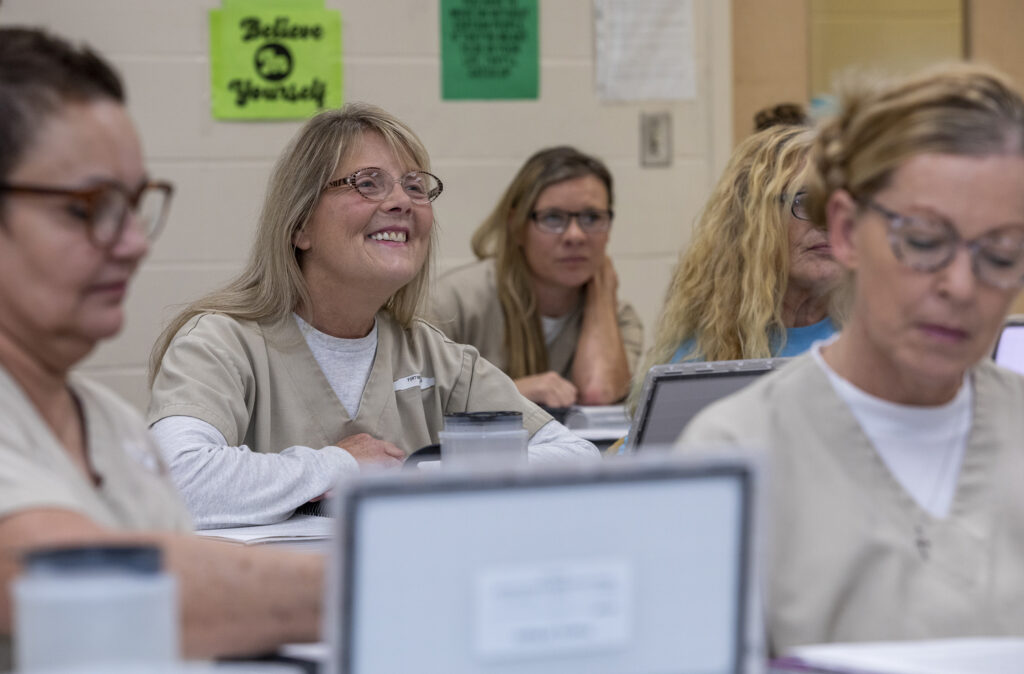

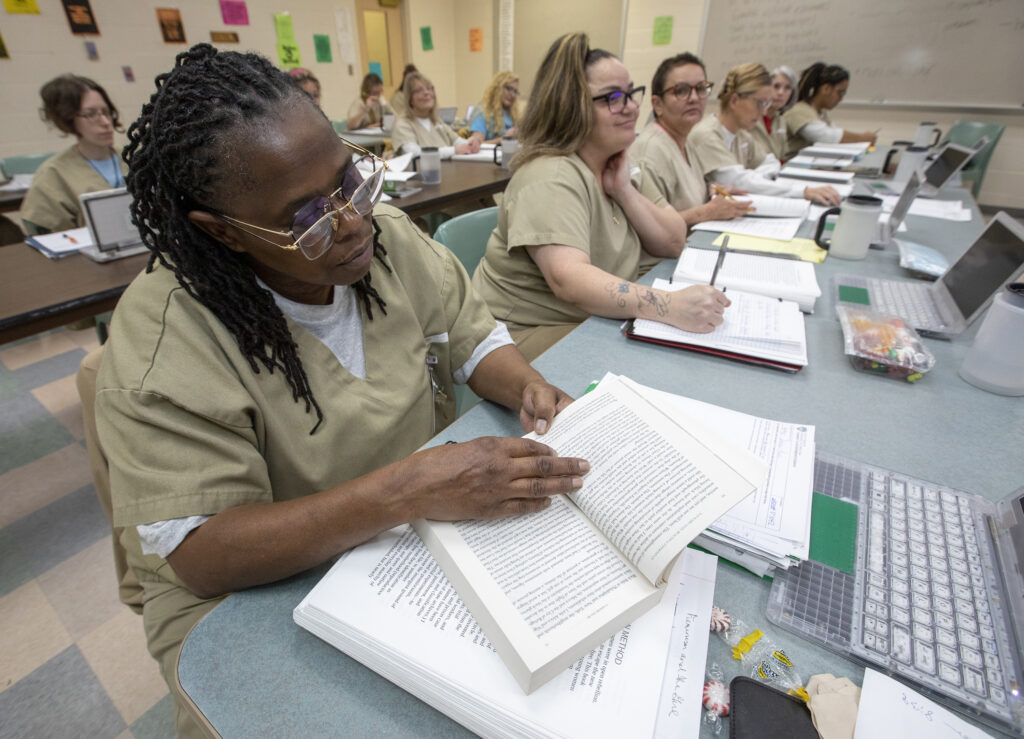

It’s a brisk afternoon in northeastern Missouri, and students in the Washington University in St. Louis Prison Education Project (PEP) are talking about Greenpeace.

