Populism has always come in waves, sometimes rocking the status quo, sometimes reforming it. These days, though, it feels like a tsunami.

What are the implications of this trend for democracy? Curious, three members of the Washington University political science department in Arts & Sciences are collecting an unprecedented dataset of global social media. By analyzing such a massive and varied amount of data as it changes over time, they intend to find out what triggers populist rhetoric, how it spreads and when it does the most damage.

The project began when Jacob Montgomery, director of both the Transdisciplinary Institute in Applied Data Sciences and the American Social Survey, sponsored by the Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government and Public Policy, realized this trove of data was within reach. Because social media is concentrated into a handful of platforms, it is currently possible, for the first time in history, to study — simultaneously, in detail and over time — exactly how thousands of political parties and candidates communicate with the public and with one another. How they differ; what sort of rhetoric they use and in what circumstances; how people respond; how and when and why that response changes.

If he moved quickly, Montgomery could use CrowdTangle, a social media tracker that Facebook’s parent company, Meta, opened to give journalists and academics easy access to content posted on public pages. (Meta reportedly plans to shut down CrowdTangle, which was used by reporters during the 2020 elections to track the spread of disinformation on Facebook. But academics are likely to retain access to some version of the tool.) If Montgomery could amass the Facebook posts of political parties and candidates in 79 democratic countries, it would be the largest dataset of political campaign rhetoric ever assembled.

It may seem overwhelming to analyze the larger patterns in campaign rhetoric given this vast amount of data. But not to researchers who know how to handle it. WashU’s political science department ranks No. 12 in U.S. News & World Report’s latest comparison of the best graduate programs in the nation. Montgomery, associate professor, already studies social media and the use of statistics to measure political concepts like ideology and populism. His colleague Christopher Lucas, assistant professor, is an expert in machine learning, especially for the analysis of natural language. And their department chair, Margit Tavits, the Dr. William Taussig Professor in Arts & Sciences, specializes in comparative politics, political parties and the influence of language. Even the book she co-authored, Voicing Politics: How Language Shapes Public Opinion (Princeton University Press, 2022), connects because it looks at the way peculiarities of language shape political attitudes and beliefs.

The three political scientists teamed up. With a grant from the Weidenbaum Center, they hired a postdoc, Taishi Muraoka, PhD ’19, to set up a protocol for collecting the information. How could they figure out who was running for office all over the world, in scores of different languages, and then keep tabs on their communications? Muraoka worked it out.

Impressed by the proposal, the National Science Foundation awarded the team $571,000 to finish the project in three years. There is, after all, some urgency to the questions they are asking.

The first challenge was agreeing on a definition of “populist,” a term that can be as slippery as a slime eel. Still, they knew what they wanted: rhetoric that juxtaposes the people against “the elite,” that portrays the people as being lied to, betrayed and misrepresented by the corrupt and disconnected elite.

Given populism’s orientation to “the people,” you’d think its impulse would be, by definition, democratic. That, says Tavits, is what makes this rhetoric potentially dangerous: “You say, ‘We are restoring democracy,’ and in the process, you are getting rid of all its institutions.” You cast doubt about their legitimacy, then persuade people that the process is not working in their favor.

Along the way, populist rhetoric often vilifies minorities such as immigrants, people of color, the LGBTQ community. Which is also a bit of a paradox for a technique that aims its scorn at the few who wield mainstream power. A movement that defines itself as anti-elite and “of the people” is siding against minorities within its own populace? “You hate the elite because they are favoring minorities,” Tavits explains. “The minorities are therefore a threat to your standing in society. You feel that your economic status and social status will suffer because of these accommodations.”

Populist rhetoric does not always target minorities, however. And while it is often used by the political right, it is not itself an ideology; its techniques can be invoked just as easily by the left.

“What unites all this rhetoric is its implication that the elites are corrupt, the political process is corrupt, and the institutions of democracy are not operating correctly,” Montgomery explains. To demonstrate, he raises his voice slightly, mixing the classic populist notes of frustration and frenzied idealism: “‘If only we were listening to the pure will of the people …’”

“We are not necessarily starting with the stance that all populist rhetoric is bad. But we study only democracies … and in the aggregate, this sort of rhetoric can fundamentally erode the basic tenets of democracy.”

Jacob Montgomery

That pure will can be hard to discern, easy to manipulate and, in some cases, have basis in accurate critiques, he says.

“For any particular claim, there could be some truth behind it, some valid concern,” Montgomery continues. “We are not necessarily starting with the stance that all populist rhetoric is bad. But we study only democracies — we’re not studying, for instance, Russia — and in the aggregate, this sort of rhetoric can fundamentally erode the basic tenets of democracy.” A constitution, for example. The peaceful transfer of power. Acceptance of election outcomes. The need to obey the law.

