From headwaters near Salem, Missouri, the Meramec River snakes 218 free-flowing miles, through 14 counties and scores of towns, skirting St. Louis before emptying into the mighty Mississippi.

Derek Hoeferlin grew up outside St. Louis, on a wooded hill close to the Meramec. As he commuted to school along Interstate 44, he’d cross the river and its sprawling floodplain twice or more each day.

“It’s always mesmerized me,” Hoeferlin recalls. “Something about its meandering made me daydream. Rivers don’t give a damn about north or south, east or west — or interstates for that matter. Water flows where water wants to flow.”

Today Hoeferlin is a licensed architect and chair of both landscape architecture and urban design programs in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. In many ways, rivers have become his life’s work. But the daydreams are tempered by a growing sense of urgency.

“Architecture is facing a series of very complex global issues. And that’s made me really question my own role. What are the ethics of building near water? What is the ethical response to something like Hurricane Katrina? To the impact of climate change in general?”

— derek hoeferlin

“Too often, architects are responding to emergencies,” he adds. “It’s triage work. But we need to be more proactive. We need to think more holistically across scales and systems.”

The ‘lawless stream’

In North America, no system is larger or more complex than the Mississippi River basin. Measuring more than 1,245,000 square miles, the basin encompasses 31 states and portions of two Canadian provinces. At its center flows the Mississippi itself — the “lawless stream,” in Mark Twain’s famous phrase, that can be neither curbed nor confined.

As a college student, Hoeferlin followed the Mississippi south to New Orleans, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in architecture from Tulane University in 1997. He then spent six years in practice with the New Orleans firm Waggonner & Ball.

“New Orleans is a great place to spend your twenties,” Hoeferlin says fondly. “The city was good to me. Some of my closest friends and most talented collaborators still live and do amazing work there.

“But looking back, other than taking the occasional swamp tour or watching freighters pass by the levees, I never thought much about the city’s relationship with water.”

That changed on Aug. 29, 2005. Hoeferlin had just returned to St. Louis, after earning a post-professional master’s degree from Yale, and joined the Sam Fox School’s College of Architecture and Graduate School of Architecture & Urban Design.

His first faculty meeting took place the morning after Katrina made landfall. Amidst the introductions, levees began to fail in New Orleans. The dread was unbearable. “I didn’t know if my friends were alive or dead,” he says.

Changing course

As recovery from Katrina began, Hoeferlin consulted on water-management projects with Waggonner & Ball. He also joined H3 Studio, Inc., the St. Louis–based practice led by Sam Fox School Professor John Hoal. In 2006, H3 Studio became one of five national firms charged with overseeing the Unified New Orleans Plan.

It was a massive effort. Funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the Clinton-Bush Katrina Fund and the Greater New Orleans Foundation, the plan aimed to develop a comprehensive, citywide rebuilding framework. Hoal, Hoeferlin and numerous Sam Fox School alumni and students spent months documenting conditions, listening to residents, evaluating public priorities and assessing future risks.

Other collaborative water-related planning projects quickly followed, including “Gutter to Gulf” (2008), with Elise Shelley from the University of Toronto and former WashU colleague Jane Wolff; “Rising Tides” (2009), with Ian Caine from the University of Texas; and “Dutch Dialogues” (2010), led by Waggonner & Ball. Hoeferlin also won a 2010 Sam Fox School Creative Activity Research Grant to support field research in the Mekong River delta.

In 2013, Hoal and Hoeferlin joined forces with the Royal Netherlands Embassy in Washington, D.C., for the climate change conference “MISI-ZIIBI: Living with the Great Rivers.” In 2014, led by Hoal, they launched STUDIO MISI-ZIIBI, a yearslong planning initiative that, among other ideas, advocated moving the mouth of the Mississippi, or “head of passes,” 40 miles upriver.

It was (and remains) a radical and contentious proposal. But Hoeferlin points out that the lower Mississippi would have jumped banks and joined the Atchafalaya decades ago if not for the Old River Control Structure, a vast system of locks and dams north of Baton Rouge. Relocating the river’s mouth — from Pilottown to West Pointe à la Hache — would acknowledge the truth of rising oceans while rendering the remaining channel faster, steeper and more resistant to storms.

“The delta today is already an engineered landscape,” Hoeferlin says. “It’s an amazing system, but it’s a 20th-century system. It doesn’t account for climate change, population shift and other variables. And if it fails, the results will be catastrophic.”

A wake-up call

Through it all, Hoeferlin came to three major realizations.