The class is analyzing a passage by Paul Watson, a controversial founding member of the environmental group, whose hard-nosed tactics ultimately led to his expulsion.

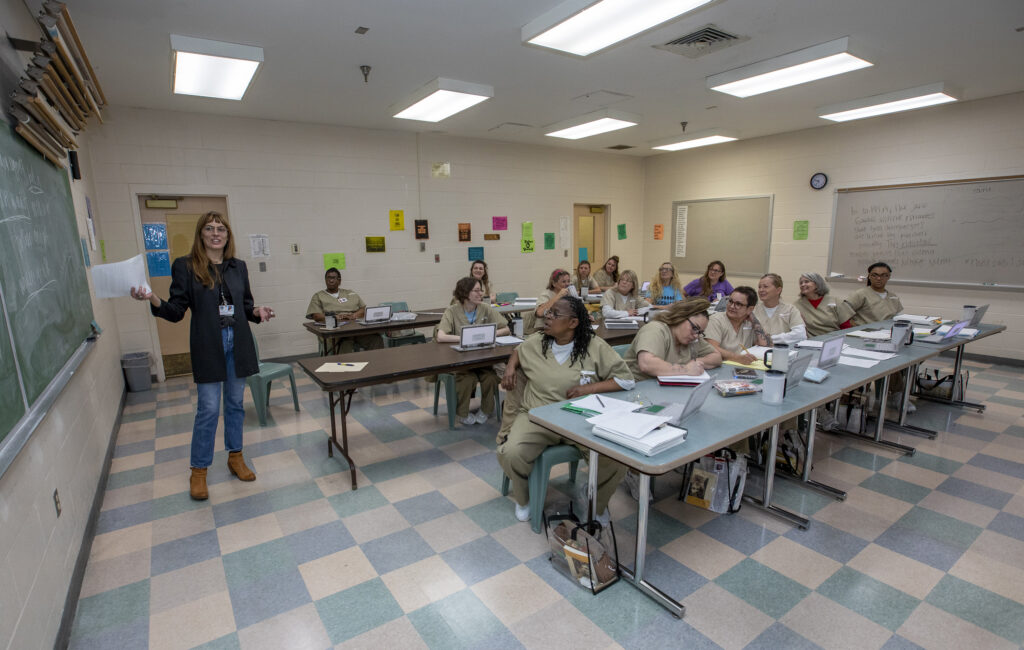

“These are provocative ideas,” said Meredith Kelling, a PEP postdoctoral research fellow who is leading the discussion. “But what’s the thesis here? That a true activist needs to go farther? What evidence do we, as readers, need to support that?”

“We want to know more about the organization,” student Yvette Mahan said. “We want to know the context.”

“They’re putting the whalers at risk,” rejoined Hettye Johnson-Ross. Patty Prewitt concurred. “Whalers are just doing their jobs.”

“There needs to be an argument there, not just an opinion,” observed Sandra Dallas. However sincerely held, Watson’s confrontational philosophy is “just not translating to paper,” added Amy Walker.

Expanding courses

Since launching in 2014, the Prison Education Project has offered dozens of courses to incarcerated students at the Missouri Eastern Correctional Center, a men’s prison located in Pacific, Mo. Last fall, the project expanded to a second facility, the Women’s Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center in Vandalia, Mo.

“Even as the field of higher education in prison is growing, educational opportunities for incarcerated women have tended to lag behind those available to incarcerated men,” said PEP director Kevin Windhauser. “We’re excited to help incarcerated women in Missouri access the same WashU education that has made a difference in the lives of so many of our students.”

