“Stacking Traumas,” a new site-specific mural by Christine Sun Kim, depicts three large tables, each representing a form of trauma in the lives of Deaf people. Constructed from long parallel lines that resemble sheet music staves, the tables — followed to their end points — are revealed to be extended musical notes. This time-lapse video shows the installation of the mural over the course of two weeks. (Video: Tom Malkowicz/Washington University)

With her spare line and sly, deadpan humor, artist and Deaf activist Christine Sun Kim investigates sound as a physical and social phenomenon while also interrogating the cultural hierarchies in which sound operates.

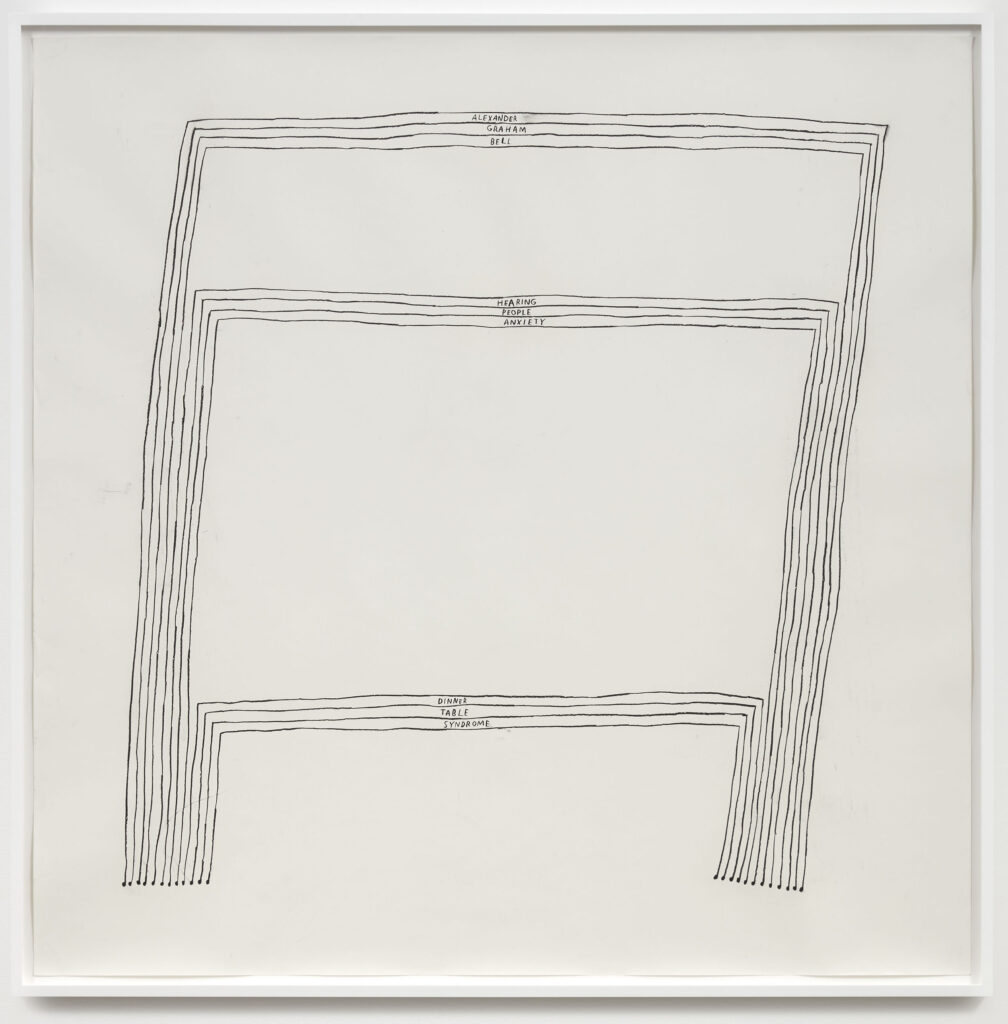

In “Stacking Traumas,” a new site-specific mural for the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University in St. Louis, Kim highlights how the weight of history and everyday experiences intertwine to affect the lives of Deaf people. (Note: Kim prefers to capitalize the word “Deaf” to denote a group with a shared language and culture.)

