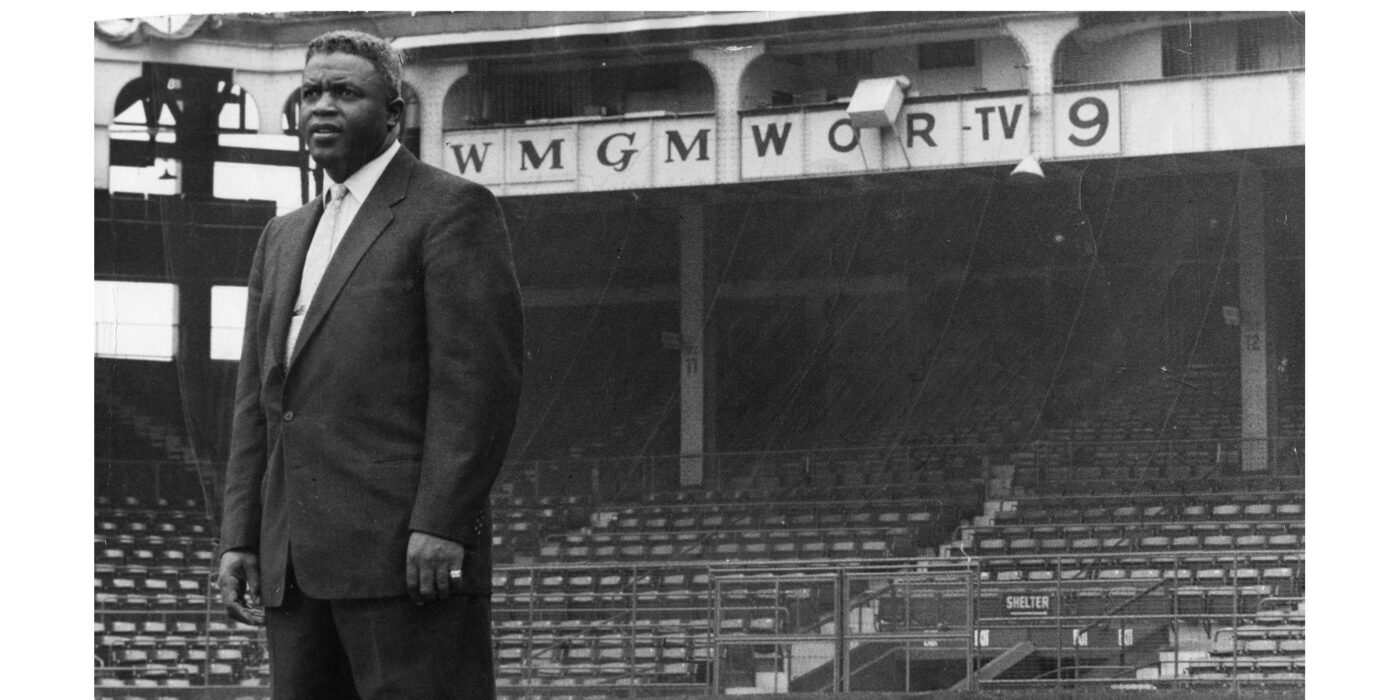

Jackie Robinson’s baseball career is synonymous with civil rights advancement. But his life also illuminates a period of dramatic electoral realignment.