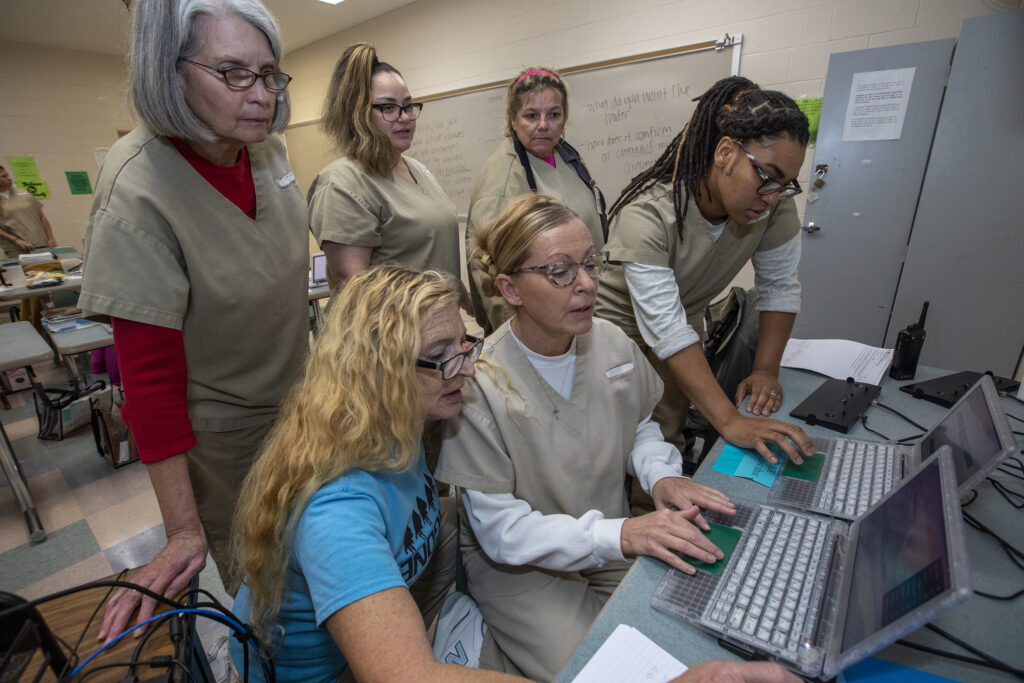

A $980,000 two-year grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation enabled the expansion. The grant also supported development of UnlockED, a new digital learning management system that PEP is testing with Vandalia students.

“It’s basically a custom version of Canvas,” the open-source platform widely used in higher education, Windhauser explained. Built at the Missouri Department of Corrections’ Potosi facility by a team of incarcerated programmers — including Jessica Hicklin, who would go on to co-found UnlockED Labs — the system allows PEP instructors to share course materials, deliver feedback and, when necessary, teach classes remotely.