First, though climate change conversations often center on cities like Miami, New York and, of course, New Orleans, the roots of coastal erosion and wetlands loss can start hundreds, if not thousands, of miles upstream.

“Deltas want to grow,” Hoeferlin explains. But their basic building block is rich river sediment. And over the last century, an over-reliance on dams and levees has cut the amount of sediment reaching the coasts by half or more.

“If you radically alter the flow of a river, it will not perform like it did before. Today, the deltas are starving.”

— Derek hoeferlin

Which leads to the second realization: Climate changes are, by definition, changes to vast systems. Managing their effects will require extraordinary coordination. It can’t be done piecemeal.

Third, and perhaps most important, Hoeferlin realized water is not the enemy. “We need water,” he says. “Life and society depend on water. Around the world, delta regions are often the lifeblood of their nations’ economies.”

But too often, we’ve tried to keep water out, rather than to fully understand its place within larger landscapes. As a result, many of our worst water-related disasters — from floods and contaminations to sinking lands and disappearing habitats — are the direct, if unintended, consequences of human activity.

“We have to learn to live with water,” Hoeferlin says, because one way or another, “water always wins.”

Rising seas constrain farmers

At approximately 300,000 square miles, the Mekong River basin is one-quarter the size of the Mississippi basin but contains a roughly equivalent population, around 60 million people. It weaves through six countries and serves as a primary trade route from the Tibetan plateau to the South China Sea.

A generation ago, rice farmers in the Mekong delta’s “nine dragons” region — so named for its nine ocean outlets — could reliably grow three annual harvests, an expectation codified into Vietnam’s “three-rice” agricultural policy. Today, coastal erosion, sand mining, rising sea levels and salt water intrusion are limiting many farmers to a single harvest each year.

“The old systems, the existing frameworks, don’t work anymore,” Hoeferlin says. “But farmers are still beholden to the old policy. So how do you take what had been a water-rich, fresh-water flat and accept the salt? How do you change to a different type of agriculture?”

For many delta farmers, the answer has been to switch from rice to shrimp. “It’s a good example of adaptation,” Hoeferlin says. “But then you have to look at the methods they’re using, and many farmers are raising shrimp in very intensive ways. So we still need to figure out more polyculture approaches, like rotating shrimp with mussels or clams.

“Climate change is not necessarily going to end the world,” Hoeferlin adds. “But it will force us to adapt and do things differently. And for that, you must understand the reality of what’s happening on the ground.”

‘The need for watershed architecture’

In his influential 1995 essay “Bigness or the Problem of Large,” Rem Koolhaas argued that as new technologies increase the scale of architectural projects, architects will necessarily “surrender” to other disciplines. The roles of engineering, manufacturing, construction and politics, Koolhaas foresaw, will be “as critical as the architect’s.”

For Hoeferlin, then a student at Tulane, Koolhaas’ manifesto arrived like a thunderclap. And as New Orleans prepared to mark Katrina’s 15th anniversary in August 2020, Hoeferlin realized Koolhaas’ essay didn’t go far enough.

“I think we have an obligation to the really big scale, to the global scale, to the continental river basin scale. Disciplines shouldn’t worry so much about their own space because there is a bigger space — a literal geographic space — that we all need to share.”

— derek hoeferlin

In his upcoming book, Way Beyond Bigness: The Need for Watershed Architecture (Applied Research + Design, November 2021), Hoeferlin argues that architects, academics, planners, industry professionals and the general public must fundamentally rethink their relationships with water.

“Maybe that sounds like hubris; maybe it’s an impossible problem,” Hoeferlin says. “But it’s important that these conversations begin to happen, and that people begin to find their own places within them. My goal is simply to provide a framework.”

