It seems impossible that this is the tropics. At 16,000 feet, high above the tree line in the central Andes Mountains, there is snow on the ground. The icy edge of a glacier is wedged between mountains nearby. But there is so much sun here, for so many hours of the day, that the largest high-alpine lake in the Andes never fully freezes.

For much of Peru, like other tropical regions of the world, the difference between summer and winter is a matter of precipitation. There is a rainy season and a dry season. This was supposed to be the dry season.

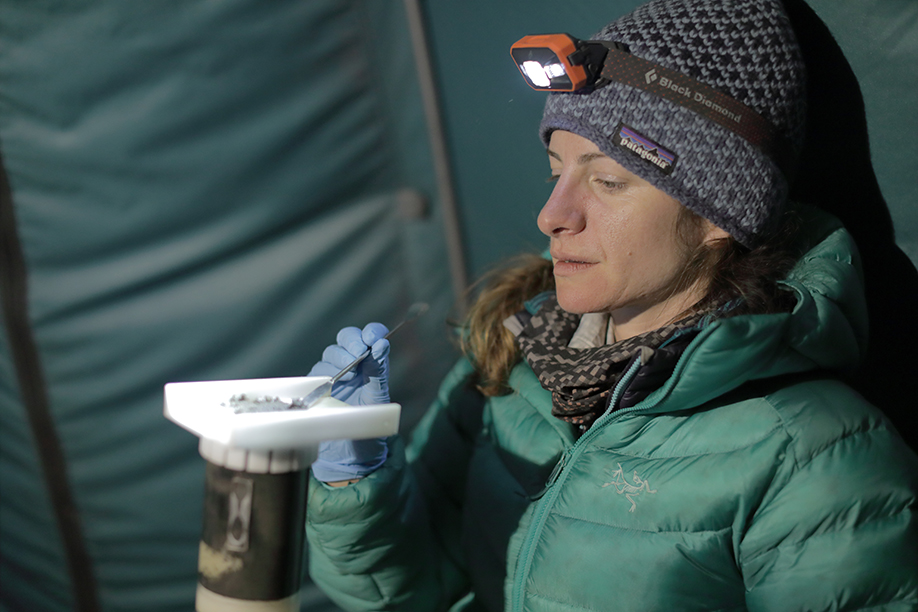

And yet, holed up in her all-weather tent on day four of a planned 14-day field expedition, Washington University climate scientist Bronwen Konecky peered out at another squall

of thundersnow.

No matter. After what it took to get this research team to this field site from Cusco, Konecky was going for it. Today might be the day she finally gets her lake sediment core.

Konecky, assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences, works in tropical regions around the world, gathering evidence of climate change in the geologic past. Using data from rain samples and the muck of dirt, leaves and other organic matter decomposing at the bottom of lakes, Konecky is piecing together a story about the Earth’s climate history — and what it could tell us about our planet’s future.

Her research journey has carried her from St. Louis to Uganda to Indonesia and beyond — but one of the most significant stops is Lake Sibinacocha, in southeastern Peru.

The lake is at the heart of the Cordillera Vilcanota range. It’s part of the Andes Mountains, which run 4,350 miles along the western side of South America — separating a narrow, arid coastal area from the verdant Amazon basin. In fact, the glacier melt that feeds Lake Sibinacocha swirls downhill as a principal water source for the mighty Amazon River.

Glacier runoff is a major source of water for people in the Andes. Water from glaciers fills lakes and rivers, and it also powers hydroelectric dams that keep the lights on. When that water goes away, the future becomes less certain for these high-altitude residents.

Before it feeds the Amazon River, the water from Lake Sibinacocha runs through the Sacred Valley of the Incas — an important agricultural center, as well as a popular cultural destination for some of the 1.5 million tourists who come to the Cusco area to visit Machu Picchu each year, according to 2018 figures.

About 70% of the world’s tropical glaciers, already a rarity, are located in the highlands of Peru. But they are rapidly disappearing. Changes in Peru’s glacier area have been the focus of several research studies; one such study, in the journal The Cryosphere (published Sept. 30, 2019), reported a drastic reduction of almost 30% in the area covered by glaciers between 2000 and 2016.

“Lots of questions still remain about how Andean temperature, snow and rain respond to big changes in the Earth’s climate system,” Konecky says. “We don’t have a lot of data from the Andes. Actually, we don’t have a lot of data from South America, in general. And the farther uphill you move in the mountains, the less and less data we have.”

The nearby Quelccaya ice cap was the largest in the tropics — until recently.

“It is melting, and melting fast.”

— Bronwen konecky

The word “glacier” brings to mind Antarctica, but glaciers are actually found on every continent except Australia. Glaciers are sensitive indicators of changing climate. In the tropics, glaciers typically exist only where mean annual temperatures are close to freezing and where winter precipitation produces significant amounts of snow. If snow accumulates without melting over years, it eventually morphs into glacier ice.

