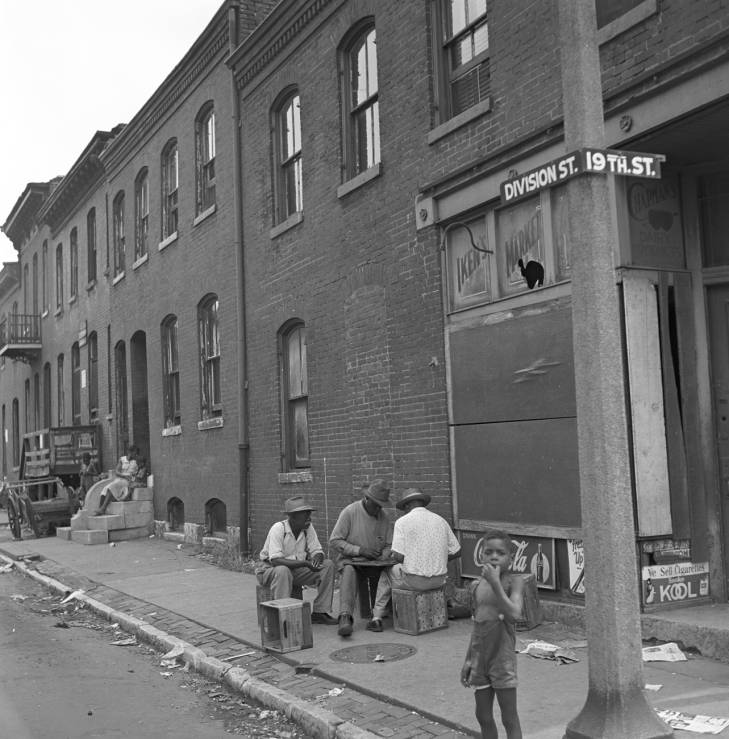

Segregation has shaped St. Louis as surely as the waters of the Mississippi River. Its course can be followed through physical traces, oral histories, fragmented communities and continuing grassroot struggles.

But “what we call ‘segregation’ was hardly inevitable or certain,” write Iver Bernstein and Heidi Kolk of Washington University in St. Louis, in their introduction to “The Material World of Modern Segregation: St. Louis in the Long Era of Ferguson.” Indeed, as an ideological project, the maintenance of segregation “constantly required the beating back and beating down of the alternatives, which were so robust as to frequently threaten to overwhelm it.”

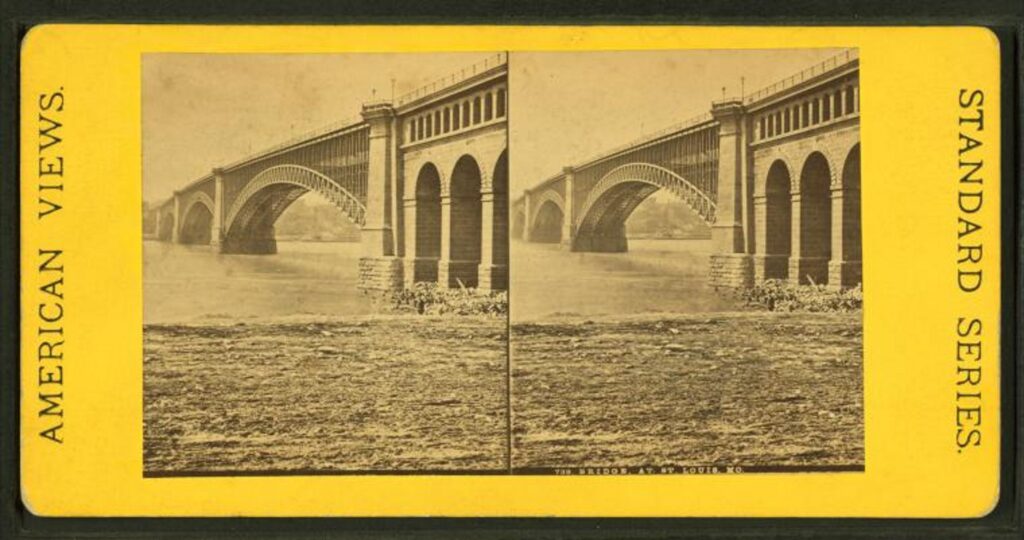

Published as a special issue of The Common Reader, “The Material World of Modern Segregation” collects 17 essays investigating the racial histories of sites throughout the St. Louis region. These range from local landmarks such as the Eads Bridge, Delmar Boulevard and Powell Symphony Hall to lost African American neighborhoods such as DeSoto-Carr, Howard-Evans Place and Mill Creek Valley to the now-relocated Confederate monument in Forest Park.

In this Q&A, Bernstein, professor of history, of African and African American studies, and of American culture studies, all in Arts & Sciences; and Kolk, assistant professor in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, discuss the origins of the book, the ethics of memory work and the tending of community.