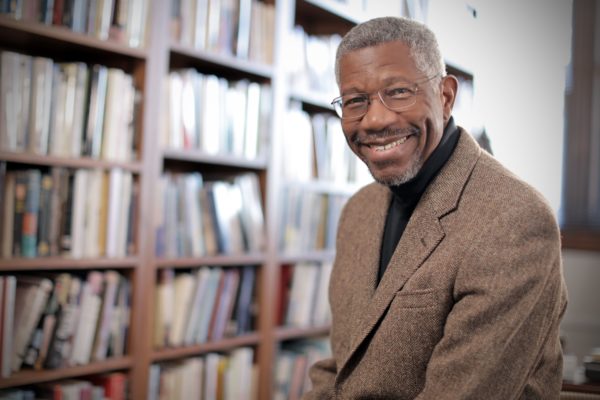

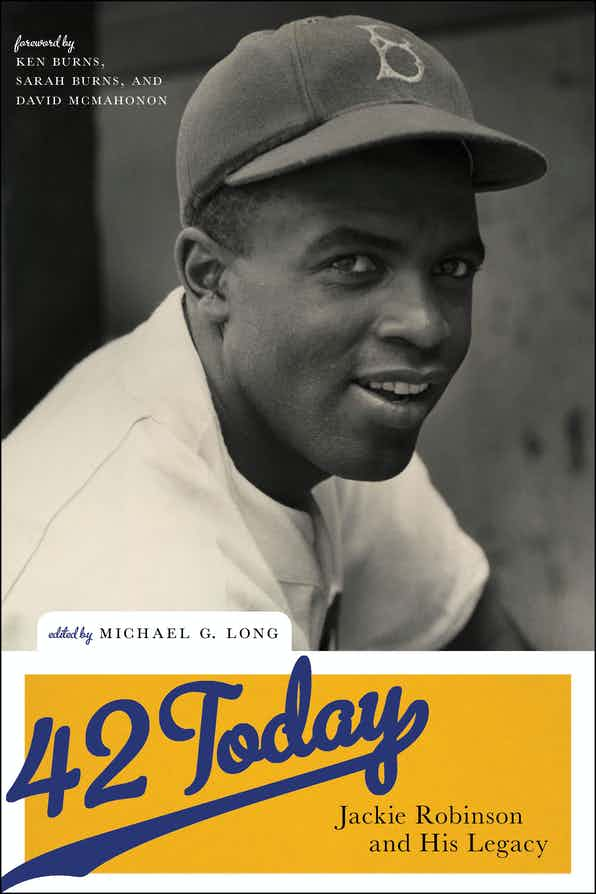

“Jackie Robinson was a Republican,” writes Gerald Early, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters and chair of the Department of African and African-American Studies at Washington University in St. Louis, in “The Dilemma of the Black Republican,” an essay in the new anthology “42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy” (NYU Press, 2021).

“Had he lived his adult life at the turn of the 20th century, this fact would hardly have been surprising or even noteworthy,” Early continues. “For African Americans, the Republican Party was the party of Lincoln, Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner, the Emancipation Proclamation, the radicals who gave us the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Reconstruction Act, the Second Reconstruction Act, the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 and the Civil Rights Act of 1875. It was the only political choice for Black people.”

Nevertheless, in 1972, the year of Robinson’s death, Democrat George McGovern lost the election to Richard Nixon, but won 87% of the Black vote, a percentage that has stayed roughly consistent ever since. The political ground had decisively shifted.

Growing disaffection

Seeds of Black Republican dissatisfaction can be traced to 1877, when then-President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew federal troops from the South, effectively ending Reconstruction. In 1912 — seven years before Robinson’s birth — W.E.B. Du Bois and other activists supported progressive Democrat Woodrow Wilson, though the alliance would not survive Wilson’s notorious racism and re-segregation of the federal workforce.

As late as 1932, Republican Herbert Hoover won a majority of the Black vote. But though Franklin D. Roosevelt “was no great advocate for African Americans,” Early writes, certain New Deal programs — especially those run directly by the federal government, rather than filtered through the states — did help Blacks. More importantly, Black voters “were affected by the idea of an activist federal government and by the idea of massive aid programs.

“All they had to do now was to get the federal government to condition its massive aid with the requirement that no state could practice racial discrimination in administering it,” Early adds. “That lever would break the back of Jim Crow.

A professional endeavor

“Up to this point, it would have been understandable, even predictable,” that Robinson would have been Republican, Early writes. “After this, it becomes a bit more of an enigma, a mystery. After 1932, what was the Republican Party to Black Americans?”

Signs of Robinson’s innate conservatism can be glimpsed in his 1948 Ebony article “What’s Wrong with Negro League Baseball.” Robinson argued that racial oppression and structural disadvantages did not excuse poor management standards. Early notes: “It was similar to the argument that trumpeter Wynton Marsalis and critic Stanley Crouch made about Black music in the 1980s and 1990s: Black music is a professional endeavor that must and indeed does have standards, and anyone who asserts that this view is elitist or that Blacks labor under conditions that make the application of canonical standards unjust or oppressive is ipso facto racist and patronizing.”

As an overachieving, high-performance athlete, Robinson also “had considerable respect for both merit and competition, the two cornerstones of sports and, in some respect, the two values that Black people greatly admired and felt to be defining aspects of their cause for freedom,” Early writes. “Robinson was an example of the new American Negro — fearless in the face of performing with whites as an equal.”

Strategy and ideology

In 1960, Robinson supported Nixon, then vice president to Dwight Eisenhower. “Robinson was favorably disposed to Eisenhower after the federal government protected Black children newly integrating a public high school in Little Rock by sending in federal troops and after the passage of the 1957 Civil Rights Act,” Early points out. And though Nixon later became identified with the “Southern Strategy” of appealing to recalcitrant whites, in 1960, Nixon’s civil rights record was arguably stronger than those of John Kennedy or Kennedy’s running mate, Texas Sen. Lyndon Johnson.

“There was a strategic as well as ideological component to [Robinson’s] affiliation,” Early adds. As an executive with coffee chain Chock full o’Nuts, Robinson (who was accused of being anti-union) “strongly believed that Black people should start businesses and own and manage financial institutions.” The future of the Black community would be “built on the idea of Black economic self-sufficiency.”

Nevertheless, as the decade wore on, Robinson was frequently at odds with his party’s conservative wing. In 1964, he supported Johnson over Barry Goldwater, who’d opposed that year’s Civil Rights Act. In 1968, Robinson broke with Nixon and voted for Democrat Hubert Humphrey.

“He was not a loyal Republican (most Black Republicans during the 1960s found it hard to be loyal to a party that they did not consider to be loyal to them) but rather an embattled warrior, fighting, at times, as most Black Republicans did, to make the party their own,” Early concludes.

“In this respect, Robinson is something of the prototype, the emblem and the icon of the Black people who struggle to be Republican today, to be in a party that does not know how to want them or how to use them in a way that would free them of this dilemma of fighting against themselves to be themselves.”

“42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy” is published by New York University Press. It is edited by Michael G. Long, with forwards by filmmakers Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and

David McMahon.