Back when Henlay Foster first enrolled at Washington University in St. Louis, Ethan Shepley was chancellor, Olin Library didn’t exist and the campus had, at long last, racially integrated. That was 1954.

Now, 67 years later, Foster will graduate Friday, May 21, with a degree in music from Arts & Sciences at the age of 84. In the intervening years, Foster traveled the world, played and taught piano, and led one of the federal government’s more important programs in the fight against poverty.

“This degree is not going to help me get another job. It’s not going to help me at all, actually,” Foster said from his home in Rockville, Md., near Washington. “I just want to finish what I started.”

There is no way to know if Foster is the university’s oldest graduate, though it’s safe to say no other student has taken such a journey from WashU first-year to WashU alum.

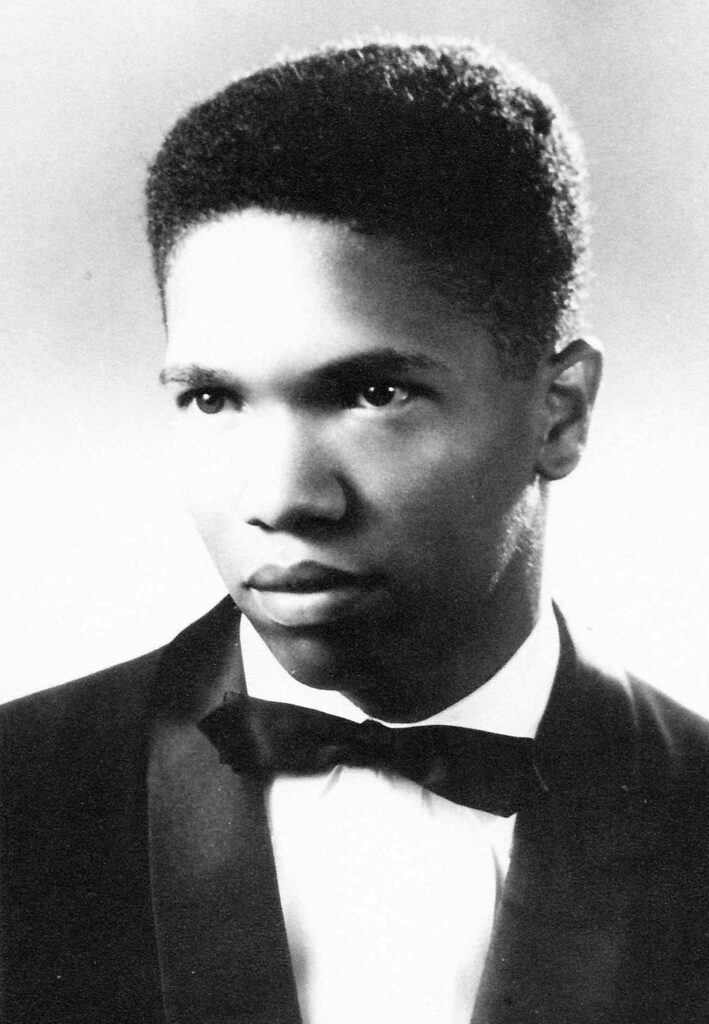

Foster as a young man.