Many of these essays grew out of a 2017 conference you organized for WashU’s American Culture Studies program. How would you summarize the aims of this collection?

Bernstein: This book is designed to contribute to our understanding of how St. Louis engages with its past, particularly its traumatic past. One can read these essays, visit these sites and hopefully look at our city with new eyes.

Kolk: In the wake of Michael Brown’s killing, in 2014, it was clear that academic theories of racial experience had reached their explanatory limits, and that the terms of conversation were going to have to change. As a group, we wanted to think very deeply about what it means to write in the post-Ferguson moment, with care for the community whose experiences we’re documenting.

Bernstein: In a way, we’re trying to sort through the wreckage of conventional liberal understandings of segregation — those which insist on soothing notions of “race relations” and “post-race” without engaging the historical and ongoing realities of war and violence, profound rupture and unspeakable wounds.

This involves the hard work of listening — of being humble in the presence of our community.

In all, the book has 18 contributors. How did the group go about selecting locations? Did common themes or approaches emerge during the writing process?

Kolk: Our contributors come from a wide range of disciplinary backgrounds, which was intentional. From the start, we talked about what it means to do site-based work, and together worked to solidify some foundational themes. We wanted to strike a balance between storytelling, site-based exploration and serious historical analysis.

We were very much trying to develop a careful investigative approach — one that starts with noticing a site’s location and material conditions, and includes taking stock of history, local stories and archival materials. It’s almost like assembling a biography of the site, but with a focus on moments of contestation, when the racialized urban experience really comes into view.

Bernstein: It’s often in those eruptive moments that one can clearly see not only traumatic experiences — the moves by political institutions and private developers to contain and segregate — but also the countertendencies, the care and the interdependence that are so often hidden from view.

I think it’s within these countertendencies — what you might call the ethic of democratic love — that one can see the future of our city. And it’s precisely these countertendencies that the segregated landscape seems to obliterate.

Iver, you discuss that ethic of love in your piece on the Wellston streetcar loop pavilion. Though currently vacant, in the years after World War II, it drew as many as 50,000 passengers a day. Why did you focus on that site?

Bernstein: The landscape of segregation can seem naturalized or eternalized, but it was made by a series of decisions. In Wellston, some of these decisions were very specific to the dismantling, in 1966, of St. Louis’ streetcar system. Other decisions, relating to material extraction and rapacious taking by outside forces, are more iterative. That is, they’re constantly being made and remade — for decades.

Today, looking at Wellston’s challenged, tumble-down commercial district, you’d never know that a fierce civil rights struggle played out around the pavilion between roughly 1967 and 1970. For me, one of the revealing moments is a controversy about a racist lawn statue installed by segregationist Mayor Leo J. Hayes.

So often, with monument controversies, the issue is dismissed — either through ignorance or a kind of malignant awareness — as merely symbolic. But the depth of these struggles tells us something about our larger histories, and what we can access by attending to material conditions. The seemingly small but intense controversy over Hayes’ statue, placed in front of Wellston City Hall, was not a symbolic sideshow but a crucial pivot in Black Wellston residents’ historic struggles to access, own and control the material resources they need to survive and thrive — on the “eve” of the creation of the Wellston of today.

If we can answer the question of how St. Louis got to be this way, perhaps we can find the means to undo it.

Kolk: There’s also something really beautiful that comes to the surface in Iver’s piece, and in many of these essays, about that kind of memory work. The simple tending of community — which is invisible to most people — becomes an act of love and resistance.

