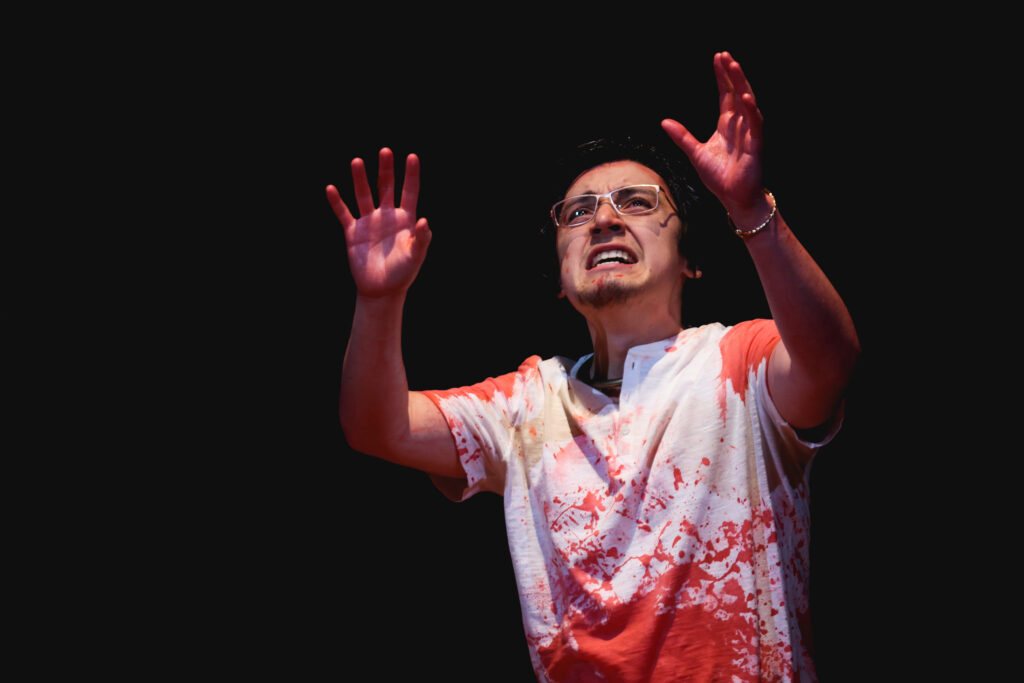

Can murder excuse murder?

On the eve of the Trojan War, Mycenaean king Agamemnon, in need of favorable sailing, sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia to the goddess Artemis. Upon his return, ten years later, Agamemnon is killed by Clytemnestra, his wife and Iphigenia’s vengeful mother — to the horror of their surviving children, Orestes and Electra.

In “The Oresteia,” her adaptation of the epic Greek trilogy, contemporary playwright Ellen McLaughlin explores cycles of violence, the ironies of vengeance and the often-tangled search for justice.

“When Clytemnestra murders her husband, certain debts are paid,” said Pannill Camp, associate professor of drama in the Performing Arts Department in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, who will direct the play Feb. 24 to March 5 in Edison Theatre.

“Agamemnon has racked up a series of transgressions,” Camp said. In addition to killing Iphigenia, “his wanton slaughter of Trojans, his enslaving of Cassandra, and his army’s excesses in sacking Troy are all distinct categories of crimes.

“And yet, in settling those debts, a new crime is committed,” Camp continued. “Electra and Orestes now feel obliged to repay Clytemnestra in kind.”

Amidst such interlocking tragedies, “is justice even possible?”

‘Humanizing the guilty’

Written by Aeschylus, a former Athenian soldier who fought at the battles of Marathon and Salamis, the original “Oresteia” comprises three plays: “Agamemnon,” “The Libation Bearers” and “The Eumenides.” In 458 B.C., just two years before the playwright’s death, the trilogy won first prize in the tragedy competition at the Dionysia, a major religious festival. (Second place may or may not have gone to Sophocles.)

McLaughlin’s adaptation, in its first two acts, largely follows the action of “Agamemnon,” which relates the king’s return from Troy and subsequent downfall; and “The Libation Bearers,” in which Orestes and Electra seek vengeance against their mother. Still, this streamlined version (the original trilogy would have lasted nine or 10 hours) finds time to emphasize fresh contradictions and complexities. For example, where Aeschylus described Iphigenia’s lot indirectly, as backstory relayed by the chorus, McLaughlin opens “The Oresteia” with a haunting vision of the doomed girl waking from a nightmare — and being comforted by her parents.

“In Greek mythological storytelling, the most interesting actions are ones where guilt is partial, or complicated, or extenuated,” Camp explained. “McLaughlin’s dramaturgy is saturated with a profound understanding and appreciation for these texts. Like Aeschylus, she is intent on humanizing the guilty.”