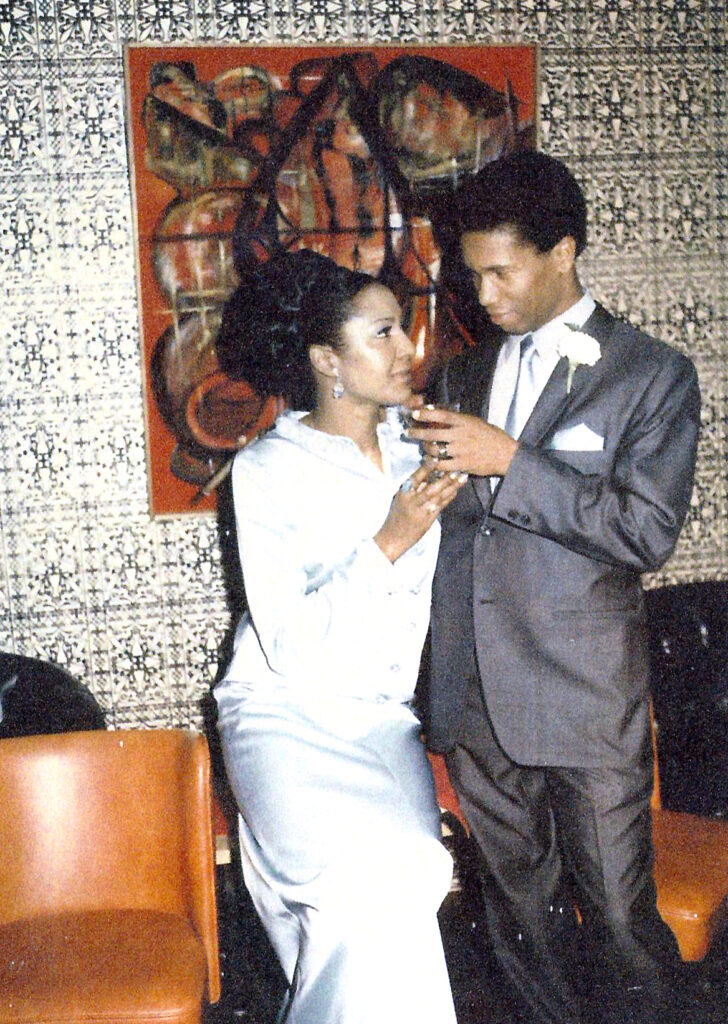

Foster on his wedding day to jazz singer Clea Bradford

Foster, at the piano, accompanying the U.S. Army glee club.

Foster (fifth from right) at a ribbon-cutting for the opening of the Chouteau-Russell Gateway Center

Foster at his desk in Washington D.C.

Foster grew up in Webster Groves, where he attended Douglass High School, a segregated high school in Webster Groves for Black students. He chose Washington University to study classical piano with William Schatzkamer, the famed musician and conductor. Still, Foster worried about how he would be accepted.

“Much to my surprise and my satisfaction, I never encountered one instance of racial prejudice,” recalled Foster, whose sisters Barbara Foster Harlow and Janet Foster Dulaney also studied at Washington University. “Everyone treated me with respect and kindness.”

Foster was only nine credits away from graduating when he enlisted in the U.S. Army. He was, quite simply, tired of school and ready to see the world. Foster requested an assignment in Germany, home to glorious concert halls and opera houses.

“For someone who loved classical music, this was the place to be,” said Foster, who wrote a music column for a paper in Salzburg, Austria, while serving in the Army.

Back home in St. Louis, Foster had neither the time nor the interest in resuming his studies. Foster met and married Clea Bradford, a beautiful jazz singer who performed in Gaslight Square, the legendary entertainment district where Miles Davis and Phyllis Diller performed. He wrote a music column for the St. Louis Argus, one of the oldest Black newspapers in the nation; taught music at the St. Louis Community Music School, now part of Webster University, and performed as an organist at many local churches.

Soon, Foster’s career took a turn. He was offered a job at the St. Louis Human Development Corp., an anti-poverty agency, which led to a position at St. Louis’ Head Start program. After a series of promotions and a move to Washington, Foster was asked to serve as the national director of Head Start, overseeing a budget of nearly $1 billion and some 1,500 community-based organizations. Foster is proud of his role meeting the educational, health and nutritional needs of children from low-income families.

“I have always been concerned about racial relations and the lack of opportunities for these families,” Foster said. “I wanted to help in any way that I could, and I think I have.”

After retiring in 1994, Foster enjoyed playing piano, going to the racetrack and traveling. He did not fret about his unfinished degree.

“And then one day, I said to myself, ‘Why not finish what you started?’” Foster said.

He considered attending nearby University of Maryland or another school in the Washington area. Then the pandemic arrived, and Washington University started moving classes online. He enrolled in two nonfiction classes with Deanna Benjamin, assistant dean and senior lecturer in Arts & Sciences.

“The experience was completely enjoyable, though I had to clean up and put on decent clothes,” Foster said with a laugh. “My instructor, Deanna Benjamin, was terrific, and so were the students. We had a good time and lively discussions. Most importantly, I was treated like a fellow student.”

Benjamin said Foster really came into his own as a writer, deftly marrying journalistic reporting with lyrical prose. She and her students loved to hear Foster’s memories of Washington University and his observations about the changing world.

“After 84 years, he sees things differently,” Benjamin said. “It was really valuable for the students to hear his perspective. And as an instructor, it was a pleasure to listen to his story.”

On Friday, May 21, Foster plans to log on to the university’s website and watch the ceremony. He has no other plans to mark this special occasion, almost seven decades in the making.

“I don’t even celebrate my birthday,” Foster said. “Though maybe I’ll get a good Italian dinner. Other than that, I’ll just be satisfied in my own mind.”