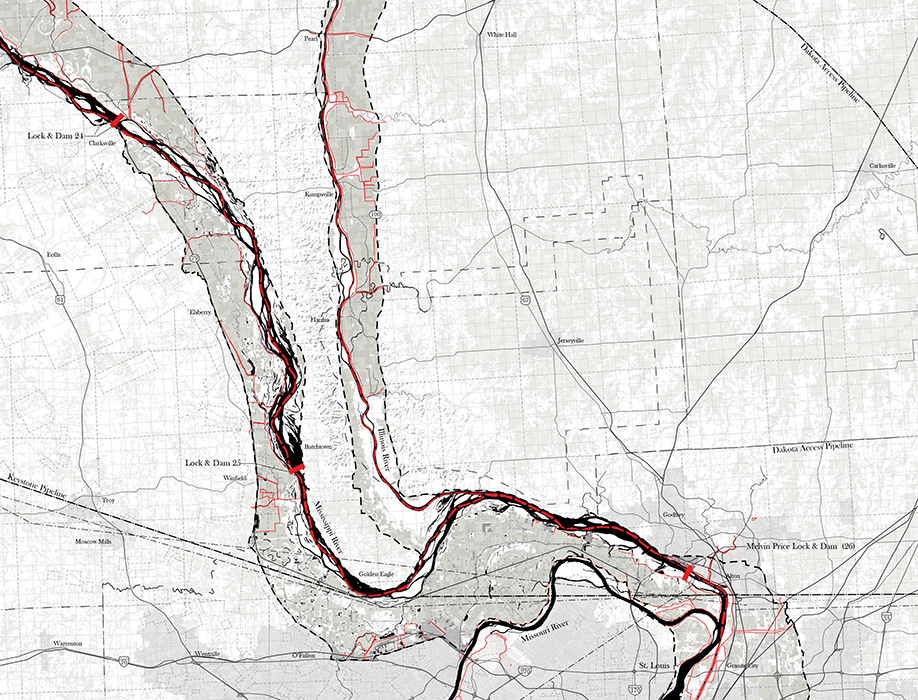

The book’s core is a series of maps, charts, photographs, speculative proposals and other materials relating to the Mississippi, Mekong and Rhine basins. The three basins reflect the last decade of Hoeferlin’s work, but they also reflect three different hydrological scales in three different states of management and development.

“The Mississippi today represents stagnating development,” Hoeferlin explains. Though the river boasts a rich history of infrastructural innovation, it suffers from deferred maintenance and accelerating patterns of severe weather. What’s more, communities along its banks often lack the financial resources and political capital to address contemporary ecological challenges.

In contrast, the Mekong “represents accelerating development,” as China and other nations race to construct concrete mega-dams for hydropower, irrigation and, ostensibly, flood control.

“Unfortunately, these are just 21st-century versions of 20th-century ideas,” Hoeferlin says, with little thought given to impact downstream. “They’ll further reduce sediment flows and generally wreak environmental havoc in the Mekong delta.”

No one solution fits all

Yet Hoeferlin retains a kind of core optimism about even the most daunting design challenges. For a positive example of what he calls “adaptive development,” Hoeferlin points to the Rhine basin, particularly as it reaches the Netherlands and the North Sea.

“The Dutch have centuries of experience when it comes to living with water,” Hoeferlin says. Indeed, more than half the nation’s housing is located in flood-prone areas. But in the age of climate change, the Dutch have realized that building ever-higher dikes is no longer sufficient.

And so, in 2005, the Dutch government launched Room for the River, a massive, $2.85 billion effort to upgrade water infra-structure around the country. For example, in the 2,000-year-old city of Nijmegen, Dutch architects and engineers added a bypass channel to the Waal River, the Rhine’s main distributary branch. This both reduced the risk of flooding in Nijmegen’s historic center and created a new river park on the Waal’s northern bank.

“It’s not that you can’t develop in a floodplain,” Hoeferlin says. “In a way, that’s almost inevitable.” But, he quickly emphasizes, such development must be undertaken responsibly, with an emphasis on environmental ethics and stewardship.

“It’s not about just letting everything go back to nature; it’s about finding ways to lace these different contexts, interest groups and ecologies together.”

— Derek hoeferlin

Still, Hoeferlin warns that the Rhine basin is one-quarter the size of the Mekong basin and 1/17 that of the Mississippi. “The scales are vastly different,” he says. “Addressing issues along the Mississippi and the Mekong won’t be easy, and the solutions may not be the same, but they are achievable through innovative design.”

Back on the Meramec, new levees and big-box construction are further constraining the river of Hoeferlin’s youth. Storms the Meramec could once have absorbed now push it to flood stage and beyond. Nevertheless, Hoeferlin finds a hopeful counter-trend in the adjacent growth of nearby conservation areas such as Castlewood Park, Lone Elk Park and Washington University’s Tyson Research Center — which, though not located in the Meramec floodplain, are part of its larger watershed.

“These places are all within striking distance of the city of St. Louis,” he points out. “I think they offer important clues for the future of coordinated institutional stewardship.

“Optimism is not idealism,” Hoeferlin continues. “It’s actually rather pragmatic. I truly believe that studying deltas, their urbanisms and their much larger river basin contexts will help

us to define the hydro-regions of the 21st and 22nd centuries.

“But we must get the fundamentals right,” Hoeferlin concludes. “And that starts with a basic, foundational understanding of how water shapes our environment.”