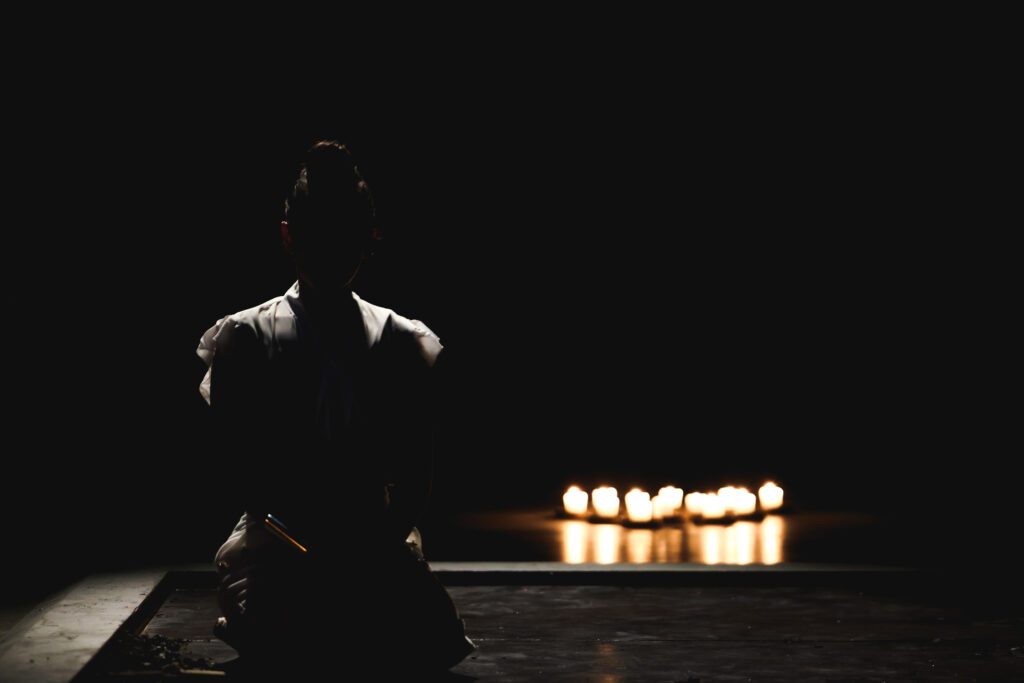

McLaughlin’s most radical re-imagining comes during the third act. In Aeschylus’ telling, Orestes is driven mad by the Eumenides, the Greek goddesses of vengeance (also known as the Furies). Meanwhile, Athena, goddess of wisdom and protectress of Athens, seeks to stem the bloodletting by calling for a jury trial, and casts the deciding vote herself.

“The ‘Oresteia’ is commonly understood as a kind of triumphal narrative, in which society moves away from retributive violence and towards democratic civic institutions,” Camp explained. But for McLaughlin, who began writing her adaptation in 2016, institutional shortcomings had grown all too apparent.

“Today there’s a sense of crisis about a lot of the institutions we’ve inherited,” Camp continued. Instead, McLaughlin looked for models of resolution in contemporary ideas about reparative justice, finding particular inspiration in the truth and reconciliation commission of post-apartheid South Africa.

Rather than falling to the gods, Camp concluded, “Orestes’ fate will be for humanity to decide.”

Cast and crew

The cast of 12 is led by Izzy Hobbs as Clytemnestra, Dylan McKenna as Agamemnon, and Alexander Hewlett as Orestes. Brenna Jones is Electra. Caitlin Souers is Iphigenia. Ella Sherlock is Cassandra. Eli Bradley and Chloe Kilpatrick are the watchman and nurse, respectively. Rounding out the chorus are Sami Ginoplos, Melia Van Hecke, Marielle Hinrichs and Mary Ziegler.

Sets are by Camp, with costumes by Dominique Green, lighting by Paige Samz and props by Emily Frei. Dramaturgs are Minjoo Kim and Katherine Kopp. Fight choreographer is Dylan McKenna. Movement choreographer is David Marchant. Rob Henke is assistant director. Stage manager is Marisa Daddazio. Original music and percussion are by Henry Claude.

Tickets

Performances of “The Oresteia” will begin at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday, Feb. 24 and 25; and at 2 p.m. Sunday, Feb. 26. Performances will continue the following weekend, at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday, March 3 and 4; and at 2 p.m. Sunday, March 5.

Edison Theatre is located in the Mallinckrodt Student Center, 6465 Forsyth Blvd. Tickets are $20, or $15 for seniors, non-WashU students and WashU faculty and staff. Tickets are free for WashU students. Tickets are available through the Edison Theatre Box Office. For more information, call 314-935-6543 or visit pad.wustl.edu.