From his first day as chancellor at Washington University in St. Louis, Andrew D. Martin made it quite clear how he viewed the “in St. Louis” part of our official name.

“I want to eradicate any kind of perception that St. Louis is merely WashU’s side gig,” he said in his Oct. 3, 2019, inaugural address from Brookings Quadrangle, emphasizing that “In St. Louis, For St. Louis” would be a central initiative of the university from that day forward.

Little did anyone know that it would be a mere matter of months that our being a good citizen of the community was needed more than ever, when COVID-19 became the biggest public health crisis of our time. Washington University resources and research, from the School of Medicine and the Danforth Campus, were called upon not only to cope with the virus, but to help defeat it.

Almost immediately, the university rose to the Herculean challenge and began to innovate, working to better understand the virus, investigate the best ways to detect and fight it, and treat scores of COVID-19 patients from across the St. Louis area. And the university’s efforts to eradicate the virus continue: For example, just last month Matthew Kreuter, the Kahn Family Professor of Public Health at the Brown School, received $1.9 million in federal grants to help increase COVID-19 vaccinations among the Black community in St. Louis City and County.

Key to the grants were community partners, among them the St. Louis City Department of Health, St. Louis County Department of Health, St. Louis COVID-19 Regional Response Team, United Way and Home State Health/Centene, 211, along with the Brown School, the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, and the School of Medicine.

That sounds like a lot of partners, but that’s the key word in WashU’s approach: partnership. The university is looking to become a better partner in a post-pandemic region in myriad ways — crucial not only for WashU’s future but for the entire region.

“This isn’t just about WashU. This is about improving American life in American cities. This is an evolving movement. We are a leader in an evolving and important national trend.”

Henry Webber

“We are now in a world where universities have become economic forces in urban areas,” says Henry S. Webber, executive vice chancellor for civic affairs and strategic planning, who spent 13 years as executive vice chancellor and chief administrative officer before transitioning to his new role this year. He brings with him years of experience and expertise in economic development and community engagement to energize WashU’s role as a regional partner.

“This isn’t just about WashU,” Webber says. “This is about improving American life in American cities. This is an evolving movement. We are a leader in an evolving and important national trend.”

And despite real challenges of a post-pandemic world — huge racial disparities in the region and a regional rate of population growth that is only 40 percent the national level — Webber recognizes that now is the time for Washington University to step up its partnerships and help strengthen the St. Louis region.

To do that, WashU can build on what has been positive for the region, with an eye for always doing more. Here are three examples of collaborations, connections and partnerships in which the university has already shown leadership in the St. Louis region.

Educating the educators

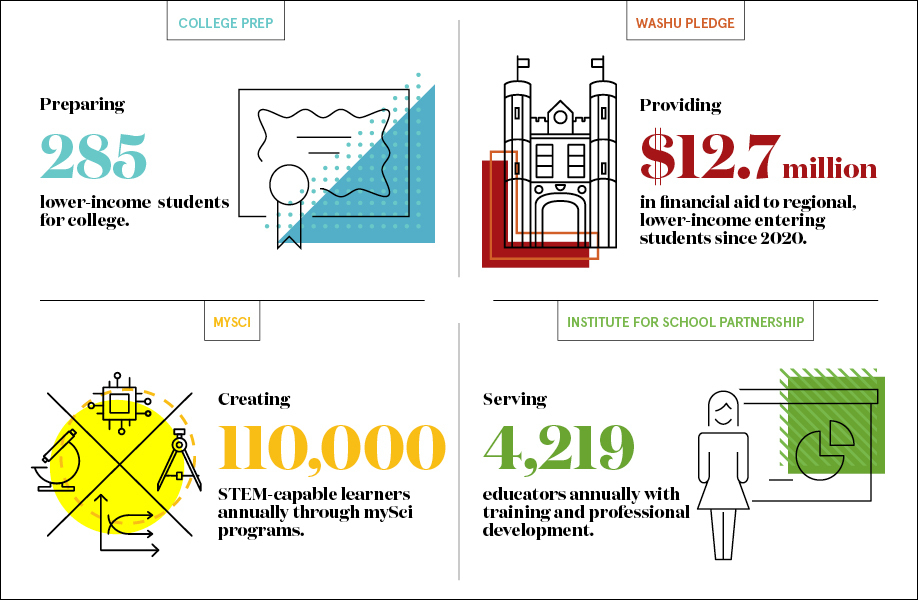

In the late 1980s, Sarah C.R. Elgin, the Viktor Hamburger Distinguished Professor Emerita in Arts & Sciences, founded the Office of Science Outreach, which began as an informal science education partnership with the nearby University City School District. More than three decades later, the Institute for School Partnership (ISP) has grown into a regional hub focused on making STEM education more inclusive and more engaging.

