Insect-eating plants have fascinated biologists for more than a century, but how plants evolved the ability to capture and consume live prey has largely remained a mystery. Now, scientists at Washington University in St. Louis and the Salk Institute have investigated the molecular basis of plant carnivory and found evidence that it evolved from mechanisms plants use to defend themselves.

The research, published July 11 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), details how calcium molecules move dynamically within cells in the leaves of carnivorous plants in response to touch from live prey. Calcium fluctuation leads to leaf movements for prey capture, likely through an increase in defensive hormone production.

The findings broaden scientists’ understanding of how plants interact with their environments.

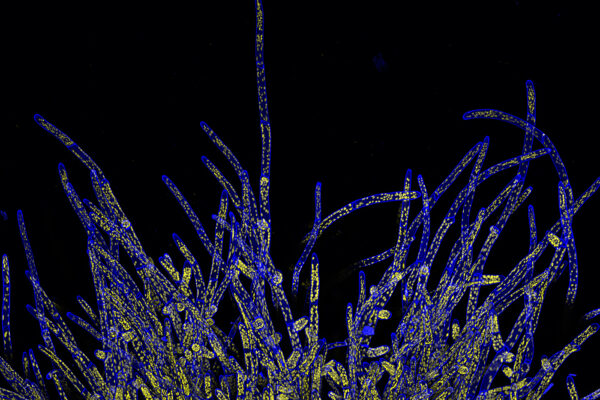

“It was fascinating to see how these plants respond to prey-associated mechanical stimulation, like touch,” said Ivan Radin, co-first author and research scientist in biology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University. “The ability to sense and respond to mechanical forces is something most people don’t associate with plants, especially on this rapid timescale. Our work provides a beautiful visual of this fact.”

Biologists have come to understand that plants such as the spoon-leaved sundew (Drosera spatulata) likely adapted carnivory to survive in nutrient-poor conditions. However, sundews are challenging to grow and their DNA wasn’t sequenced until recently, so scientists had difficulty examining how carnivory works at a cellular level. They were also unsure how carnivorous plants developed prey-capture-associated behaviors, such as leaf movements and digestive enzyme secretion.

For this study, the scientists applied genetic tools to image the dynamic changes of calcium molecules in the leaves as insect prey landed on the leaf and was captured there by sticky secretions. In non-carnivorous plants, calcium signaling plays many vital life-supporting roles, such as triggering the jasmonic acid defense pathway to repel unwanted insect pests.

Jasmonic acid also responds to electrical activity, which is a critical element of prey capture in some carnivorous plants, including sundews. The scientists wanted to know if this same defense pathway of non-carnivorous plants might also be required for the sundew’s carnivorous behavior.

The team found that changes in calcium within the plant cell were required for activation of genes typically targeted by jasmonic acid as the leaf bent inwards, entrapping the insect in digestive juices. The researchers further observed that sundew leaves bent less when they were given non-living prey and when their calcium channels were blocked.

These findings demonstrate that calcium aids in insect prey-capture responses and, together with the work of others, supports the idea that jasmonic acid is involved in insect digestion.

Other authors include Joanne Chory, Carl Procko and Charlotte Hou of the Salk Institute and biologists Ryan Richardson and Elizabeth Haswell of Washington University.

Read more from the Salk Institute.