Hummingbirds have the fastest metabolism of any animal. The tropical hummingbirds that live in the Andes Mountains in South America must expend considerable energy to maintain their high body temperatures in cold environments.

One tool that they use to survive cold nights is called torpor, a hibernation-like state that allows them to ramp down energy consumption to well below what they normally use during the day.

But it’s not just a matter of flipping a switch that turns metabolism on or off. Instead, hummingbirds use torpor in varying ways, depending on their physical condition and what is happening in their environment, according to new research from Washington University in St. Louis and Colombian biologists.

Colombia is home to 168 species of hummingbirds, more than any other country in the world. For this study, researchers caught 249 hummingbirds representing 29 different species living in the mid- to high-altitude mountains. The scientists collected measurements related to torpor in the wild (as opposed to studying the birds under laboratory conditions).

“Torpor is somewhere between a power nap and hibernation,” said Justin Baldwin, a PhD candidate in biology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University, first author of the new study published March 15 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“Earlier research had suggested that torpor was a way of completely shutting metabolism down to minimal levels,” Baldwin said. “Our findings join a growing body of evidence to suggest that when animals enter torpor, they have diverse options to calibrate aspects of torpor to their environment.”

For example, the researchers found that hummingbirds can enter into deep or shallow torpor; they can remain in torpor for just a few hours or the entire night; and they can begin coming back from torpor hours or just minutes before sunrise. When they exit torpor, some hummingbirds warm up gradually, while others return quickly to normal body temperatures.

Small birds were more likely to use torpor than large birds, but only at low ambient temperatures, where torpor lasted three hours or more.

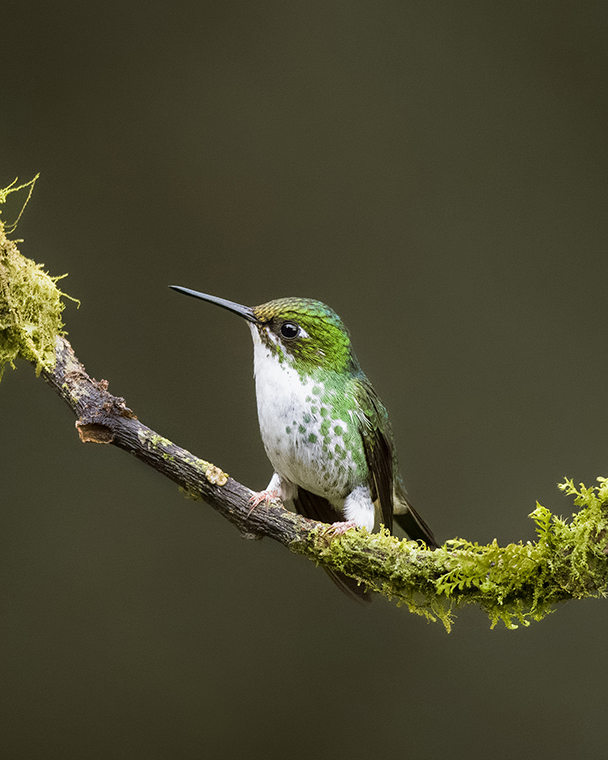

A greenish puffleg (Haplophaedia aureliae) (on left) and two male booted racket-tails (Ocreatus underwoodii) are seen at La Minga Ecolodge, Valle del Cauca, Colombia.(Photos: Juan Fernando Pinillos Madrid).

“Torpor can be the difference between surviving through cold night-time temperatures encountered at high elevations, or dying trying to regulate their body temperature using fuel from their internal reserves,” said Gustavo Londoño, co-author of the new study and a professor at the Universidad Icesi in Cali, Colombia.

“One of the new things we learned with this study is that hummingbirds start exiting torpor more or less one hour before sunrise,” Londoño said. “Being out of torpor and ready to fly with the first sunlight is key to ensuring that their first meal will be from flowers that are full of nectar. The flowers then get depleted through the morning.”

Hummingbirds need to be in good physical condition to use torpor, otherwise they might not have enough resources to exit from torpor or survive cold nights. When the scientists caught hummingbirds that were in poor condition, they noted that these unhealthy birds exited torpor right at — or even after — sunrise, apparently waiting for heat from the sun to provide the extra energy to help ease them back into their normal, zippy selves.

An undergraduate student in Londoño’s laboratory, Diana Carolina Revelo Hernández, conducted much of the field research with the hummingbirds and is co-first author of the new study.

“We were only able to discover these subtle effects because Carolina collected so much data from multiple field sites at different elevations along the mountains,” Baldwin said. “She singlehandedly produced the largest individual dataset on hummingbird torpor, both with respect to numbers of individual birds and number of different species of hummingbirds. It’s an incredible amount of work.”

A female booted racket-tail (Ocreatus underwoodii) (left); a green hermit (Phaethornis guy); and a male long-tailed sylph (Aglaiocercus kingii) (right), are all pictured at La Minga Ecolodge, Valle del Cauca, Colombia. (Photos: Juan Fernando Pinillos Madrid).

Because the scientists studied so many species at once, they were able to address how torpor may have contributed to hummingbird evolution and the colonization of the harsh environments of the high Andes.

“Species that more readily deployed torpor at our study sites also occurred at higher elevations across the entire Andean region,” Baldwin said. “This is exciting, because it suggests that a characteristic of bird physiology can tell us something about their distribution across the entire continent.

“Even though we don’t know which came first — an increase in readiness to use torpor or the ability to persist at high elevations — we think that hummingbirds’ readiness to use torpor is likely tied to their evolutionary conquest of mountain habitats.”

DCR Hernández, JW Baldwin, GA Londoño. Ecological drivers and consequences of torpor in Andean hummingbirds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. March 15, 2023. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2022.2099