critics keep coming back to Baldwin. He had the ability to tell the truth.

Baldwin was famous during his lifetime, but you contend his work was understudied. Why?

McBride: For a long time, the scholarly record did not match Baldwin’s extraordinary productivity. One reason for that, I think, is garden-variety homophobia. Literary criticism had not sufficiently evolved to deal with the complexity that is Baldwin.

He also eschewed labels. It was only much later, with the advent of cultural studies and post-structuralist theory, that we started to think about concepts like intersectionality, and to de-essentialize our reading of texts by Black writers.

We needed a criticism that could appreciate Baldwin in all the ways that his writing demands.

Justin, you worked with Dwight on “A Melvin Dixon Critical Reader” (2006) and later contributed to “A Historical Guide to James Baldwin” (2009). How did James Baldwin Review come about?

Joyce: In 2009 or 2010, Douglas Field, from Manchester University in the U.K., reached out to Dwight and me. The idea was, ‘Hey, there is no Baldwin studies journal. Why don’t we make one?’

It took a while to figure out. Do we need a scholarly society? Will it be subscription? Open access? But Douglas was coming to Baldwin in the same way we were: Here’s a writer that we need to be talking about, that people need exposure to, who is telling the truth about the world.

In the end, you did make the review open access. Why?

McBride: That was very important, but there was some push and pull.

Joyce: Part of the struggle was institutional. We have readers in 125 countries, which is incredible, and which we couldn’t have done with print alone. But if you want junior scholars to write for your journal, and for your journal to be the flagship in its field, then your journal needs to count for promotion and tenure.

And the way that happens — especially in 2010, when we’re trying to start this; and in 2015, when the first volume comes out; and still today, in 2023 — it needs to be in print. It needs to somehow look and feel different from a website or a blog. And so how do you do that? You partner with a university press.

We do have a small print run every year. It’s an offering, if you will, to the Luddites of the world. And I will say — Dwight is smiling — I was the one who insisted it had to be printed.

McBride: We have libraries who want the print runs, too.

In many ways, being open access was an experiment, but for a relatively young journal, we’re punching above our weight. The community of Baldwin scholars has really come together.

There’s more communication and more collaboration.