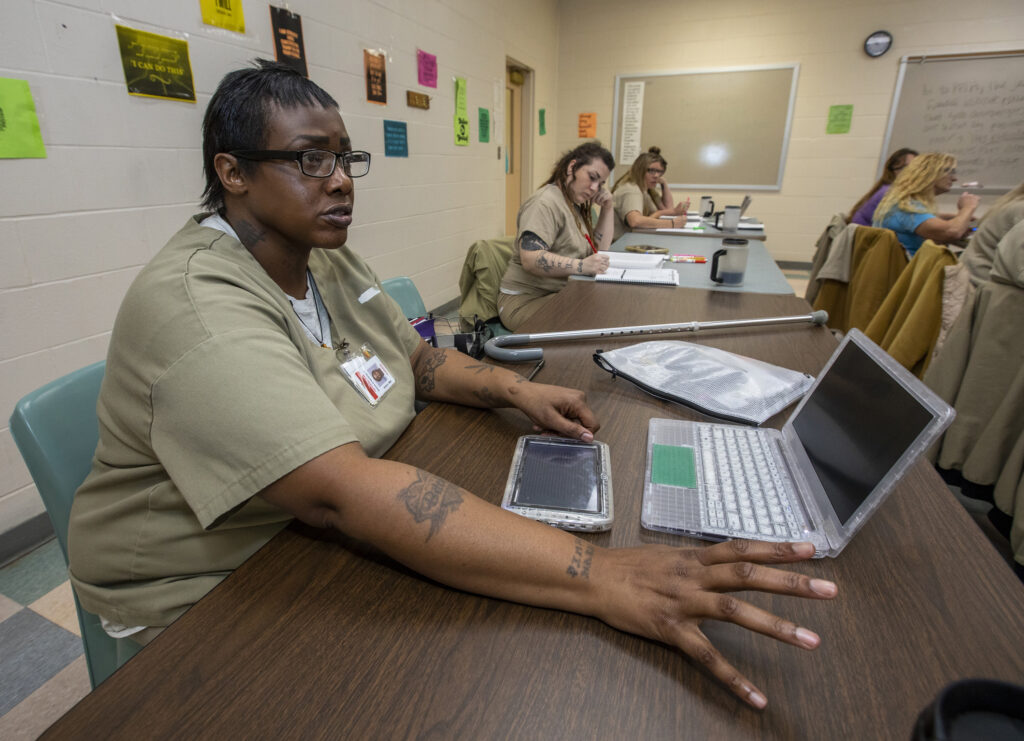

To run UnlockED, each student is issued a SecureBook, a proprietary laptop manufactured by California-based Justice Tech Solutions. Encased in clear plastic and lacking standard ports, SecureBooks come pre-loaded with a suite of basic software — including a web-browser that can only access sites “white-listed,” or pre-approved, by the Department of Corrections.

Windhauser and Hicklin, who was released in 2022 and currently serves as UnlockED’s chief technical officer, plan to introduce the system to the Missouri Eastern Correctional Center next fall. Eventually, they hope to make it available to other prison education programs. Windhauser pointed out that with job and housing searches now conducted primarily online, digital literacy has become a basic requirement for navigating contemporary life. Indeed, he added, scammers often target the recently released, seeing them as uniquely vulnerable.

“UnlockED is a secure system,” Windhauser said. “It’s also a system that promotes long-term security.”

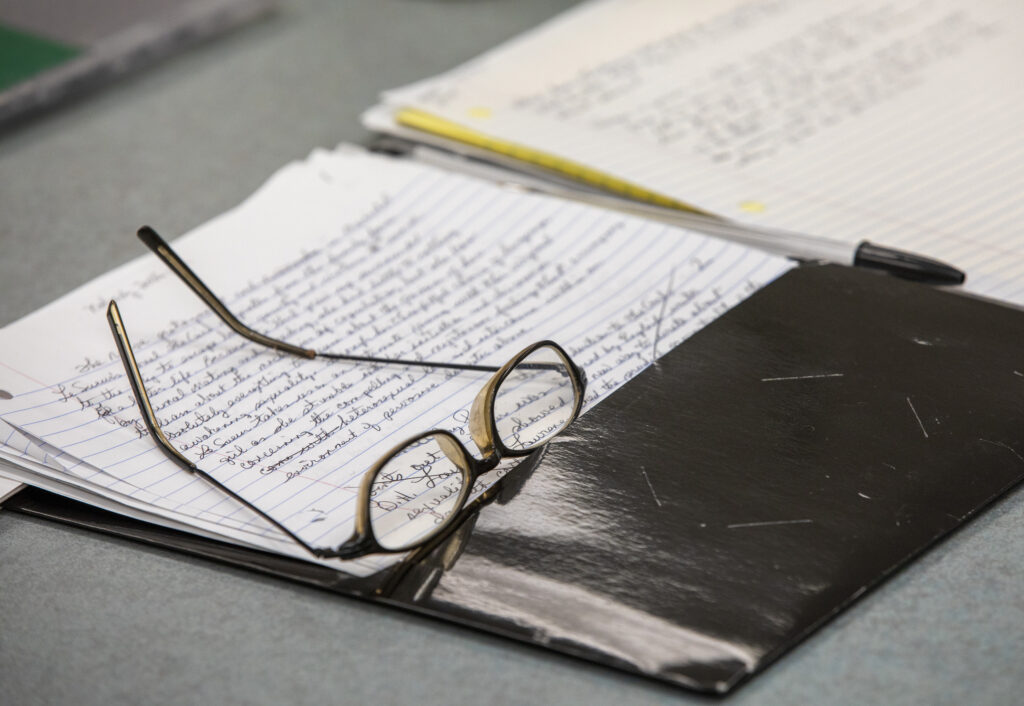

Individual voices

Vandalia, located about 100 miles northwest from St. Louis, is a small city of approximately 3,500 surrounded by rolling farmland. The correctional center, which opened in 1998, is the primary intake point for incarcerated women entering the state system, though it also houses a significant resident population. Approaching the entrance, one glimpses a small playground for use during family visits.

Kelling, who makes the four-hour round-trip drive every week, earned her doctorate in 2021 from WashU’s Department of English in Arts & Sciences. Her scholarship focuses on how Black and working-class discourses, especially those of women, have been overlooked within the broader field of literary studies.