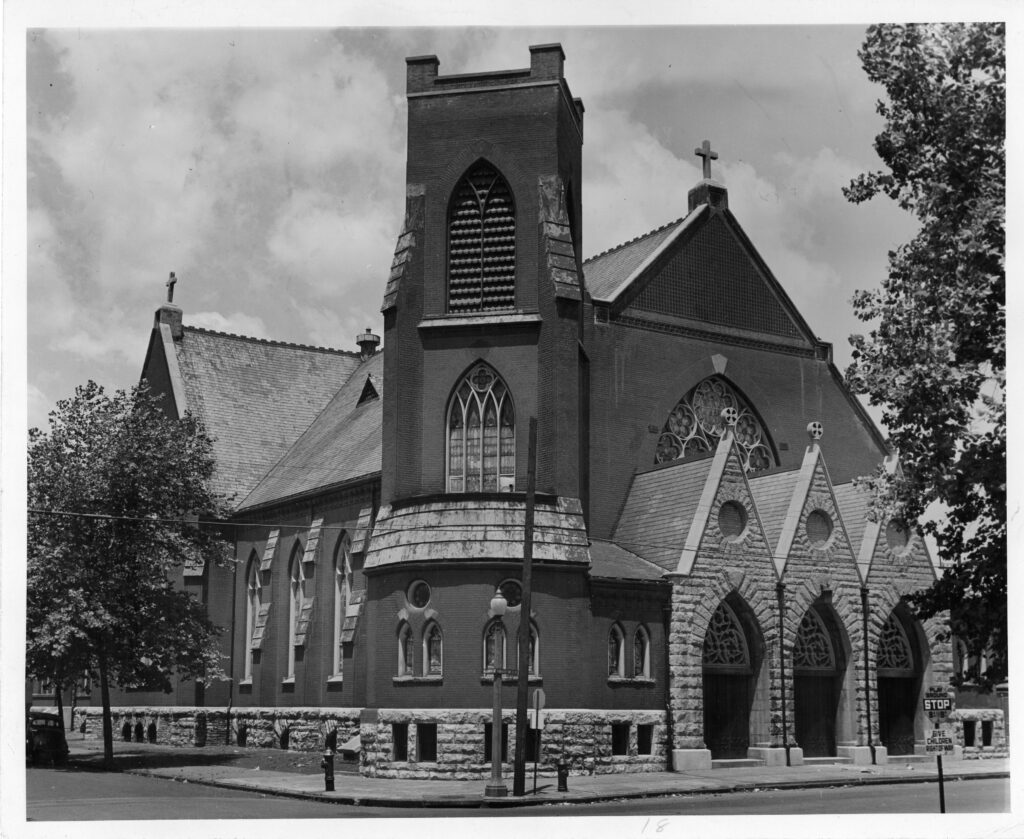

Heidi, your essay about the St. Louis Place neighborhood examines the legacy of St. Leo’s, a long-demolished Catholic church. What does St. Leo’s teach us about the city today?

Kolk: St. Leo’s was the anchor for a diverse working-class community in the heart of the city’s near north side. If you go back to the 1850s, its environs included the Kerry Patch — a squatters’ village first for destitute Irish immigrants — as well as other lower-income neighborhoods occupied by Germans and other immigrant groups, who were eventually replaced by African American laborers who arrived during the Great Migration.

St. Leo’s has been gone for decades, but the community — the inheritors and caretakers of that neighborhood — continued to gather and hold reunions and picnics on the site, which still contained remnants of the church altar and cornerstone. Many of them were second- or third-generation homeowners and inherited property from their parents, who were among the first Black residents of St. Louis Place. And when the city and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency began maneuvering to build a militarized 99-acre compound in the area, it became the site of protests and prayer actions.

I think this points us back to the ways in which these histories are iterative. When you look at previous eras, you can see the reasons why certain neighborhoods took the shapes that they did, spatially and racially. And you can see how those patterns have continued to reproduce themselves.

But the case of St. Louis Place, like other sites that are explored in the collection, is also a story about hope. It’s a story about staying put and committing to the work of community, when everyone else was leaving.

Bernstein: The purpose of engaging these histories is not simply to invoke an alternative ethic of democratic love, but to understand how that ethic addresses the material alienation so many St. Louisans continue to experience and work toward a more just and equitable union.

For more information about “The Material World of Modern Segregation,” visit the project website.

Slideshow

Sponsors and related events

“The Material World of Modern Segregation: St. Louis in the Long Era of Ferguson” is published by The Common Reader: A Journal of the Essay, with generous support from Washington University in St. Louis’ Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity & Equity; American Culture Studies program in Arts & Sciences; College of Arts & Sciences; Brown School; Department of African and African American Studies in Arts & Sciences; Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts; Washington University Libraries; and the Washington University Office of Faculty Affairs and Diversity. The 2017 conference and a related course were supported by a grant from the Washington University Ferguson Academic Seed Fund, the American Culture Studies Modern Segregation program initiative and the American Culture Studies Danforth Endowment.

The Sam Fox School will host a book launch celebration for “The Material World of Modern Segregation” at 4 p.m. Wednesday, April 6, in Weil Hall’s Kuehner Court. Opening remarks will be offered by Carmon Colangelo, the Ralph J. Nagel Dean of the Sam Fox School, and Jason Purnell, associate professor in the Brown School and director of Health Equity Works. Speakers will include Kolk as well as book contributors Jasmine Mahmoud, assistant professor at the University of Washington–Seattle; Patty Heyda, associate professor in the Sam Fox School; and Washington University senior lecturers Michael Allen and John Early.

Washington University Libraries also will host a book discussion at 4:30 p.m. April 27 in Umrath Hall Lounge. Provost Beverly Wendland will provide opening remarks. Speakers will include Bernstein as well as contributors David Cunningham, chair and professor of sociology in Arts & Sciences; Sylvia Sukop, a doctoral student in Germanic Languages and Literatures in Arts & Sciences; and WashU alumnus Josh Aiken, now a law student and doctoral candidate at Yale University.