The Peruvian Andes are a dynamic environment of fluctuating glaciers, snowpack, lake levels and ecosystems. Moisture balance on the altiplano — the high plateau of South America — is ultimately driven by water that comes from the tropical oceans via the Amazon basin. Recognizing the global importance of this interconnected system, scientists have been monitoring glaciers in the region, notably the Quelccaya ice cap, for decades. In 1973, a scientific expedition brought back a long column of ice drilled out from its center. At the time, it was the only ice core that had been successfully harvested outside the polar circle.

The results from analyzing Quelccaya ice cores are widely used to reconstruct past climate. But information from ice cores is best ground-truthed against other complementary sources. That’s where Konecky comes in.

“Ice cores can stand on their own,” she says. “But every proxy system has its weaknesses. The best way to leverage the strengths of ice cores, while making up for some of their drawbacks, is to add another proxy system, which is what we’re doing with the lake sediments.”

Sediment — that muck at the bottom of the lake — contains valuable information about climatic and environmental conditions around the watershed when they were deposited. These natural climate archives allow scientists like Konecky to examine climate variability and climate change over the span of decades to hundreds of thousands of years.

“High-quality, instrumental climate records date back only about 150 years,” Konecky says. “Paleoclimate archives help us understand what caused natural climate variability and climate change before that, and how those processes relate to what we’re seeing today. We’re using organic molecules preserved in lake sediments to reconstruct ancient environments and to understand why they changed.”

The Cordillera Vilcanota and the tropical Andes are warming faster than the global average. Warming at extreme altitudes higher than 12,000 feet is expected to amplify with the disappearance of many glaciers by the mid-21st century.

But while scientists believe that human activities have caused much of this warming, they don’t know for sure what comes next. Model projections of the future of the tropics are highly dependent on variables that are still being teased out, such as the relative role of natural climate variability versus external forcing (i.e., human-caused changes) on regional temperature, precipitation and evaporation.

To help make these connections, Konecky reached out to another scientist at the university, Sarah Baitzel, assistant professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences. Together they submitted a proposal for seed funding from Washington University’s International Center for Energy, Environment and Sustainability. Their project is focused on reconstructing past climate and cultural shifts in the Peruvian Andes. The effort is also funded in part by the National Geographic Society.

Recent archaeological findings suggest that humans have been using the land around Lake Sibinacocha from 8,000 to 5,000 years ago through the Inca and early colonial periods about 500 years ago — despite dramatic fluctuations in local climate and lake levels. These changes and their impacts on pre-Hispanic Andean cultures are poorly understood.

“This site, this lake, potentially holds vital information about past climate changes,” Konecky says. “This is something that we can use to help understand what might happen in the future, but also what could have happened in the past and how that could have shaped the way that people were living in the Andes.”

At Washington University, Baitzel teaches courses like “The Incas and Their Ancestors: Archaeology of the Ancient Andes” and “Human Osteology,” an upper-division course in which students learn to identify and analyze human skeletal remains. She also teaches introductory archaeology.

“From an archaeological perspective, highlands are absolutely fascinating environments.”

— Sarah baitzel

“There’s a couple of spots around the world — the Andes, the Himalayas and the Ethiopian Highlands — that people have looked at to see how humans have biologically adapted to living in high-altitude environments.

“But it’s not just a biological adaptation, which, of course, took place a long time ago in the case of the Andean people, at least,” Baitzel says, “It’s the cultural adaptations that intrigue me. There’s a highly specialized way of life that has developed around this type of environment.”

Baitzel has conducted research in Peru for more than 15 years. Today, most of her field work is in Sama, a coastal valley in southern Peru, where she explores social identity formation and interaction among agropastoralists who lived on the geographic margins of expansive Andean civilizations, including the Tiwanaku and Inca.

It was this interest that helped bring Baitzel up the mountain to Lake Sibinacocha. Her husband, Arturo Rivera Infante, a Peruvian native and also an archaeologist, had done previous work in the Cordillera Vilcanota and at the Lake Sibinacocha watershed in particular. The scientists are now collaborating with another Peruvian archaeologist, Martin Polo y la Borda, on work at Lake Sibinacocha.

In 2011, another group of researchers, led by environmental scientist and National Geographic explorer Preston Sowell, discovered archaeological remains under several meters of water on the floor of Lake Sibinacocha. The remains included a rock wall arranged in a zigzag, serpentine pattern, which is thought by some to be sacred architecture. Other artifacts submerged near the wall include intact pots, broken pieces of ceramic materials and arrowheads.

The wall was originally built on dry land and became submerged at a later date. Konecky and Baitzel are still trying to determine exactly when and why that happened. Researchers have also found artifacts on the shoreline, including some that Baitzel believes might be mortuary monuments dating back to Inca or pre-Inca times.