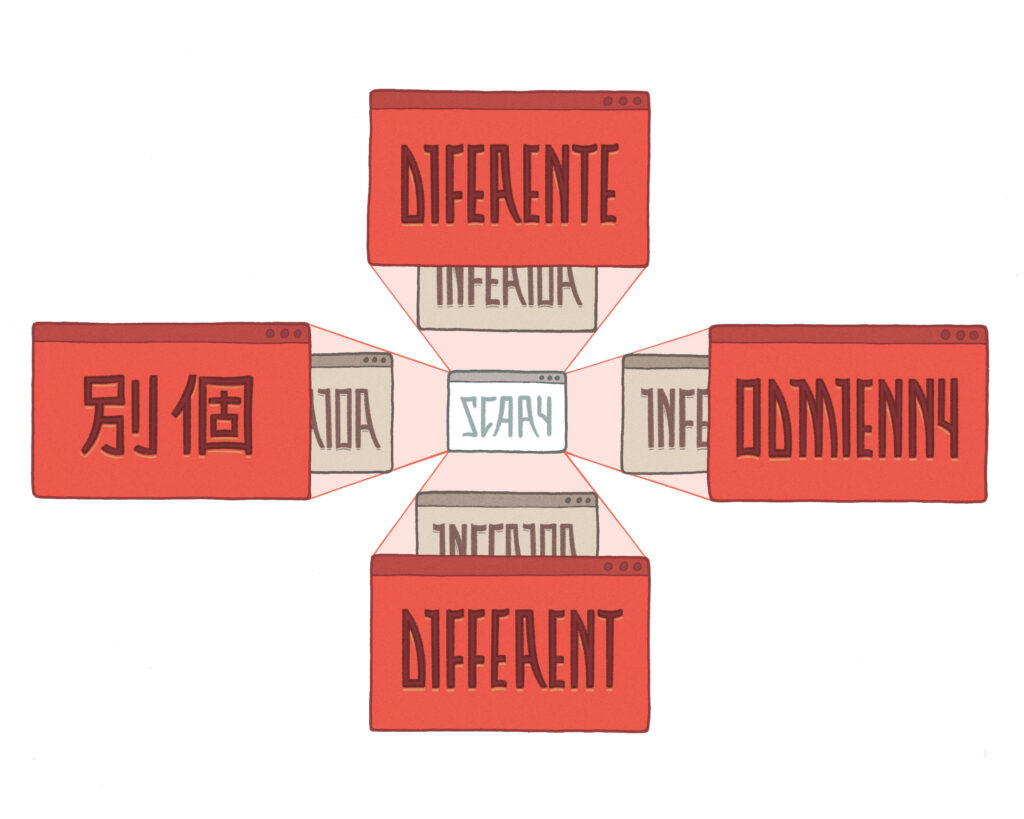

The team’s second challenge is the many languages they are trying to compare and analyze. In the past, political scientists have used snapshots of data, freezing one moment in time, or compared political parties’ manifestos. The exciting change with this project is its ability to gather and compare more dynamic, rapidly shifting data over time. But that means working across many different languages.

“The simplest way to analyze documents written in different languages is to translate them all into a single language spoken by the researcher and proceed as if the documents were in fact monolingual,” Lucas says. “But that’s unsatisfying and inelegant, and it can be unreliable.”

Translation is difficult: Languages are stuffed with quirks and layered with nuance, subtext, connotation, idiom. AI translation is improving fast for oft-spoken languages in which the algorithms can be trained on a huge assortment of documents. But what about, say, Tagalog, for which far less data is available for training?

“Machine learning and computation, though, are moving so fast,” Lucas continues. “An approach that was cutting edge a few years ago has likely been replaced by something faster and more accurate. With recent advances, we can automate the analysis of millions of social media posts written in dozens of languages about a range of topics.”

You can train your algorithm to recognize populist rhetoric, he says, feeding it examples in different languages, and then let the model label that sort of rhetoric in all languages.

Tavits’ expertise rests not with the programming of machine language but with the influence of human language. She grew up in Estonia, and because only 1 million of its 1.39 million residents spoke Estonian as their first language, she learned Russian and English, then added German, French and Spanish. “And we lived close to the Latvian border,” she adds with a grin, “so you at least need to know the Latvian word for ice cream!”

Through her childhood, Estonia was occupied by the Soviets. She was in her teens when the USSR collapsed and democracy was restored. She listened, hard, to political news — about her own country but also about the rest of the world.

All that exposure to different political systems and different languages made an impression. A hodgepodge of political parties was emerging in Estonia, and the political landscape was volatile. “All those dynamics fascinated me,” Tavits recalls. “I started trying to understand how people formed successful political parties — and how they communicated with the people they were trying to reach.”

She was becoming aware of linguistic nuance and of the subtleties of language’s influence on behavior. In English, she noticed, euphemism was more common — maybe as a strategic attempt to draw the listener’s attention away from certain things? In other countries, politicians had a choice about which language to use, and that could also be an election tactic. Tavits began reading articles in psychology and linguistics, combing through the research on various language effects and trying to figure out how those findings would apply to political science.

Now years later, political language is finally emerging as a field of study. The people who construct those omnipresent polls, for example, rarely pay real attention to language. “They think about it as a background variable,” Tavits says, “but they never stop to think, ‘If I ask the same question in Spanish instead of English, is that going to introduce systemic error into the responses?’ The answer is always yes. But what the bias is depends on what you are asking.”

