Every day, anthropologist Crickette Sanz gets a text message or two from a 100-square mile forest preserve National Geographic once called, “The Last Place on Earth.”

The daily contact with the Goualougo Triangle Ape Project, located in a remote preserve in the Republic of Congo in Central Africa, helps Sanz and her team keep track of chimpanzees and western lowland gorillas, who live and interact virtually uninhibited halfway around the world from the Danforth Campus.

“There’s usually a point of contact every morning, about 1:30 or 2:30 a.m.,” says Sanz, professor of biological anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, and co-principal investigator of the project along with her husband, David Morgan. “Typically, we get messages from the field teams to let us know how things are going.

“Just the other day, the research assistants recorded this phenomenal observation of gorillas approaching a tree and wanting to play with the chimpanzees, and a chimpanzee kind of made a swipe at the gorilla,” she says. “The team sends these types of updates all the time, because they know we really want to hear these things.”

Just another start to the day for an anthropologist, one who recently received one of the highest honors an academic researcher can get, fellowship in the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the world’s largest general scientific society. But in addition to monitoring field progress halfway around the world, she’s balancing academic teaching and research with carpools, school lunches and snow days as a wife and mom to two boys, Skye, age 8, and Myles, 4.

As a scientist who has made it her life’s work to study primate sociality, she knows firsthand how important it is to forge strong social connections. “Social networks are key,” she says. “My family, friends, co-workers and neighbors who band together to provide support in various forms have been so important to me, in so many ways.” And they, in turn, have allowed her to make groundbreaking advances in anthropology.

It was research by Sanz, Morgan and collaborators that spurred the Republic of Congo to enlarge the Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park’s boundaries to include the Goualougo Triangle in 2012.

Along the way, Sanz has pioneered the use of camera trapping technology in the study of chimpanzee behavior, improved estimates of ape densities, and conducted long-term monitoring of endangered apes. Her research and outreach efforts also extend to apes in captive settings, such as the Saint Louis Zoo and Save the Chimps sanctuary in Florida.

She recalls with great detail the first time she set eyes on the site as a then-PhD candidate studying anthropology at WashU with the late Robert Sussman, then-professor of anthropology at WashU and a leading scholar on the evolution of human and primate behavior. She remembers that first plane ride landing on a small strip near a remote village adjacent to Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park, and the day’s walk to the project site that had been set up by Morgan. Deep in the forest, surrounded by 600-year-old trees, she was stepping into an area that was already endangered because of logging.

“My first impression,” she says, “was of how vast and magnificent these forests were. Looking out from the small aircraft, just the pilot and I flying from Gabon to the northern Republic of Congo, all I could see was continuous forests.

“Because the area was so remote, the chimpanzees weren’t accustomed to seeing humans. They should have been afraid of us, but they weren’t. They were interested in watching us, and staring at our backpacks and our tripods. They would occasionally throw things at us to see what our reaction would be, and after a while would return to their typical daily activities of foraging, playing, and resting.”

It was unheard of behavior for chimpanzees in the wild. These observations initiated two decades of scholarship into primates, especially the tool-using traditions of chimpanzees and the effects of human disturbance on chimpanzee and gorilla groups co-existing in the same area. The work being accomplished at the site provides insight into the evolutionary history of primates, which, as our closest living relatives, ultimately help us understand our own evolution.

Sanz’ research has expanded to identify factors that influence the spread of information and pathogens among primate communities. This work involves a global network of collaborators who work together to study emerging infectious diseases, quantify anthropogenic impacts, and monitor environmental trends over time. Her work has also become increasingly comparative, involving other species and contexts, which provides research opportunities around the world for WashU students.

Finding balance

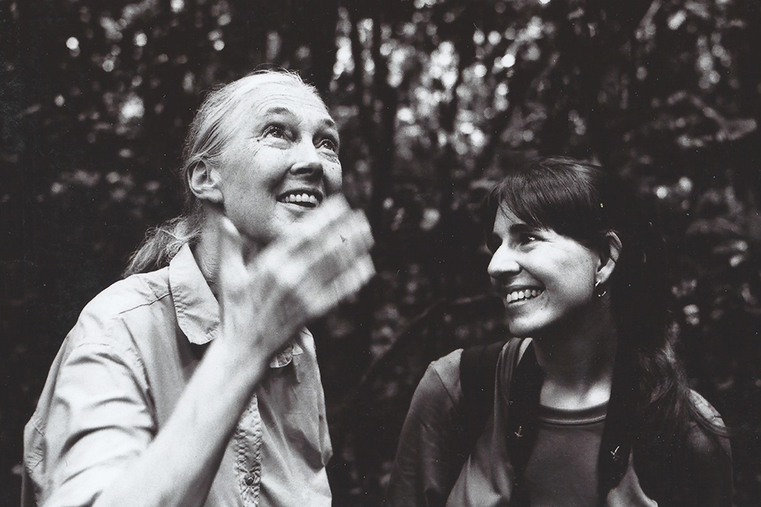

Sanz — who went from being a “studious kid” in a small town in the state of Washington to Washington University in St. Louis to the Congo Basin — acknowledges the scientists who have come before her, including the incomparable Jane Goodall, whom she studied, and then hosted at the Goualougo site in 2003.

“She is a wonderful mentor and friend,” Sanz says. “All of the things you might hope Jane Goodall is, she is. The insights that she shared with us while watching the chimpanzees changed our research forever.”

And now Sanz tries to be a role model herself, paying it forward to future students. “I don’t think there’s anything more rewarding than having your students succeed and reach their dreams,” she says. “When Stephanie Musgrave (assistant professor at the University of Miami), for example, received an offer to join a department, I couldn’t have been more proud!

“We also work very closely with students in Congo. One of our Congolese students was at Oxford and went to the library and looked up the article he had published. He told me, ‘My work is in Oxford!’ It’s wonderful to hear that.”

Even with the AAAS honor, Sanz will not be resting on her academic credentials. “I feel in many ways like it’s just the beginning of my career, there’s so many things still to do,” she says — including another trip to the Congo later this year, where she’ll be relying on that network of hers to keep track of her family.

That, and her own sense of balance. “I can be walking into camp in Congo and feel completely at home, just as I do when I’m at home with my kids,” she says. “The key is to make sure you do whatever it is that makes you feel complete. Some days, it’s a little bit more family and some days, it’s a little bit more work.

“But I couldn’t do any of it without my support networks, and I think about that quite a bit,” she says. “My husband, my sister, my neighbors, colleagues, all being supportive and saying, ‘It’s OK to do this, too.’ ”