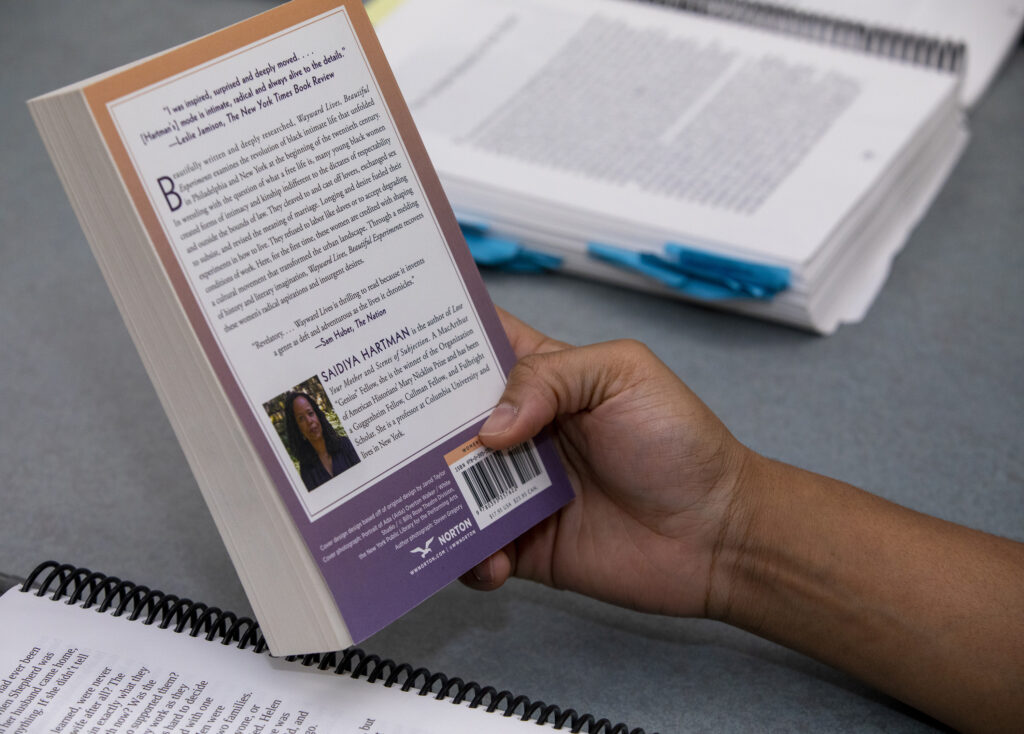

Following the Greenpeace discussion, Kelling turned students’ attention to “Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments” (2019), an exploration of Black life in early 20th-century New York and Philadelphia, by the influential Columbia University scholar Saidiya Hartman. Drawing on a range of archival materials, from journals and interviews to rent rolls, trial transcripts and parole reports, Hartman showed how young Black women, rejecting expectations of second-class citizenship, challenged Victorian norms about love, work, courtship and family.

Raising a hand, Dallas observed that for all of Hartman’s voluminous research, the author’s true gift is for reconstructing individual voices and perspectives. “She’s not talking about them,” Dallas said. “She’s talking through them.”

“They weren’t just vagabonds and prostitutes and rebels,” Walker added. “They were independent and strong.” The lives these women forged “did something to progress history.”

For the next 30 minutes, the conversations wheeled from the demographics of underground jazz clubs to the precarious camaraderie of impoverished neighborhoods to the work of housing advocate Helen C. Jenks, co-founder of Philadelphia’s Octavia Hill Association.

“Does this seem like a potentially liberated space?” asked Kelling, gesturing to a Jenks photo, taken in the late 1890s or early 1900s, of a ramshackle alleyway.

“Yes!” said Dallas.

“No!” said Prewitt.

“It’s just their life,” Mahan said. “It’s how they live, it’s how they get through the day.”

“You see the trash and the dilapidated houses,” Riana Sanders said. “What you don’t see is the unity.”

“So we have multiple truths existing at the same time?” asked Kelling.

“Like this place here!” said Brooke Wade-Vaughan. The room dissolved in a wave of laughter.

“When you remove all the barriers — circumstances, social status, judgment — you see people for who they really are,” concluded Theresa Fortner. “You see humanity.

“Each individual person has a beauty and a story to tell.”