Early in her career, Quing Zhu began working on a better way to improve ultrasound imaging for breast cancer patients.

At the time, she was a research assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania with a side interest in the field of biomedical optics, or bio-optics. She used her weekends to attend seminars of a group put together by the late biophysicist Britton Chance, a pioneering researcher in infrared imaging.

“I started to have these ideas of combining ultrasound and bio-optical techniques to come up with a better way to diagnose breast cancer,” she says. “But when you have new ideas and no data, it’s difficult to get a grant.”

But she persisted. Zhu knew intuitively that a dual modality approach to diagnosing breast cancer — ultrasound and bio-optic imaging — could mean better outcomes.

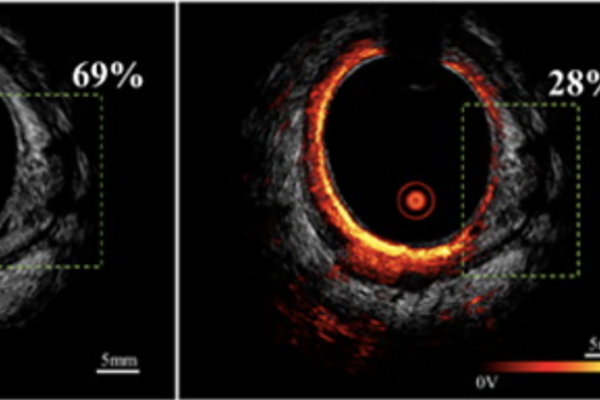

“Each one has an advantage,” says Zhu, the Edwin H. Murty Professor of Engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis. “Ultrasound allows you to see the tumor; bio-optics characterize the tumor blood vessels and tumor oxygen consumption. It reveals the functional information in the tumors.”

It was a good idea that began to get traction, as the two-pronged approach helped not only in diagnosing cancers, but in monitoring and tailoring breast cancer chemotherapy as well.

Later, Zhu began a new approach using ultrasound and another form of bio-optics: photoacoustic technology for better diagnosis of ovarian cancer. By collaborating with physicians at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, both technologies for breast and ovarian cancer have translated to the clinical trials currently conducted at the medical school.

Now, some two decades after attending those weekend seminars in Philadelphia, Zhu is considered a pioneer in combining ultrasound and near infrared (NIR) imaging modalities for clinical diagnosis of breast and ovarian cancers — and for treatment assessment and prediction of outcomes of advanced breast cancers.

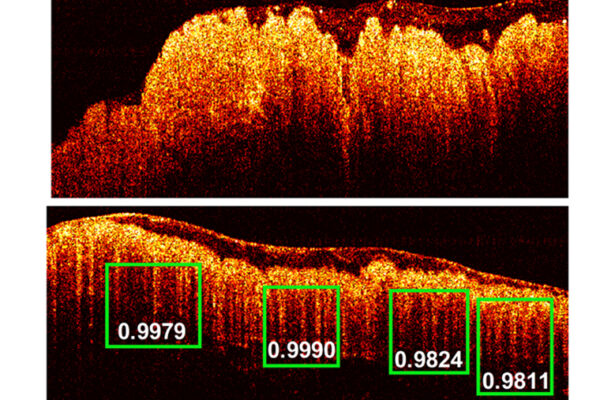

And Zhu, who is also a research member of the Siteman Cancer Center, is not stopping with women’s cancer. Over the past few years, she and her team have been collaborating with surgeons to develop photoacoustic/optical technologies paired with deep-learning neural network algorithms for better assessment of colorectal cancers. Last year, she led a multidisciplinary team that tested an innovative imaging and deep learning technique that was able to differentiate between rectal tissues with residual cancers and those without tumors after chemotherapy and radiation, a procedure that was called a “leap forward” in managing rectal cancer.

Zhu is one of the driving forces behind the recent formation at WashU of the Women’s Health Technologies Initiative, which aims to apply engineering technology to develop new strategies to improve the detection, diagnosis and treatment of conditions affecting the female reproductive system.

“I have been working on breast and ovarian cancer research for two decades,” Zhu says, “and have always had a passion to improve women’s health. My goal is to promote collaboration between clinical and non-clinical researchers and engineers.”

A brilliant career for this unassuming scientist who was once so excited to receive her first research grant that she missed picking up her son, who was 4 at the time, from a school bus stop. “I was so excited to finally get that grant,” she laughs, “that I forgot to pick him up. He took a tour of the bus route. He likes to remind me of that, even now.”

If she has any frustration, it’s the time it takes for technology to get from the research lab to the clinicians. “It does seem to take a lot of time to put into practice,” she says. “I keep telling myself, ‘If I don’t do it, no one knows if it’s working or not.’ So I stay positive.”

And she continues to be on the lookout for developing and implementing new technologies. “Right now, we’re trying to incorporate artificial intelligence into the research, getting more automated and allowing the data to be analyzed automatically, which may lead to faster diagnoses,” Zhu says.

Does she see herself as role model? “It’s all education,” she says. “I teach both women and men who come to my lab that technology can have so many different applications on different cancers. I am just trying to mobilize all possible technologies that I can.”

It’s the kind of work ethic that doesn’t happen overnight.

“Persistence and dedication do payoff,” she says. “And once people know you’re doing good work it’s a lot easier to collaborate. Washington University provides one of the top medical research environments in the country. It allows me to take on many roles.”