Publishing is both a centuries-old intellectual tradition and a sprawling contemporary practice. Yet at its core, publishing seeks to answer one overarching question: How do ideas make their way into the world?

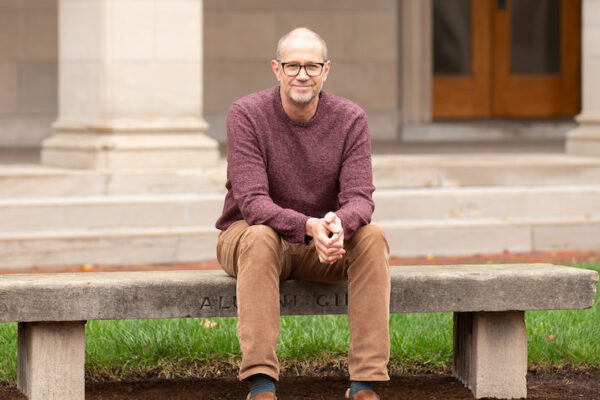

So argues Martin Riker, director of the new publishing concentration in the Department of English in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

In this Q&A, Riker — an acclaimed novelist and co-founder, with associate professor Danielle Dutton, of the award-winning publishing project Dorothy — discusses the new concentration, the state of the publishing industry and the importance of theorizing the means of distribution.

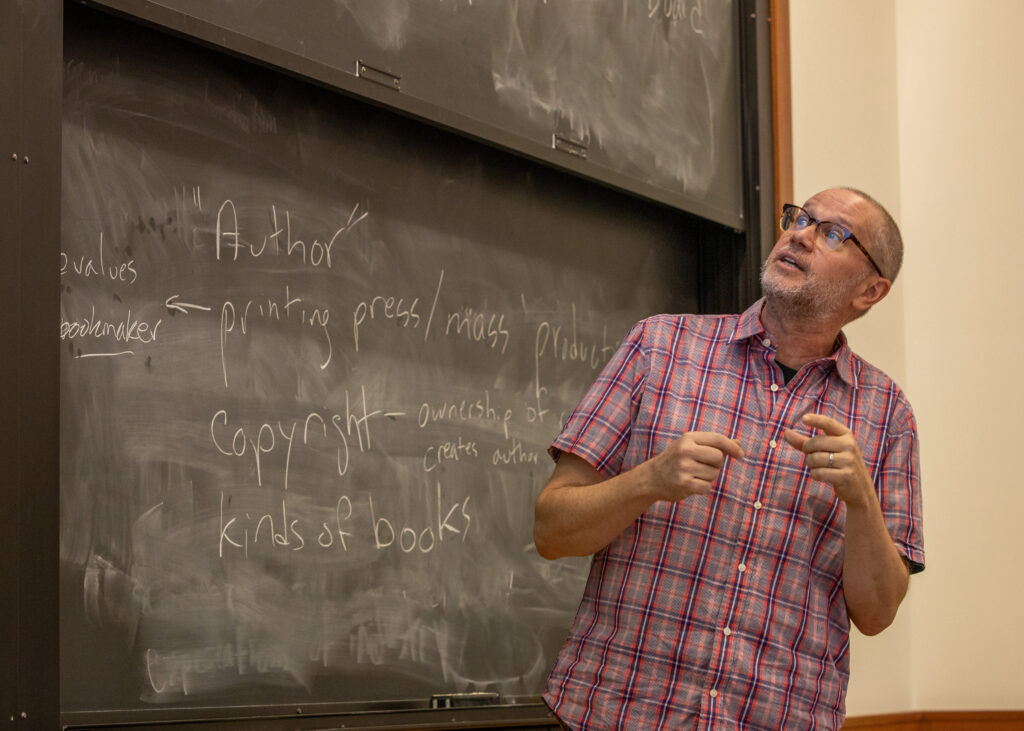

The publishing concentration is built on three required courses: ‘Copy Editing,’ led by Jennifer Arch, teaching professor of English, as well as your two classes, ‘Publishing History & Contexts’ and ‘The Art of Publishing.’ Tell us about those.

“Publishing History & Contexts” is an academic class that looks at the history of the book, and specifically the history of Anglophone publishing. We also talk about issues that publishing faces, and have frequent class visits from professionals in the field. But I’d say our true subject is the distribution of ideas.

“The Art of Publishing” is more of a practicum about how books are made. We go through the complete process with two different books, one from an independent press, the other from a big commercial house. Students read the books, write reader’s reports — a sort of tool used by editors — and create ads and marketing materials. We’re focused on rhetorical writing, which is a bit different from writing papers for a class. You have to think about who your audience is and how to connect to them.

Sounds like good practical experience.

The practical element is essential, but there’s also an important conceptual element. Academia is good at dealing with ideas, but historically we’ve done a fairly bad job of theorizing about how those ideas get out into the world.

But the culture is starting to recognize that systems of distribution can be sites of legitimate critical discourse. Over the next 10 or 15 years, I think publishing — the processes by which cultural production becomes public — will become a focus of humanities education across the country.

Has social media, with its foregrounded follower counts and affectations of real-time engagement, changed the way we think about distribution?

It certainly has, but it’s not alone. The rise of Amazon, the changing formats in which we read, the consolidation of corporate publishing — we are in the midst of a paradigm shift, a real Gutenberg moment.

And there’s the precarity of the culture itself. For a long time, we took a certain stability for granted. Today, the instabilities — the rise of fake news, the obstacles to finding reliable information, the way information is treated online — have become more visible.

We need to pay attention. In a lot of ways, this is how we make our culture. Culture is not only about generating the best ideas. As a writer, as a critic and as a publisher, I can assure you, it’s not always the best ideas that get out into the world.

So we neglect logistics at our own peril?

I think that’s true across almost any cultural discourse.

In my classes, we bring in a lot of professionals to share their expertise. And that’s valuable for the students, but it also humanizes the industry. It’s easy to see publishing as this monumental set of institutions, rather than as individual people making individual decisions, based on their own lives or on presumptions about how things are supposed to be done.

When students get to sit down and talk with them, they realize that nothing is inevitable. Things happen because somebody made them happen. For whatever reason, somebody made a choice. And that awareness is very important to becoming a responsible member of the community.