“Our programs are created by and for educators,” says Victoria May, executive director and assistant dean in Arts & Sciences, an educator herself before she joined ISP in 1991. “We ask teachers what they need because we’re continuous learners, too. Our goal is to build partnerships of equals.”

ISP’s educational collaborations run deep, encompassing the majority of school districts, charter schools and independent schools in the region. The partnership goes further with companies and foundations who share the goal of equitable access to a STEM education for every learner.

Among the schools with whom ISP partners is Saint Louis Public Schools, University City and Cardinal Ritter College Prep High School, where the goal is to grow collective leadership by challenging traditional educational models of top-down management and promoting a human-centered organizational approach. Its signature program, the STEM curriculum mySci, is used by public, charter and private schools and serves some 130,000 students. In the school districts of Ritenour, Mehlville and Maplewood-Richmond Heights, ISP is helping educators re-envision math instruction, resulting in better student engagement and achievement.

Other programs of ISP include the St. Louis Teacher Residency program, which helps develop and retain urban educators with a focus on reducing teacher turnover and boosting teacher quality. ISP content specialists teach courses in this targeted Master of Arts in Teaching and Learning program, while teacher-residents work at such schools as Saint Louis Public Schools and KIPP St. Louis, as well as Premier Charter School, City Garden Montessori and Northside Community School.

Washington University’s Office of Government and Community Relations oversees the sponsorship of KIPP St. Louis and Hawthorn Leadership School for Girls, which graduated its first cohort this spring. ISP’s instructional specialists work closely with these charter public schools, providing teacher support, training and resources. ISP also has partnered with local PBS affiliate The Nine Network (KETC/Channel 9) to create and produce on-air math and science classroom lessons through the “Teaching in Room 9” series.

“We did a lot of listening in the summer of 2020, asking teachers to tell us what they needed.”

Rachel Ruggirello

And when COVID-19 upended teaching and learning, ISP used longstanding organizational and district partnerships to support teachers and students, creating resources that enabled educators to pivot to virtual teaching.

“We did a lot of listening in the summer of 2020,” says Rachel Ruggirello, ISP associate director, “asking teachers to tell us what they needed.” By the fall of 2020, ISP had STEM Challenges and partnered with The Little Bit Foundation to distribute STEM materials to the neediest schools through food distribution sites.

No matter how educational instruction evolves after the pandemic and into the future, ISP will continue to build partnerships that create lasting solutions in the region. Early next month, Nikki Doughty joins the ISP team as its first associate director of strategic initiatives. “You need the strengths and talents of everyone to transform the classroom,” Doughty says. “I’m happy to join a team that thinks not only about educating the whole child, but the educator who is supporting the whole child.”

By job and by story

One hallmark of a WashU education is that every student will be known “by name and by story.” As this story illustrates, the region’s third largest employer makes knowing the story a priority for its employees, too.

In 2018, Jessica Cox was a single mother of two working as a home health aide looking to get more training for a higher-paying job. “I loved home health care, and I loved taking care of people,” says Cox, a billing and scheduling associate for the Department of Neurology at Washington University School of Medicine. “But I was still struggling, on Section 8 and food stamps. I needed more.”

She applied for acceptance into a certified medical technician program but was denied funding. That’s when, she recalled, a counselor at the St. Louis County Workforce Development told her, “I have a brand new program that I think you’ll be interested in.”

It was Washington University School of Medicine’s Medical Assistant Apprenticeship, an outgrowth of earlier medical assistant training programs at the med school. For Cox, that meant education tuition-free, covered by grants from the city of St. Louis, St. Louis County, the state of Missouri and the federal government – the first university in Missouri to start such a program. The first cohort, of which Cox was a member, began in the fall of 2018.

What sets this apart from other medical assistant programs is that the participants are hired by Washington University at the same time they are accepted, receiving a salary and benefits. They spend one ½ day in a classroom, then work 4½ days a week in a medical office, working alongside professional staff and doing everything from taking vital signs, updating charts, or as Cox does, scheduling appointments and juggling the curveball of a day-to-day medical office.