Installed in the museum’s Saligman Family Atrium, the mural rises 25 feet up the barrel-vaulted wall, arcing, quite literally, over viewers below.

In the following Q&A, Kim discusses the new mural and her overall artistic practice.

You’ve observed that you’ve been “living with sound, and not living with sound, my whole life.” Can you elaborate on that, and how it manifests in your work?

I work with sign language interpreters in order to access education, resources and fellowships. That kind of duality (my voice and theirs) has really shaped my relationship with information and people. Institutions and infrastructures are mostly built on hearing people’s experiences and preferences. Sound and spoken languages have always been part of my reality, whether I like it or not.

My sensors are very much tuned to what kind of sounds create what kind of feedback. Music, for example, has a lot of social status compared to American Sign Language (ASL), so I am tapping into this power potential by using musical notations in drawings as a way to communicate my Deafness, exactly like how I work with interpreters. In that sense, code-switching is probably the biggest part of my practice.

“Stacking Traumas” builds on a recent series of drawings that deal with trauma in the Deaf community. Can you describe the piece?

It’s a stack of three tables or, rather, traumas. These tables are made of musical notes with long stems and bars, and these turn into one big table (or collective trauma). Each table symbolizes a three-word term: Dinner Table Syndrome, Hearing People Anxiety, Alexander Graham Bell. It’s like trauma upon trauma upon trauma.

Bell of course is remembered for inventing the telephone, but he was also an educator who opposed teaching sign language to Deaf children. Is it fair to say that his legacy, represented by the topmost table, continues to exert an influence?

Alexander Graham Bell is probably the biggest source of trauma for the Deaf community in a historical sense. I am therefore very pleased to be given the opportunity to use this particular wall space, since the size and architecture give volume to a specter that looms over Deaf people’s heads, whether you can see it or not.

You’ve noted that, in a culture built for the hearing, being Deaf is inherently political. You’ve also described your focus on “finding a way to be both an artist and an activist.” Are there tensions between those two roles, and if so, how do you navigate them?

Deaf people are forced to navigate and negotiate all the time; in that sense I think that I have always been both an artist and an activist. That very tension is political and multilayered. I might be more of an artist in some situations and more of an activist in others. For the Super Bowl gig, I thought I acted as an activist, but the audiences perceived me as an artist. I guess I am an activist because of my art platform.

One thing I have definitely understood this year more than ever is that communicating through both written words and interpreters is the best way for me to exercise my place and to stay relevant.

Kim performs the national anthem at Super Bowl LIV in Miami on Feb. 2, 2020. (Video: National Association of the Deaf, via YouTube)

About the artist

Born in California in 1980, Christine Sun Kim has exhibited and performed internationally, including at MIT’s List Visual Arts Center (2020); the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2018); the Art Institute of Chicago (2018); the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2017); the De Appel Arts Center, Amsterdam (2017); the Rubin Museum of Art, New York (2017); the Berlin Biennale (2016); the Shanghai Biennale (2016); SoundLive Tokyo (2015, 2013); MoMA PS1, New York (2015) and the Museum of Modern Art, New York (2013).

Kim earned a master’s degree of fine arts in sound and music from Bard College and holds degrees from the Rochester Institute of Technology and the School of Visual Arts, New York. She is the recipient of a Disability Future Fellowship through the Ford Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, MIT Media Lab Fellowship, a TED Senior Fellowship, and she has presented at numerous conferences and symposia. She lives and works in Berlin. Kim is represented by François Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles, and White Space, Beijing.

Exhibition support

Support for the installation is provided by the William T. Kemper Foundation and the Missouri Arts Council, a state agency. The mural was installed by Scott Pondrom. It appears courtesy of the artist; François Ghebaly, Los Angeles; and White Space, Beijing.