She has been exploring that sort of bias for years, weaving it into her research in comparative politics. Understand how language affects the thought process, and you will have a better grasp of the way people form political attitudes, how language’s quirks and semantic differences nudge our attention, how tone affects our responses, and why outcomes vary across nations and regions.

While populism is mostly a rhetorical tool, Tavits knows from her research that words matter. And she stresses that it is important to understand the consequences — intended or unintended — of politicians using this tool.

Consistently, “populism has been tied to economic insecurity,” she notes, “and to increased immigration, which can be related to perceptions of increased crime or terrorism.” The comparison is not a direct one, but economic downturn in 1930s Europe raised similar tensions, allowing National Socialism — which had vivid streaks of populism — to spread. Well before World War II broke out, the Nazi party had unmoored Germany’s democracy.

Today, you also must look at the immediacy of communication, she adds. Social media and 24/7 news reach across geographic boundaries and operate continually to amplify anxieties of all kinds. “People are feeding off one another’s fears, and it’s easy for politicians to tap into that.”

Her team pays close attention to emotion, which is increasing apace with the populist rhetoric — “particularly negative emotions such as anger,” Tavits says. “Part of what such rhetoric does, maybe intentionally, is rouse those emotions in people, because those are emotions that can lead to action.” Already, the team has drafted a paper analyzing the red hearts and raging orange emojis used to respond to various election results. “Electoral losers are more likely to express anger, which could be for two reasons: One, this populist rhetoric is increasingly present, and two, polarization has people moving so far from each other in their views that the other side is completely unacceptable to them.”

“In the U.S., it’s impossible to separate the effects of populist rhetoric from those of polarization. That’s why we need this comparative, global approach, so we can study contexts where there are multiple parties and polarization is more easily separable from populism.”

Margit Tavits

In the U.S., racism plays a strong role in both populism and polarization, as does the anti-immigrant sentiment and the other forms of bias (gender identity, religion, ethnicity, sexual expression) that are also prevalent in Europe. The common thread is one of perceived threat — which triggers fear, resentment and anger. As the project refines its analysis, the role played by different kinds of bias will need to be sorted.

How necessary is a pre-existing antipathy, anxiety, resentment or seething anger, if someone wants to galvanize populist support and trigger action? Can a skillful politician whip up a calm, contented electorate?

“It’s hard to say to what extent this is strategy,” Tavits notes, “and to what extent they just want to use that type of rhetoric, and anger is the byproduct.” Either way, “using language we normally considered outrageous is a populist tactic, because it’s anti-elitist.” When someone in the political elite starts using language in a way that defies the old definition of civility and shatters its taboos, such language is seen as a strength, not a weakness. Then “the herd mentality sets in,” she says. The norm-breaking behaviors have been normalized.

“In the U.S., it’s impossible to separate the effects of populist rhetoric from those of polarization,” she adds. “That’s why we need this comparative, global approach, so we can study contexts where there are multiple parties and polarization is more easily separable from populism. In Europe, the parties using populist rhetoric co-exist with mainstream leftist and rightist parties that may or may not be ideologically polarized. France, Germany and Sweden, for example, are not particularly polarized ideologically, but they have strong populist movements.”

To be clear, the team hasn’t determined yet whether populism undermines democracy — it’s something they want to find out. But if it does, the stakes could be high. “In Europe, often you have multiple parties and coalition governments,” Tavits explains, “so even if the biggest party became populist and could potentially be a threat to democracy, it still needs partners. It has to mellow, because if nobody wants to play with you, you become a pariah, and voters soon figure out that you are incapable of actually getting anything done. So more radical parties, if they do get into government, tend to either implode or change drastically.” It’s hard to be anti-elitist once you become the elite.

“A two-party government like the U.S. generally works very well,” she continues. “But if there’s a nondemocratic actor, then other institutional mechanisms become more important as checks and balances.” Multiple parties might set up a better defense mechanism, Tavits says. “But even the two parties in the U.S. are aggregates of multiple factions, and the scenario where one of those factions takes over the entire party — in theory — isn’t very likely.” Nonetheless, it can happen. And when it does, “it’s very dangerous.”

As soon as the project’s challenges are sorted and its methods validated, the team “can start using this wealth of data to answer substantive questions,” Montgomery says. “First, descriptively: Which parties use populist rhetoric, which politicians, in response to what events, and how does it spread? Who copies whom? That will help us get a better handle later, when we start explaining the spread, usage and effects.”

To understand the effects of populist rhetoric on voters, they plan to do a separate data collection, using cross-national surveys to ask voters a series of questions. First, they will measure the voters’ emotional arousal, then the effect of that emotion on their willingness to take action.

This project will also help assess social media’s influence on politics. “Political rhetoric is more visible on social media,” Montgomery says, “but it’s not clear that social media has caused the increase. Having this data will make its effect clearer, because there are still countries where the internet is just now coming on.”

Meanwhile, this dataset will open myriad other research opportunities, because it holds clues to language, culture, beliefs, bias, social connections, group behavior, thought, emotion and political power — how it is organized, how it is amassed, how it fades, when it flares again.