“One thing that draws me to the area is the pastoralism — this very intimate relationship between humans and their domesticated animals — and the complete reliance of one species on the other.”

— Sarah baitzel

“In the case of the Andes, it’s the domesticated camelids — llamas and alpacas — that provide humans with everything from food to wool and fuel,” she says. “Everything that people subsist on here in terms of both food and non-food resources comes from these animals.”

In marginal environments — geographic places where it is already difficult to eke out an existence, like at high-altitude Lake Sibinacocha — climate change has an amplified effect on the way people live, Baitzel says.

“The climate is becoming more extreme,” she says. “In this environment, it means that the freezing episodes are becoming more extreme and more erratic. There used to be very clear seasons. They used to have it almost set to the date when freezing would start to set in at night, and when it would end.

“None of that works anymore,” she says. “Their entire ritual tradition of setting time throughout the year has been upended.”

When unseasonal snow covers the pastures, herders cannot feed their llamas. Some of the animals die. Freezing episodes have also become more extreme. And when rain or snow starts setting in at times when it’s not supposed to, locals can’t cultivate and preserve important food crops for winter in a way they’re used to.

“Over the last thousands of years, local herders have developed a way of living here,”

Baitzel says. “And that way — with the unpredictability of climate change — is no longer sustainable for them.”

Although the environment at Lake Sibinacocha is changing rapidly, there is a stunning abundance of life in the watershed. Scientists have recorded about 70 species of birds in the region, many of which are setting altitude records for their species just by being there. The world’s highest-altitude frog populations are found there, and lizards skitter across the rocks next to the snow. Gangly vicuñas — wild cousins of llamas — teeter on skinny legs along the mountainside ledges. Elusive but still present are the mountain cats — pumas, pampas cats and the extremely rare Andean mountain cat, including one spotted on the Konecky-Baitzel expedition.

It is important to note that this is not a pristine, untraveled wilderness. Lake Sibinacocha and its river valley have been visited by humans — perhaps as a pilgrimage destination, certainly as a place of pasture — long before Europeans or even the Incas took control of the Andean region.

Some of the corrals built hundreds of years ago are still being used for tending llamas by the small group of local families that today live nearby.

“I think our eyes are drawn to the corrals because they are a feature that Western people understand as human-made,” Baitzel says. But the reality could be much more complex. She suspects that the whole landscape has been purposefully modified, mainly to create canals that re-route snowmelt into small “lagunas” and wetlands to support additional food sources for humans and the animals they value.

Lake Sibinacocha is deep and dark — about 10 miles long and 1.5 miles across. Collecting sediment cores from the bottom of the lake was Konecky’s primary goal during her first visit. But it was easier said than done, starting with the process of getting the team and a boat with a heavy motor up to the site, more than 3,000 feet above and a day’s hard travel from Cusco. The final miles of the trek must be covered on foot with help from horses to carry supplies and equipment.

Once at 16,000 feet, after waiting out an unseasonal snowstorm, the scientists called on assistance from a scuba diving team to help them harvest the cores from the shallower reaches of the lake — another extraordinary event, as diving is almost never done at extreme altitudes.

“From the deeper part of the lake, we hope to be able to reconstruct changes in the lake and in the climate and environment over time. From shallower, near-shore parts, we want to potentially reconstruct human presence in the region — particularly with cores taken right next to the archaeological sites.”

— bronwen Konecky

For the most part, Konecky considers her recent expeditions successful. She was able to map the bottom of the lake and determine its maximum depth (almost 300 feet). From slices of the sediment cores that she painstakingly separated and labeled in the freezing conditions on the lakeshore, Konecky and partners at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada, are sifting through and dating the materials that they recovered. Her results will help illuminate how climatic and environmental change served as a backdrop to cultural changes. The contrasts Konecky observes between information from her samples and from the Quelccaya ice cores will help constrain the timing and magnitude of local droughts and precipitation or snowfall relative to broad regional monsoon history and tropical temperature patterns.

Baitzel continues to work with partners in the government agency that oversees archaeological activities in Peru. The samples she collected and registered from Lake Sibinacocha are in safe storage in Lima, waiting to be analyzed after current pandemic conditions abate.

Baitzel is working on a manuscript that includes her initial observations at Lake Sibinacocha, and she is also eager to return to the area to conduct additional field work — targeting other high-altitude sites to the north that connected the remote Sibinacocha valley with more frequently traveled roads between the Inca capital of Cusco and the Amazonian lowlands.

Konecky is also interested in expanding her inquiry to include comparative data from sediment cores that she would like to harvest from other high-altitude lakes in the Andes. But Lake Sibinacocha and its neighboring lakes remain central to her research.

“I’m drawn to this site for a number of reasons, partly for pure climate reconstruction reasons,” Konecky says. “I think it’s an amazing place to be able to learn some fundamental stuff about how the climate system works.

“It’s also a rare opportunity to look at those interactions between people and their environment over such time scales.”