“They learn on the job and get the full benefits and support of Washington University,” says Kathy Clark, a consultant in human resources who, along with Tracey Faulkner, lead clinical recruiter in human resources, came up with the idea, and with the support of Legail Chandler, vice chancellor in human resources, ran with it. “We shared our idea with our supervisors and were so excited when they said yes,” Clark says. “And here we are today.”

Since its inception, 81 apprentices have taken advantage of this opportunity, 78 have completed and earned a medical assistant credential and the majority are still employed here.

“It really is the best of WashU,” Clark says. “And because the cohorts are small, we get to know the students, too, many of whom stay in touch.”

Including Cox. “It’s been life-changing for me,” says Cox, noting that not only has the program helped her, but her participation and success have left an impression on her kids, too. “My older daughter noticed me working all day, then coming home and reading textbooks and taking notes. She told me, ‘It’s been great to see you do all that and take care of us on top of it all.’

“The Washington University name holds respect,” Cox says, “and I’ve even found myself wearing my jacket and name tag with pride. I have the utmost respect for this university and the program. I will tell anyone about it.”

From blighted past to bright future

In 2002, a nonprofit was formed to oversee the development of a blighted 200 acres of empty warehouses and crumbling infrastructure, an area that would come to be known as the Cortex Innovation District, “the most successful innovation district in the country,” says Webber, who, in addition to his his duties at WashU serves as chair of Cortex’s board of directors.

From the beginning, Washington University was a major partner, investing $15 million to transform the area into a thriving and vibrant innovation district, partnering with BJC HealthCare, the Missouri Botanical Garden, Saint Louis University, the University of Missouri–St. Louis and the City of St. Louis.

Today, the Cortex Innovation Community is home to 425 companies and has brought more than 6,000 employees and $40.7 million in net new taxes generated for the region. Since its inception, the area has seen new and rehabilitated office space, labs and residential buildings; a public park; retail and restaurants; an investment in public infrastructure, including a new Metrolink station and the first segment of a citywide bike and pedestrian trail, the Brickline Greenway, that will connect it to other parts of the city.

Cortex is a living, breathing example of what can happen when partnerships are put into place and how one district can ignite growth in another and ultimately the entire region. Once completed, the district will contain over 4 million square feet of new and rehabilitated facilities, $2.5 billion of facility investment, 15,000 permanent jobs and over 600 companies.

How has it come this far? Through combining private, local capital and government powers and importing effective partners with the expertise to create and manage spaces appealing to innovators. The Cortex model offers important lessons on how anchor institutions can create economic growth through the building of a dynamic mixed-use innovation district centered on advanced technologies.

In addition to generating jobs and tax revenue, building a diverse, equitable and inclusive environment is an important part of the Cortex mission. For example, in 2019, the district sponsored a 110-person cohort for a free, 20-week coding course sponsored by the national nonprofit Launchcode. Cortex also co-sponsored space for WEPOWER’s Elevate/Elevar, an African American/Hispanic business startup accelerator. Their first cohort includes 10 entrepreneurs from underrepresented St. Louis neighborhoods.

Moving forward

The work of the ISP in the community, a job-training program and the success of a business innovation district are good starts, yet there is more that Washington University does, can — and will — do in the region in the coming months and years. “We’ve got to take this to another level,” Webber says.

“If we are to succeed in our goal to be ‘for’ and ‘with’ St. Louis, it must be a two-way street.”

Henry S. Webber

And one way to do that is to listen, he says, “listening to one another and learning from our shared history as we build on the strong foundation. If we are to succeed in our goal to be ‘for’ and ‘with’ St. Louis, it must be a two-way street,” Webber says.

“We are committed to doing our part, and I am convinced that together we can make a great difference in economic opportunity in St. Louis in the years ahead.”

It’s a challenge but one that Washington University has risen to before. Chancellor Martin says he likes to remind himself of the late Chancellor-emeritus Bill Danforth, who always inspired hope. “Perhaps he put it best,” Martin wrote in the 2020 annual report, “when he once said, ‘I believe that, given the complexities of the times, the university will be needed more than ever.’”

Produced by the Office of Public Affairs

Producer: Kristin Grupas

Creative/Art Direction: Anne Cleary Davis

Writer/Editor: Leslie McCarthy

Editor: Terri Nappier

Graphics: Jennifer Wessler

Video: Javier Ventura